Security Risks in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov in 2021

Andrii Klymenko

Tetyana Guchakova

Olha Korbut

The Monitoring Group of BlackSeaNews and the Black Sea Institute of Strategic Studies

1. The Militarization of the Crimean Peninsula and the Black Sea:

The Main Trends of the 8th Year of the Occupation

Since the first days of the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula, there has been no doubt that the main goal of Putin's special operation was to preserve and expand Russia's military base, which was designed to radically change the geopolitical and military-strategic balance in Europe and the Mediterranean.

However, in the first year of the occupation – roughly until mid-2015 – Russia tried to "sell" to the shocked world and its own population a shiny array of ideas as to the non-military but rather tourist, investment, and technological development of its new booty. According to those ideas, Crimea was to become the new Russian showcase that would surpass even Olympic Sochi. And we must say that some people not only in Russia but around the world believed that.

In truth, though, since the very beginning of the occupation of Crimea, the Russian Federation (RF) has been consistently implementing its only target programme – that of the peninsula's military build-up.

A telling marker was that the "Ministry of Crimean Affairs," created two weeks after the illegal annexation, was dissolved as early as July 2015. The following year, in July 2016, the status of occupied Crimea and Sevastopol within Russia was lowered – the Crimean Federal District was eliminated. The so-called "constituent entities of the Russian Federation" – the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol – were included in the Southern Federal District with the administrative centre in Rostov-on-Don. That act established a uniform system for the political and administrative governance and the military command because, since the beginning of the occupation, all Russian military units in Crimea had been part of the Southern Military District with the headquarters in Rostov-on-Don.

The militarization of Crimea has become not only the main content of Russia's Crimean policy but also the main driver of the occupied peninsula's economy. As a result, over the seven years of the occupation, it is the military development of that territory that has become the most striking "success story" of the Russian Federation in Crimea:

-

building up the largest in Europe Russian joint (multi-service) force in Crimea at a rapid pace is underway;

-

since the first days of the occupation, Crimea has been receiving only the newest and cutting-edge military equipment as a matter of priority (in comparison with the military districts of the Russian Federation);

-

all Soviet-time military infrastructure and facilities in Crimea, such as numerous military airfields (around 10), missile launching sites, air defence facilities, radar systems, and nuclear weapons storage facilities, are currently being restored;

-

a new fortified area in the north of Crimea has been created;

-

the construction of new and reconstruction of old military compounds for the deployment of new military units, as well as the construction of housing and related infrastructure for the military is underway; the number of members of armed forces and special services personnel is growing;

-

to fulfil military orders, the operations of the military-industrial enterprises specializing in military instrument-making, shipbuilding, and ship repair have been resumed. These enterprises have been included in the structures of Russian state-owned concerns.

All other areas of life in Crimea – economy, social services, human rights, information space, and national politics – now serve the ideology of a lodgement area.

The military development of Crimea began in the first days of the occupation. On 9 May 2014, the mobile coastal defence missile systems Bal and Bastion-P already took part in the Victory Day military parade in Sevastopol.

In May-June 2014, the mobile surface-to-air missile/anti-ballistic missile system S-400 was deployed near Feodosiia. In November 2014, the first mobile short-range ballistic missile systems Iskander-M appeared in occupied Crimea. Immediately after the occupation of Crimea in 2014, the seized Soviet-time Utes coastal defence missile system was restored and reactivated near Sevastopol.

In 2021, the quantitative and qualitative strengthening of the Russian Black Sea Fleet is reaching its final stage. During the occupation, 13 new missile ships and submarines have been added to the Black Sea Fleet (their missile salvo power is more than 100 cruise missiles), and by the end of 2022, their number will increase to 18.

In addition, six new patrol ships provide for the possibility of installing modular container weapons, including cruise missiles. In August 2020, such modules were already tested. In case of installation of these containers with cruise missiles, the number of new missile ships of the Russian Black Sea Fleet will increase by another 6 units, and their total missile salvo power will reach 192 missiles. These are the same Kalibr cruise missiles that struck targets in Syria in 2015, which sparked concern among the entire Western military-political community. In terms of the range, they are capable of reaching ground targets on the British Isles and in Spain and can carry nuclear warheads.

There is a high probability that since 2015-2016, there have already been nuclear warheads for sea-based and coastal missile systems in Crimea.

As early as March-May 2014, Russian troops took control of and inspected the main Crimean nuclear weapons maintenance facility, previously one of the central USSR nuclear weapons storage bases, the military object Feodosiia-13. In January 2015, a new body was created within the 12th General Directorate of the General Staff of the Russian Ministry of Defence, whose mission is the storage, transportation, and disposal of nuclear units of tactical and ballistic missiles. Back in April 2015, the movement of railroad cars with the Nuclear Danger sign from Rostov-on-Don towards the Crimean Peninsula was recorded. Previously, such cargoes had been seen near the Crimean city of Sudak on numerous occasions.

Reference. The Feodosiia-13 facility in the village of Kyzyltash (Krasnokamianka), in the mountain tract between Sudak and Koktebel, became operational in 1955 and was used to store nuclear ammunition for aviation, artillery, and missiles, including for the warships of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet. The atomic bombs used in the September 1956 tests at the Semipalatinsk range had been assembled at that site. In 1959, the first nuclear warheads in the GDR (Furstenberg) were received from Kyzyltash. In September 1962, on the eve of the Caribbean crisis, six aircraft bombs assembled in Kyzyltash were sent to Cuba. Prior to the occupation of Crimea, the complex of buildings and structures was used as a permanent deployment base of the Special Operations Regiment of the Internal Troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine and the depot of the Ukrainian Naval Forces.

Russia has already completed the transformation of Crimea into a significant military-industrial and service base – the shipbuilding, ship repair, aircraft repair, and missile one.

9 missile ships have already been built or are being completed at the seized Ukrainian plants on the peninsula. Moreover, the construction of two large amphibious assault ships carrying helicopters, UAVs, and vertical take-off and landing aircraft, which have no equivalents in the RF, has begun in Kerch and is scheduled to continue until 2028. The secrecy of this project suggests that the Russian Federation might plan to build something more than helicopter-carrying amphibious assault ships. Most likely, these might be medium aircraft carriers.

Other areas of Crimean specialization, such as repair and maintenance of military aircraft, helicopters, air defence missile systems, and coastal cruise missiles, based not only in Crimea but also in Syria, are narrower in scope but not less important.

During 2014-2021, the military-strategic importance of Crimea for Russia increased sharply, and this process is going on.

The missile capabilities concentrated on the territory of occupied Crimea have led to Russia's absolute military-strategic superiority in the Black Sea region, which radiates into the South Caucasus, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.

Militarized Crimea now threatens not only the entire Black Sea coast but also the whole of Europe, especially on its southern flank.

Since late 2015, occupied Crimea has become one of Russia's main lodgement areas in the Syrian war. The Black Sea Fleet is one of the main participants in the hostilities in Syria: 56 out of 100 sea-launched Kalibr cruise missiles fired by the Russian Navy in Syria belonged to ships of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. In addition to launching cruise missile strikes, the RF supplies the Assad regime and the Russian military bases Tartus and Khmeimim with equipment and ammunition carried by Russian Black Sea Fleet ships from Novorossiysk, occupied Sevastopol and Crimea – the so-called "Syrian Express."

These processes accelerated significantly after the completion of the Kerch Bridge – now equipment and troops can be redeployed very quickly by rail instead of sea ferries through the Kerch Strait, which could be seen in March-April 2021 during the escalation of the military threat to Ukraine in the South and East.

The presence of powerful military capabilities created in Crimea during the years of the occupation has led to the following actions of the Russian Federation, which we can already see:

-

constant military threat of further aggression against Ukraine;

-

the de facto occupation of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov;

-

the obstruction of freedom of merchant shipping;

-

a sharp increase in the number of live-fire naval exercises;

-

a dangerous rise in the number of incidents at sea that could lead to clashes with the use of weapons.

What has become increasingly important since 2018 is not only the developments on the occupied peninsula itself but also how Russia has been using Crimea, which has turned from a global problem into a military threat.

It should be emphasized that no one can reliably predict what scenarios Russia will enact using the military capabilities created on the occupied peninsula.

It is only possible to assert that the Russian Federation has not stopped and will not stop. We can also be certain that both blackmail by war and the actual "hot" war in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov against the coastal regions of Ukraine, as well as Georgia and Moldova, based on Crimea's military power, are completely realistic scenarios, which diplomats and the military should have on the table.

NATO and the EU have realised the international security threats that stem from the militarization of the peninsula and have begun to adjust their plans and actions accordingly. However, to date, a final solution to the problem of adequate deterrence of Russia in the Black Sea has not been found.

2. The Situation in the Sea of Azov

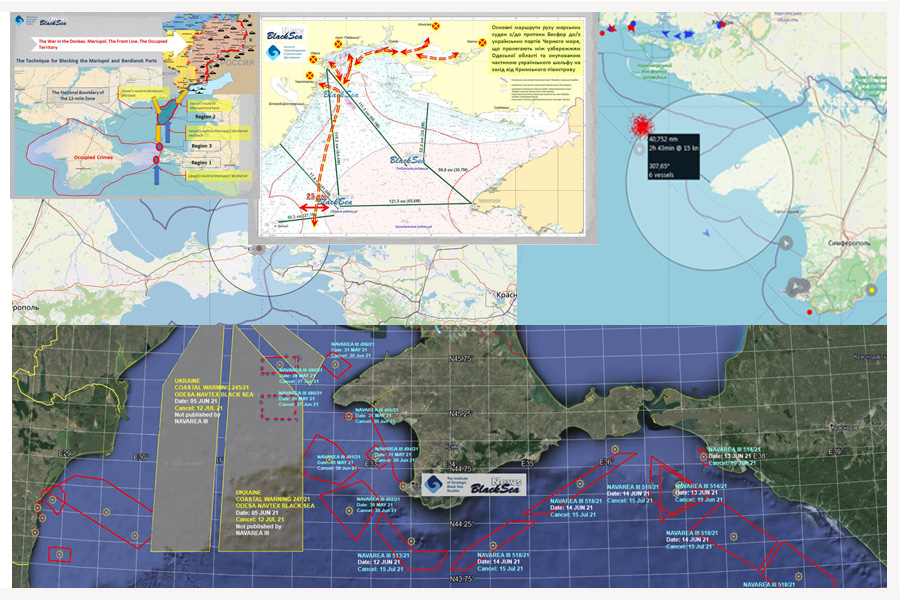

2.1. The Kerch Strait, the Situation with Arbitrary Delays of Merchant Ships

Bound for/from Ukrainian Ports on the Sea of Azov by the Coast Guard of the Russian Border Service of the FSB

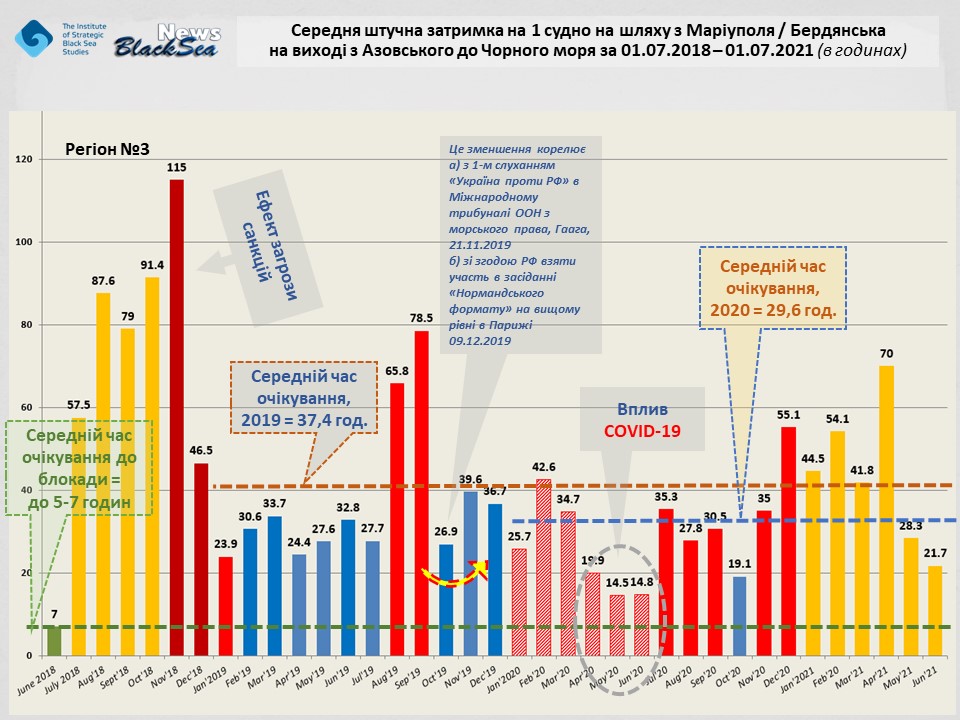

In November 2020 – April 2021, there was a significant increase in the duration of arbitrary delays of ships at the exit from the Sea of Azov (i.e. those carrying Ukrainian export cargoes, mainly to the EU, Turkey, and North Africa).

This figure for 6 months was higher than the average for 2020, i.e. over 29.6 hours per vessel, namely in November 2020 – 35 hours; in December 2020 – 55.1; in January 2021 – 44.5; in February 2021 – 54.1; in March 2021 – 41.8; in April 2021 – 70 hours on average per vessel.

Reference. Prior to the beginning of the de facto blockade of Ukrainian ports in May 2018, the average wait time for permission to pass through the Kerch Strait had been 5-7 hours. In the second half of 2018, this figure reached 80-115 hours. The situation was later eased due to political and diplomatic pressure on Russia from Western countries.

Back then, this obstruction of traffic was already considered in the context of Russia's demands concerning other issues, such as exploring the possibility of resuming the supply of Dnieper water to occupied Crimea.

The decrease in the duration of arbitrary delays of vessels in the Kerch Strait from December 2018 was due to the imminent threat of the introduction of the "Azov package" of international sanctions against Russian ports on the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. In addition, this reduction resulted from linking the Azov problem to the EU's decision on permits to continue the construction of the Nord Stream-2 gas pipeline. We even called this decrease the "Merkel-Macron coefficient."

In 2019, the average duration of arbitrary delays per vessel was 37.4 hours.

In 2020, this figure was 29.6 hours. This decrease resulted from Russian border guards of the FSB Coast Guard’s fear of contracting COVID-19, as up to half of the vessels subject to inspections were going from ports of Italy and other European countries, where, in the spring of 2020, a significant outbreak of the pandemic occurred.

In November 2020 – April 2021, there was a significant increase in the duration of arbitrary delays – up to an average of 53 hours.

The maximum average duration of arbitrary delays of ships leaving the Sea of Azov in 2021 was observed in April – 70 hours. The highest rates of delays of individual vessels at the exit from the Sea of Azov (compared to the wait time at the entrance to the Sea of Azov) were observed in the first half of April 2021, when they amounted to 220 hours, i.e. almost 10 days.

This coincided with the transfer of a significant number of Russian troops and equipment – including a group of 15 warships of the Caspian flotilla across the Sea of Azov – to occupied Crimea during the spring military escalation.

Later, in May – June 2021, these indicators returned to the average values of the previous year: more than 20 hours.

This was due to the seasonal increase in Russian marine grain exports through transshipment in the Kerch Strait. During this period, a large number of merchant ships, carrying grain from Russian regions on the river Volga through the Sea of Azov and transshipping it in the Kerch Strait to large foreign vessels, accumulated in the Kerch Strait. Therefore, arbitrary delays of a large number of Mariupol and Berdiansk-bound vessels in the Kerch Strait would hinder the transshipment of Russian grain.

On average, about 60-70 vessels enter/leave the Ukrainian ports on the Sea of Azov every month. About 50% of them are related to the EU in one way or another (flag, shipowner, port of destination, or a combination of such features).

They account for 5-7% of Ukraine's exports (mainly metal and grain). The number of vessels passing through the Kerch Strait to/from Russian ports on the Sea of Azov, the Don, and the Volga is measured in hundreds per month. This river-sea route is used by the Russian Federation for very significant grain exports (in this sense, when Russia forces the vessels carrying Ukrainian grain cargoes to wait, it also creates obstacles for a competitor in the world grain market). In addition, it is one of the main routes of maritime exports of Russian oil products through transshipment in the Kerch Strait.

Reference. Prolonged inspections in the Kerch Strait of merchant ships going to/from Ukrainian ports on the Sea of Azov (Mariupol, Berdiansk) were initiated by the Coast Guard of the FSB Border Service in May-June 2018 – after the commissioning of the Kerch Bridge. The pretext for such inspections is the possible presence aboard ships leaving the Ukrainian ports of sabotage groups and explosives to destroy the Kerch Bridge (V. Putin’s pet project). This, incidentally, explains the fact that ships bound for the Ukrainian ports on the Sea of Azov are delayed in the Kerch Strait for a shorter time than those leaving the Ukrainian ports. For example, in March 2021, the average duration of arbitrary delays by Russia of ships bound for Mariupol or Berdiansk was 14.3 hours and on the way back – 41.8 hours.

From May to October 2018, we also recorded delays of commercial vessels going to/from Mariupol and Berdiansk on the move by ships and boats of the Coast Guard of the FSB Border Service for "security checks." There were a total of 110 such delays at sea, including 56 delays of vessels related to EU countries. A significant part of such delays took place only 5-7 miles from the port of Mariupol.

These delays at sea ended in October 2018.

The reason why these delays on the move stopped was the following two factors.

-

The first was the fact that 2 small armoured gun boats of the Ukrainian Navy (Project 58155, Gyurza-M class) appeared in the Sea of Azov and began patrolling the Kerch Strait – Berdiansk – Mariupol route. At the end of October 2018, there were 2 incidents when Ukrainian boats prevented the boats of the Coast Guard of the FSB of the Russian Federation from stopping commercial vessels (including the warning of the use of weapons);

-

The second factor was political and diplomatic pressure on Russia from Western countries and extensive coverage of these events in the Western media.

2.2 An Incident in the Sea of Azov Involving Gun Boats of the Ukrainian Navy

and Boats and a Ship of the Coast Guard of the FSB RF on 14-15 April 2021

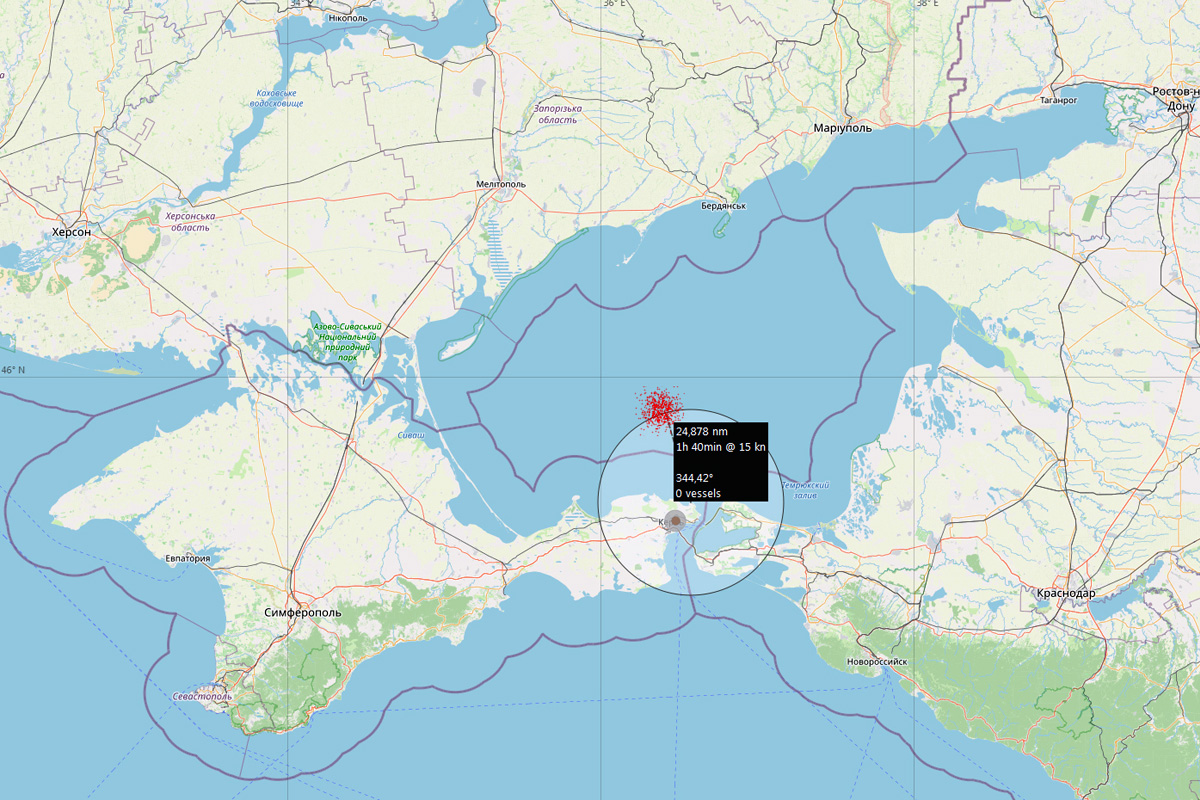

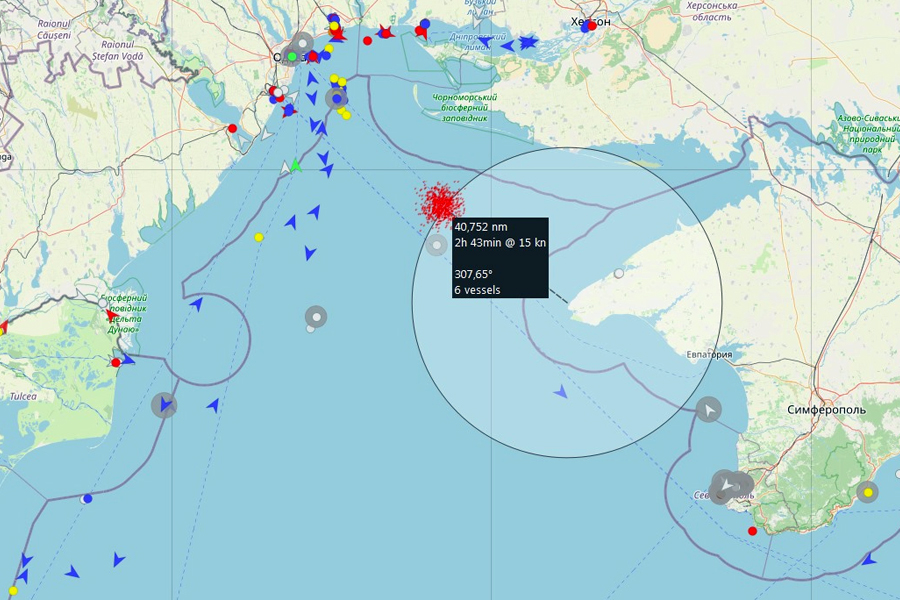

The incident in the Sea of Azov involving 3 small armoured gun boats (Gyurza-M class) of the Ukrainian Navy and 5 boats and a ship of the Coast Guard of the Border Service of the FSB of the Russian Federation with call sign No. 734 happened on the night of 14 to 15 April 2021.

Sources of the BlaskSeaNews Monitoring Group reported from the Sea of Azov: "The night was hot. At least 5 FSB boats carried out coordinated provocative manoeuvres against the 3 Ukrainian small armoured gun boats. Commands were given by the coast guard ship of the Russian Federation No. 734. In the morning, the Ukrainian boats returned to Mariupol."

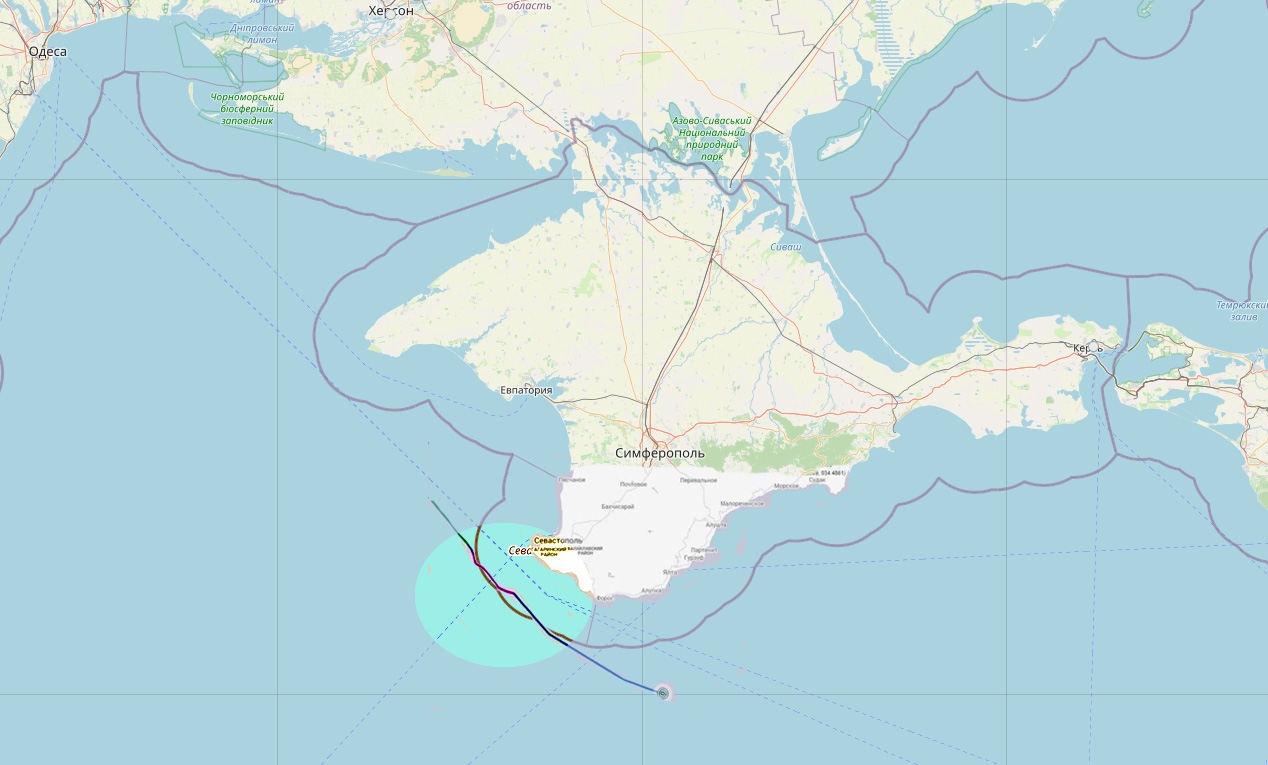

According to our sources, at night, in response to threats from the Russian ship, Ukrainian sailors had to warn about their readiness to use weapons. The incident happened 25 miles from the Kerch Strait (See Figure 3). The Ukrainian boats, as usual, were patrolling the route between the Kerch Strait and Ukrainian ports and escorting commercial vessels.

Note that on 14 April 2021, the Monitoring Group recorded that the naval force of Russia’s Caspian Flotilla, including 8 Serna-class landing craft and 3 Shmel-class gunboats, accompanied by 2 hydrographic vessels, left the Taganrog Bay of the Sea of Azov, bound for Kerch (Course 201), around 17:00 at the speed of 7 knots. They were scheduled to be in the Kerch area at approximately 3-4 a.m. on 15 April 2021.

That is, the attempt to force the Ukrainian Navy's boats to veer off course was made in order to prevent them from approaching the Caspian Flotilla boats bound for Crimea.

2.3. An Incident in the Sea of Azov Involving Gun Boats of the Ukrainian Navy

and Boats and a Ship of the Coast Guard of the FSB RF on 22 May 2021

At the beginning of the 3rd decade of May 2021, the Ukrainian Navy in cooperation with the Sea Guard were conducting tactical exercises in the Sea of Azov.

In total, up to ten boats of the Navy and the Sea Guard of Ukraine were involved in the exercises in the Sea of Azov, including two Gyurza-M-class gun boats of the Navy – Vyshhorod and Akerman. The skills that were practised during the exercises included conducting search-and-rescue operations, covering the landing of the assault group from a helicopter at sea, and sea battle with enemy ships.

The area designated for combat training was closed to shipping, of which the Russian side had been warned in advance by the Ukrainian Navy. However, the Russian vessels deliberately ignored this warning.

3 ships of the Coast Guard of the FSB of the Russian Federation tried to interfere with the exercises of Ukrainian sailors. One of the Russian ships went straight to the course of the Ukrainian Navy boats, trying to force them to manoeuvre and deviate from the course and ignoring all the warnings of the boat commander.

However, later, seeing that Ukrainian gun boats were rapidly approaching, the Russian ship’s crew made contact and said that they understood the warning and would comply with the requirement to leave the training area.

3. The Situation in the Black Sea

3.1. The Build-Up of the Russian Naval Force in the Black Sea

During the Military Escalation in March-April 2021

At the end of March 2021, Russia concentrated a huge number of troops, including those from the Navy, along the Ukrainian-Russian border in Bryansk, Voronezh, and Rostov Oblasts of the Russian Federation and on the occupied territories of the Donbas and Crimea in preparation for the Zapad 2021 exercises scheduled to be held in September.

At that time, Russia gathered in the Black Sea almost all ships of the Black Sea Fleet, reducing the number of warships traditionally stationed in Syria and off the coast of Syria as part of the Mediterranean Squadron of the Russian Navy. Usually, 5-7 warships of the Russian Federation (excluding submarines and auxiliary vessels) are present in the Mediterranean Sea on a rotation basis. However, in mid-April 2021, there were only 2 warships left.

On 15 April 2021, a group of 15 ships of the Caspian Flotilla arrived in the Crimean Peninsula through the Volga-Don Canal and the Sea of Azov, including

8 high-speed landing craft: 6 Serna-class vessels of Project 11770, reaching a speed of up to 30 knots and having a landing capacity of one main battle tank or 2 armoured personnel carriers and 92 members of an assault-landing force; one vessel of Project 1176 (codenamed Akula, the Ondatra class according to NATO classification ) with a landing capacity of one main battle tank or 2 armoured personnel carriers and 92 members of an assault-landing force; and one Dyugon-class landing craft of Project 21820 with a landing capacity of 2 main battle tanks or 4 armoured infantry fighting vehicles/armoured personnel carriers and 90 members of an assault-landing force;

3 Shmel-class river gunboats of Project 1204, 3 tugs, and a hydrographic vessel.

This flotilla participated in the exercises of the Black Sea Fleet and then was in the Kerch Strait.

On 17 April 2021, in the midst of the Russian escalation, 4 major amphibious assault ships of other Russian fleets entered the Black Sea in one day:

two ships – from the Northern Fleet, (031) Aleksandr Otrakovskiy and (027) Kondopoga, and another two – from the Baltic Fleet: (130) Korolev and (102) Kaliningrad.

They took part in embarkation and landing exercises at the Opuk training area and range near Feodosiia in occupied Crimea.

That is, from 17 April 2021, there were 11 major amphibious assault ships in the Black Sea (7 – of the Black Sea Fleet, 2 – of the Baltic Fleet, and 2 – of the Northern Fleet).

They included 3 Project 1171 Tapir-class amphibious assault ships (NATO reporting name: Alligator). Each such ship can accommodate up to 20 main battle tanks or 45 armoured personnel carriers, or 50 lorries and 300-400 landing troops.

The remaining 8 major amphibious assault ships were of Project 775 (NATO reporting name: the Ropucha class). The landing capacity of each such ship is 10 medium tanks or 12 armoured personnel carriers and 340 people.

The concentration of such a group of amphibious ships (which can take on board several battalions of landing troops with equipment) indicated the possibility of large landing operations on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine.

8 landing craft of the Caspian Flotilla left Kerch for the Caspian Sea only on 6-7 July 2021. During the same period – 7-11 July 2021 – amphibious assault ships of the Baltic and Northern Fleets left the Black Sea. However, 3 gun boats and 2 auxiliary vessels remained in the Sea of Azov.

3.2. The "War of Exercises" Before Sea Breeze-2021

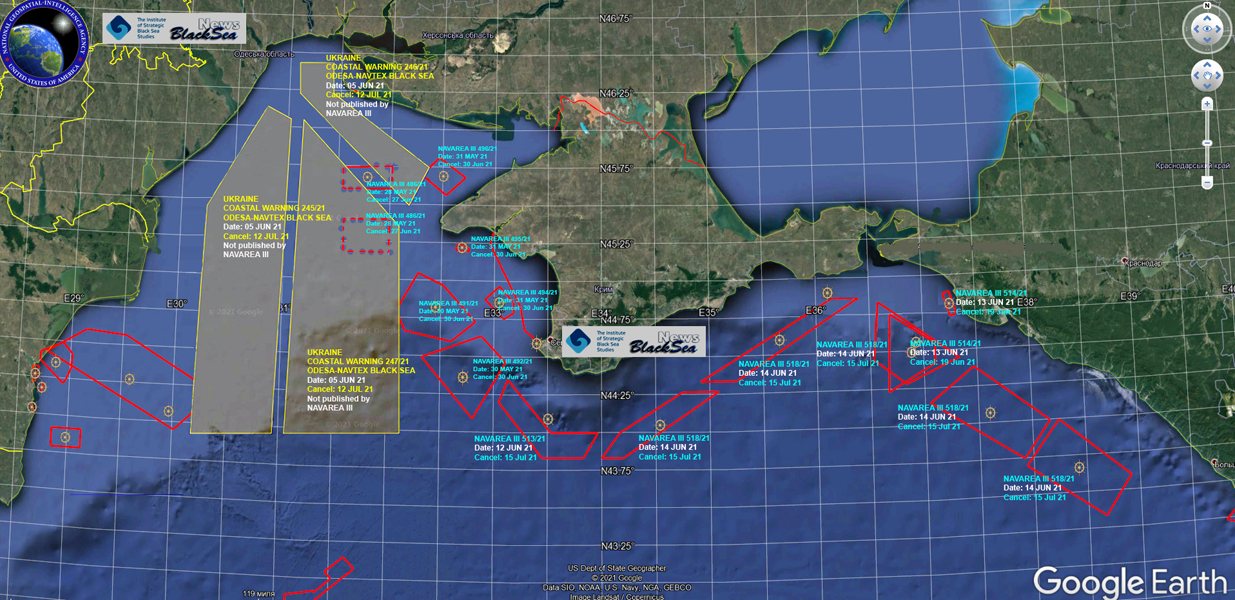

In the summer of 2021 – for the second year in a row – there was a situation where the Ukrainian Navy, in simple language, "reserved" the Black Sea areas in advance for conducting the international exercises Sea Breeze-21*. Also, for the second year in a row, the Spanish Hydrographic Institute, which is responsible for publishing warnings about the closure of Black Sea areas for shipping, stubbornly "couldn’t see" the notifications from the Ukrainian Navy **. Meanwhile, the Institute published warnings from the Russian Black Sea Fleet, which were issued much later.

As a result, the situations arise where enemy states conduct naval exercises in the same areas.

*Sea Breeze-2021 was carried out from 28 June to 10 July 2021.

**The history of the war of exercises in previous years is described here: The "War of Exercises" in the Black Sea: A New Very Dangerous Stage that Cannot Be Ignored: «Війна навчань» в Чорному морі: новий дуже небезпечний етап, про який не можна мовчати

It is worth reminding that closure of sea areas is carried out by transmitting NAVTEX messages. NAVTEX (NAVigational TEleX) is an international automated notification system. Its technical implementation is telex. In navigation, it is used for delivery of navigational and meteorological warnings and forecasts, as well as urgent maritime safety information (MSI), to ships. It is a component of the International Maritime Organization Worldwide Navigation Global Maritime Distress Safety System (GMDSS) in accordance with SOLAS-74/88.

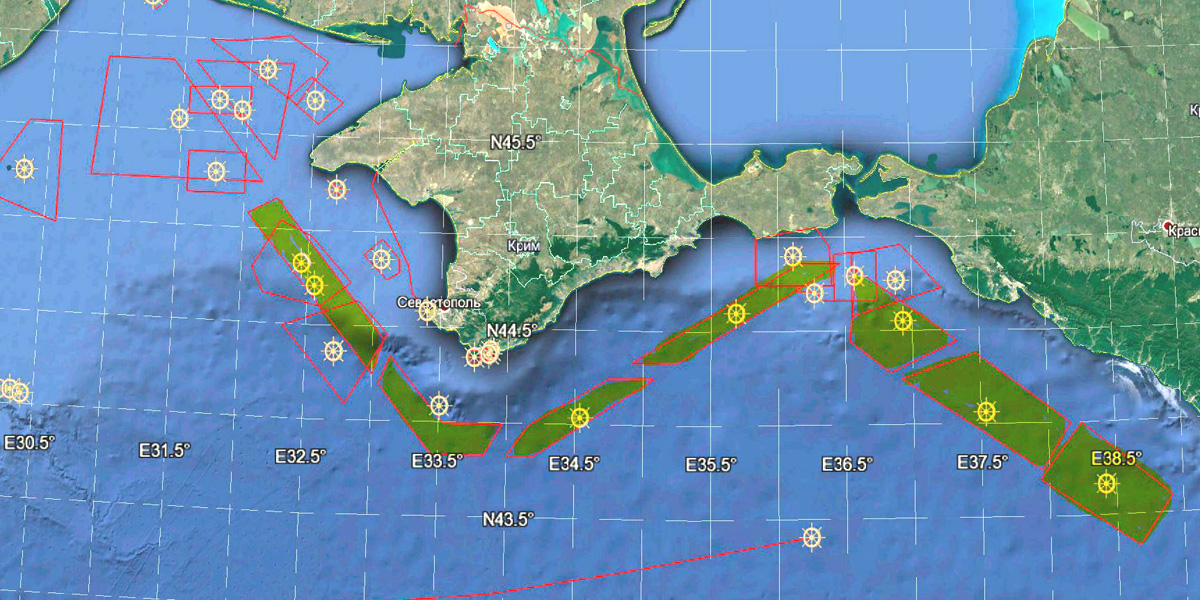

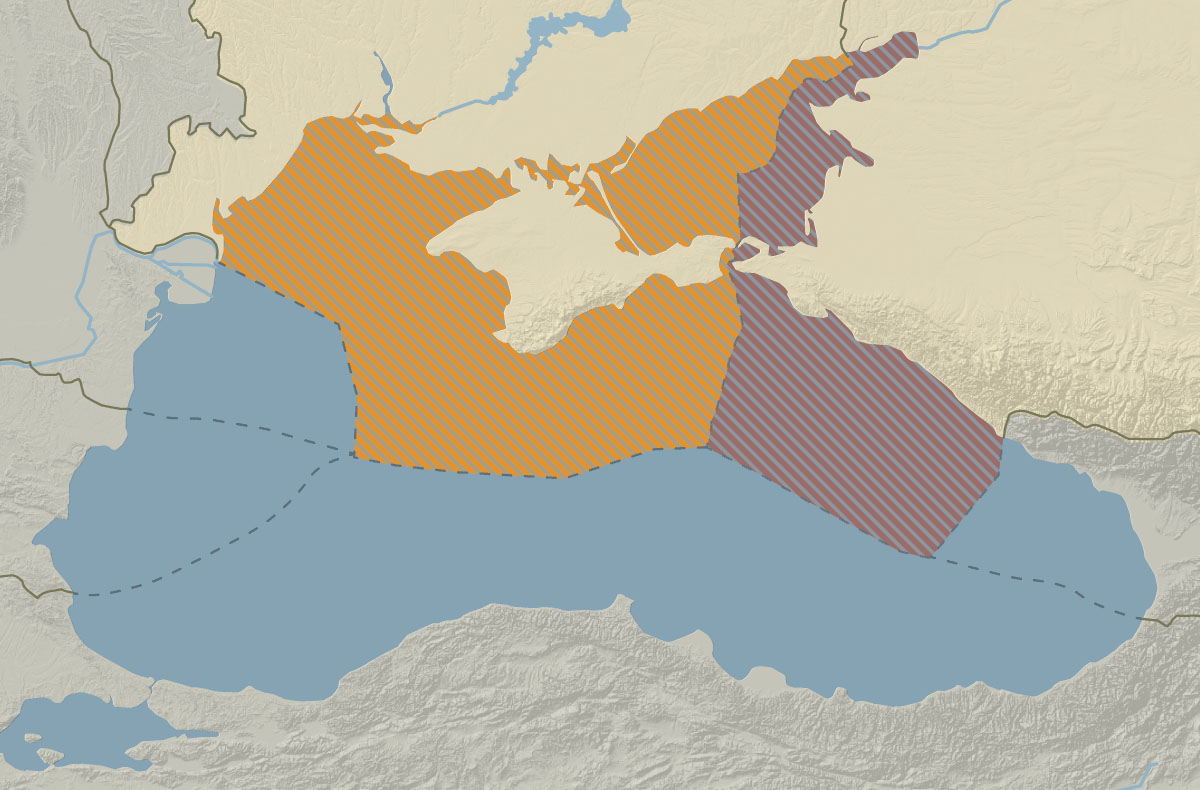

The command of the Ukrainian Navy requested a Coastal Warning as early as 4 April 2021, and Ukrderzhhydrografiya (the national official coordinator) issued Coastal Warnings Nos. 245, 246, and 247 and distributed them via NAVTEX back on 5 June 2021. These areas are marked on the map in grey with the yellow text (See Figure 5).

The coordinator of NAVAREA-ІІІ (the government of Spain represented by Instituto Hidrográfico de la Marina, Cádiz city) did not publish these Ukrainian warnings on its website for 20 days (from 5 June to 24 June 2021). However, during this period, the Spanish coordinator did publish warnings from the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation about the closure of 8 areas of the Black Sea, which were issued on 12, 13, and 14 June 2021 (marked with red lines in Figure 5).

The problem was solved only after the intervention of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine and the Embassy of Ukraine in Spain.

There is information that the Russian Federation is currently trying to resolve with the NAVAREA III coordinator the issue of the de facto recognition of the occupation of Crimea. The current distribution of areas of responsibility among the countries (NAVAREA stations) in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov is shown in Figure 6.

in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov

However, the Russian Federation sees the distribution of areas of responsibility among the countries differently. Russia’s proposals received by the coordinator of NAVAREA-III are shown in Figure 7.

In response to a request from DW, the Hydrographic Bureau of the Spanish Navy said that the publication of the Russian warning was based solely on shipping safety considerations. "Messages transmitted by different countries are guided by these considerations and do not take into account different kinds of regional conflicts between countries," said the NAVTEX Regional Coordination Office in Cadiz.

It is unclear why only one of Russia's three messages was published and what it means for the future in terms of the responsibility of the stations in Berdiansk and Odesa. It is also unclear how to avoid dangerous situations in the future if Ukrainian and Russian stations send different signals at the same time.

For details, see How Russia legalizes annexation in the Black Sea – https://www.dw.com/uk/yak-rosiia-lehalizuie-aneksiiu-u-chornomu-mori/a-57316338 )

3.3. Another Manifestation of Russia's Hybrid War in the Black Sea:

GPS Spoofing Before Sea Breeze-2021

On 18-19 June 2021, HNLMS Evertsen and HMS Defender went from Odesa to Sevastopol and were already going back. The American missile destroyer USS Laboon (DDG58) passed through the Kerch Strait under the bridge on the same night. This is what is called GPS spoofing.

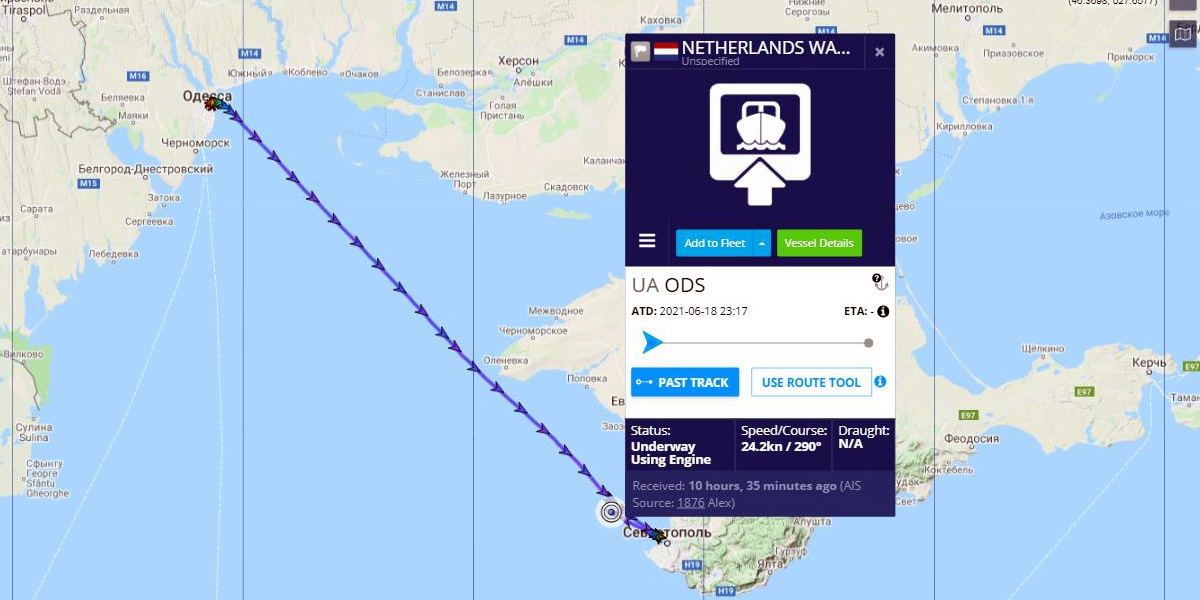

In Figure 8 below, one can see the track of the missile frigate of the Royal Netherlands Navy HNLMS Evertsen (F 805). According to the track from marinetraffic.com, the frigate left Odesa on 18 June 2021 at 23:17 (Kyiv time), reached Sevastopol, and went back to Odesa.

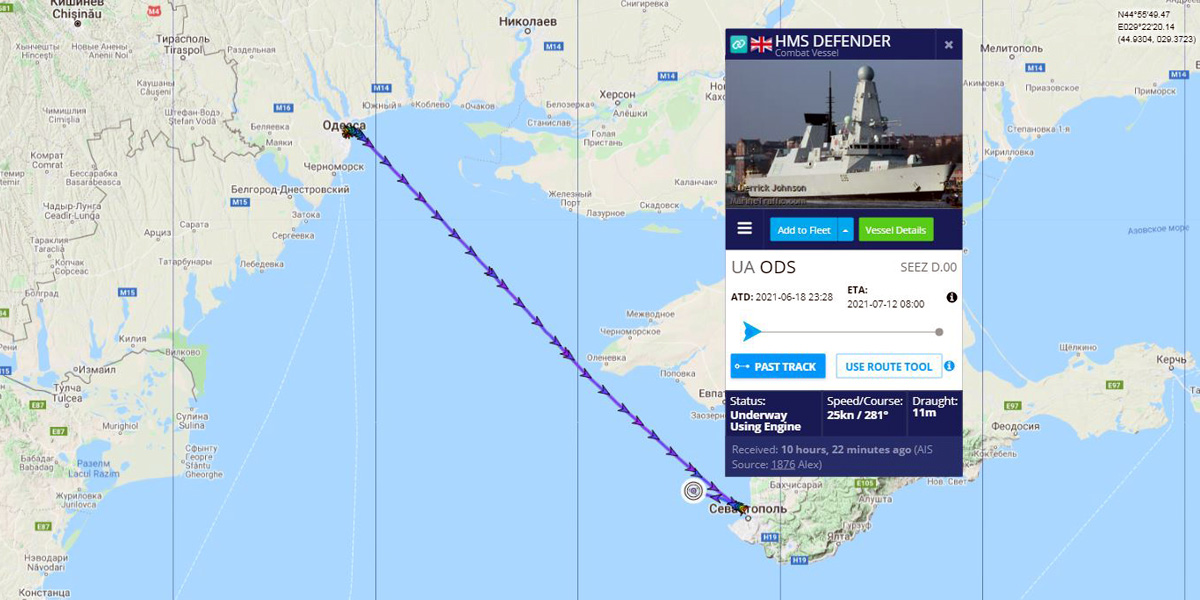

Figure 9 shows the track of the missile destroyer of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy HMS Defender (D 36). According to the track, she also left Odesa on 18 June 2021 at 23:28, together with the frigate Evertsen (F 805), and also reached Sevastopol.

However, for some reason, the hackers who created this virtual voyage have failed to display both ships near Sevastopol at the same time :)

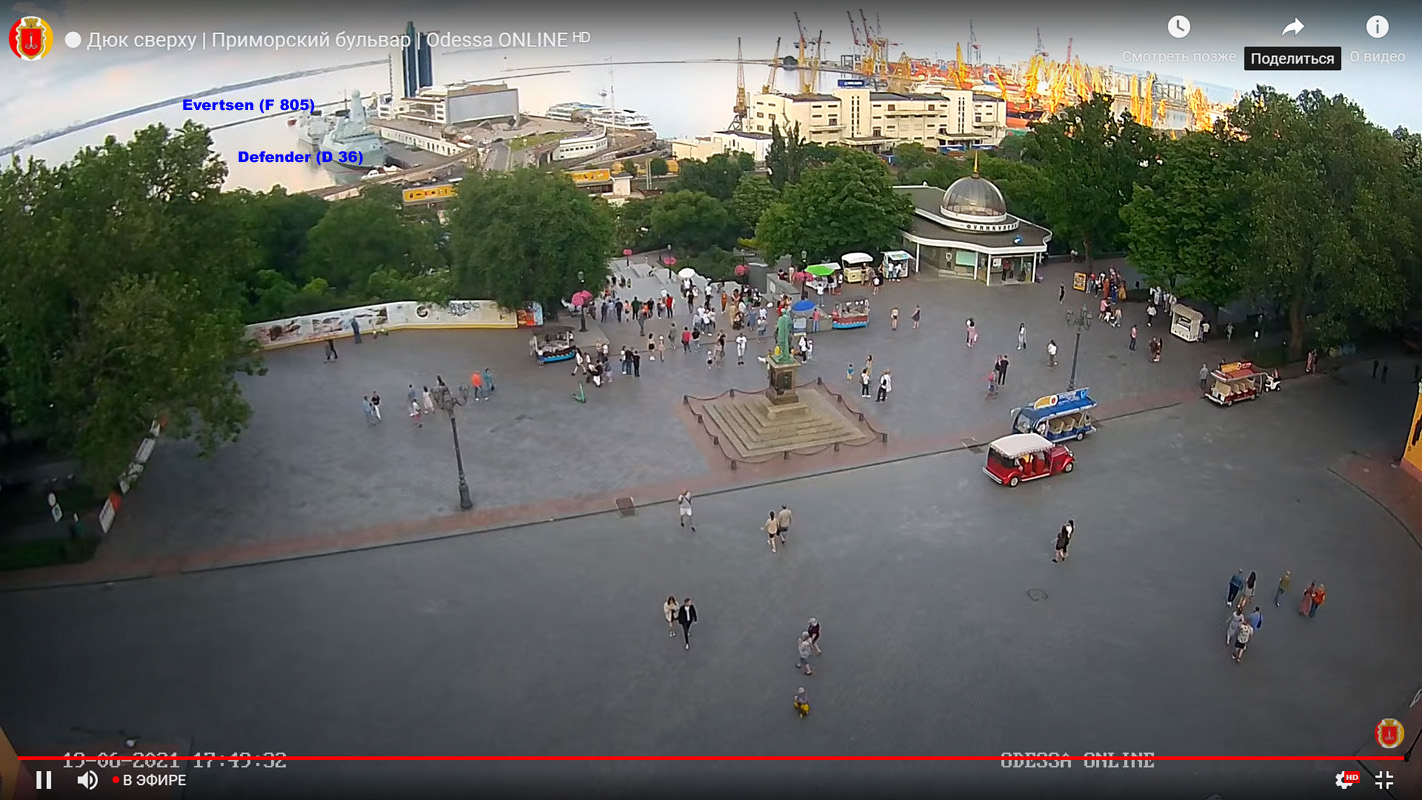

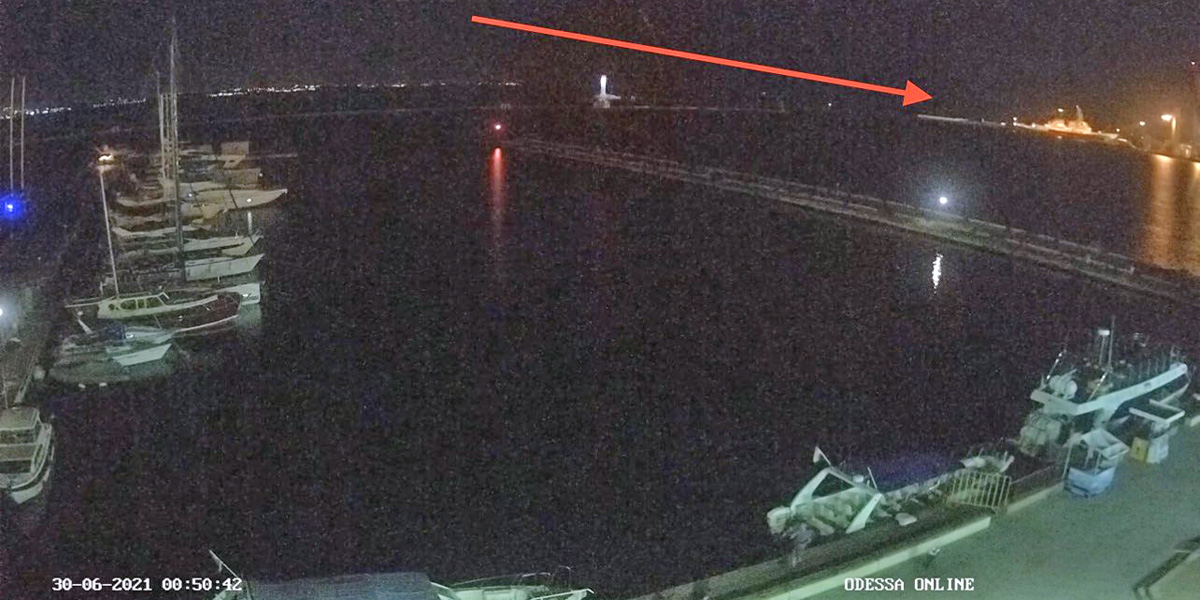

Figure 10 below (the photo has been taken from an online webcam) proves that, in fact, at that time, both ships were staying in the port of Odesa.

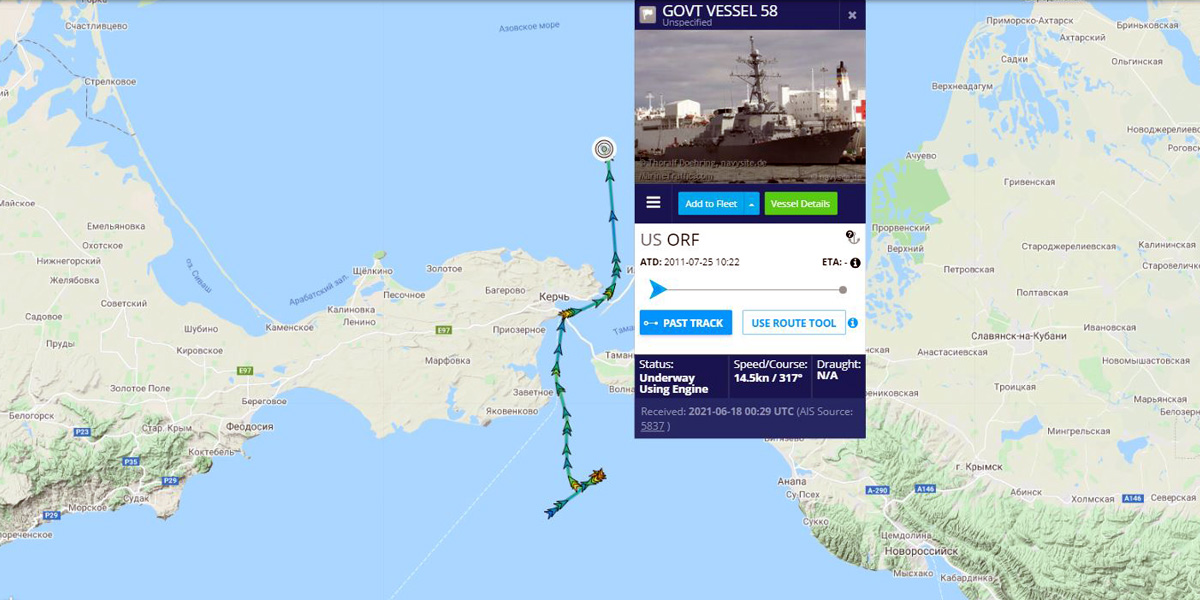

It came as no surprise that, as a result of using the same computer technique, the American missile destroyer USS Laboon (DDG 58) could be seen pass through the Kerch Strait under the bridge to the Sea of Azov on the night of 18 June to 19 June 2021 (See Figure 11 below).

This technique (which is well known to experts) is called GPS spoofing, that is, artificially created signals falsifying the real position of a ship.

Since 2017, our colleagues and we have been recording such activities in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. When looking at the map with dynamic marks, one can see the ship going by land near Rostov. For example, in June 2017, about twenty ships in the Black Sea complained about GPS anomalies, which showed that ships were not moving where they actually were.

GPS anomalies were recorded on the Black Sea coast of Russia around Putin's palace in Sochi. There were incidents involving Russian GPS spoofing during a NATO exercise in Norway, which led to a collision of ships. Besides, spoofing from Syria by the Russian military affected the airport in Tel Aviv.

Note that two days before – on 16 June 2021 – one of the Russian media outlets reported about the "intentions" of the ship of the U.S. Sixth Fleet to pass under the Kerch Bridge.

The last example of GPS spoofing was recorded on the night of 29 June to 30 June 2021. According to the false AIS signal, the USS Ross (DDG-71) missile destroyer of the U.S. Sixth Fleet, together with the Ukrainian Navy missile boat Pryluky (U153), passed near Sevastopol (See Figure 13).

One can already guess that at that same time, the USS Ross (DDG-71) was actually in the port of Odesa. See the photo from the webcam below (Figure 14).

3.4. A Non-Virtual Incident Involving

the Missile Destroyer of the Royal Navy HMS Defender (D 36)

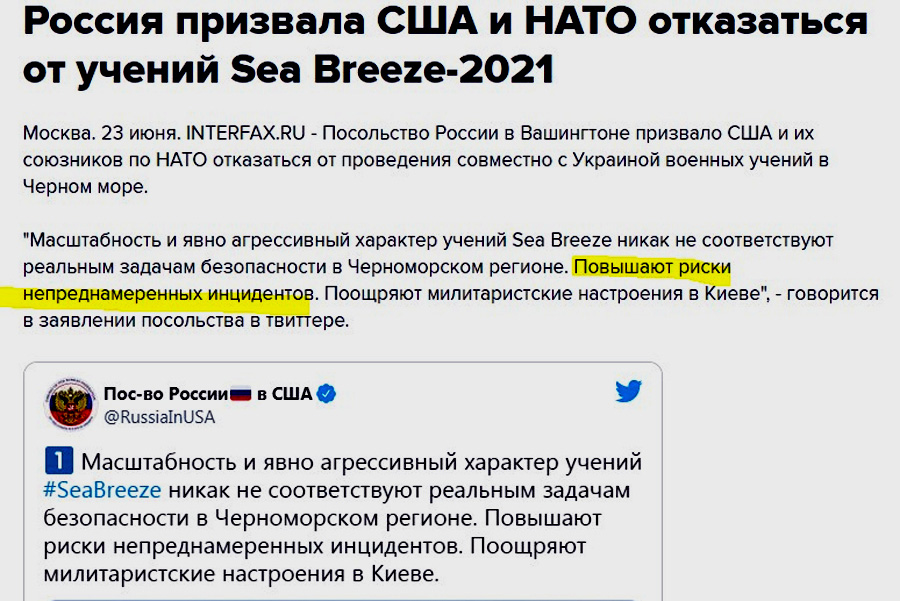

Let's start with the fact that Russia had officially warned that during the Sea Breeze-2021 exercises, there would be "unintentional" incidents. On 22 June 2021, the Embassy of the Russian Federation in the United States of America was first to publish this warning in its Twitter account.

The following morning, on 23 June 2021, this topic was picked up by none other than the leading news agency of the Russian Federation.

Of course, the incidents were not long in coming.

On the same day – on 23 June 2021 – Russian ships tried to interfere with the innocent passage of the missile destroyer of the Royal Navy HMS Defender (D 36) through the standard international route from Odesa to the Georgian port of Batumi. This corridor provides a "shortcut" across part of the 12-mile zone off the coast of the occupied Crimean Peninsula near Sevastopol (See Figure 17 below).

This international route has not changed since Soviet times, and it is marked on all nautical charts. And it really, as experts say, goes 3 miles deep into the 12-mile zone (territorial sea or territorial waters) of Ukraine near Crimea.

During this passage, the Pavel Derzhavin patrol corvette (hull number 363) of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet warned the Defender to change the course for her own safety. In turn, the British destroyer replied that she had received the message and was on her way to her destination.

Despite warnings of possible use of weapons and gunshots heard at a distance in the neighbouring Black Sea area, where Russia was conducting its exercises, as well as despite numerous (up to 20) flights, the British destroyer HMS Defender (D 36) did not change the course.

In the end, it turned out that the actions of the HMS Defender (D 36) could be interpreted as a Freedom of Navigation Operation (FONOP) – i.e. responding to operational challenges against excessive maritime claims, which demonstrate the resistance of leading states to excessive maritime claims.

3.5. Another Non-Virtual Incident – With the Missile Frigate

of the Royal Netherlands Navy HNLMS Evertsen (F 805)

On the following day – 24 June 2021 – during the presence in the Black Sea of the missile frigate of the Royal Navy of the Netherlands HNLMS Evertsen (F 805), Russian aircraft created a dangerous situation near this ship.

"Armed Russian aircraft provoked a dangerous situation in the Black Sea near the HNLMS Evertsen last Thursday. The plane repeatedly flew at dangerously low altitudes above and near the ship and performed simulation attacks. During these persecutions, the HNLMS Evertsen was in international waters," the Dutch Defence Ministry said in a statement issued on 29 June 2021.

Dutch Defence Minister Ank Beyleveld-Schouten called Russia's actions "irresponsible."

"Evertsen has every right to sail there. There is no excuse for such aggressive actions, which unnecessarily increase the likelihood of accidents," she said, adding that the authorities would discuss the issue with Russia at the diplomatic level.

3.6. A New Russian Technique for Hybrid Warfare:

The "Protective Barrier of Fake Exercises" Around the Occupied Crimean Peninsula

In September 2020, for the first time, Russia blocked almost the entire maritime perimeter of the occupied Crimean Peninsula outside the 12-mile zone under the pretext of exercises.

For example, see the map of closed Black Sea areas as of 21 September 2020, which are marked in green (Figure 18).

The closure of the perimeter of the Crimean Peninsula by the Russian Federation lasted continuously for almost 3 months, from 17 September to 9 December 2020.

This technique was used again from 15 January 2021 to 8 February 2021 and later from 22 February 2021 to 12 March 2021. Such closures usually coincided with the presence in the Black Sea of ships from non-Black Sea NATO countries – namely reconnaissance ships, modern missile destroyers, and cruisers.

Russia has been closing off large areas of the Black Sea for a long time. However, each time it moves further and further, both in terms of the size of the closed areas and the duration of the closure. That is, the RF is testing the limits of response to its further steps.

Against this background, the situation with the closure of large areas of the Black Sea in April 2021 for the period from 24 April 2021 (later retrospectively changed to 16 April 2021) to 31 October 2021, i.e. for more than 6 months, is not surprising. This is just the next step in terms of the duration of closures.

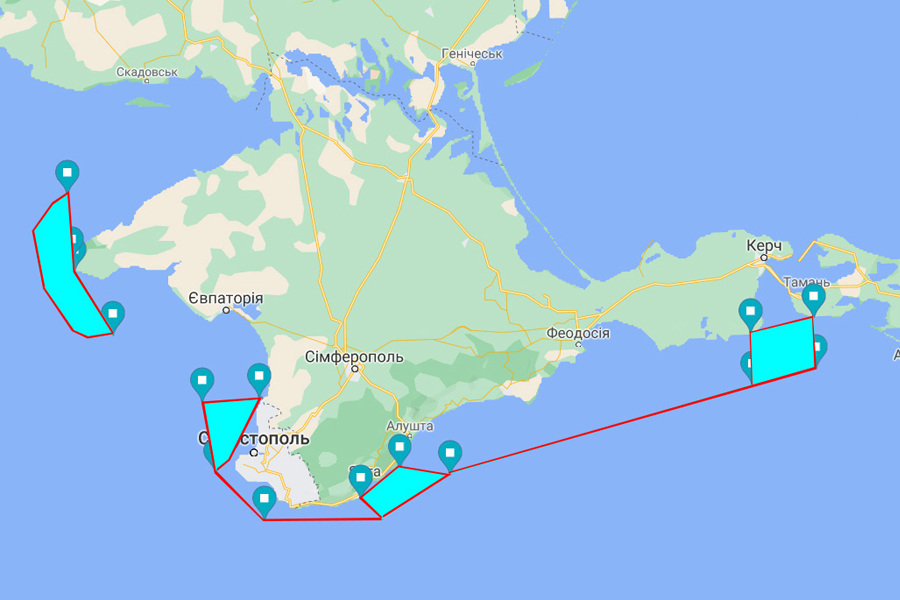

The map of the closures initially looked as shown in Figure 19. These were the closed areas of the Black Sea according to Coastal Warning NOVOROSSIYSK 152/21 of 7 April 2021. It was published in issue No. 17/21 of the weekly bulletin of the Department of Navigation and Oceanography of the Russian Ministry of Defence.

The main peculiarity of this action is that, for the first time, the approaches to the Kerch Strait were blocked − so far only for military and other state vessels. Previously, there had always been a free corridor between closed areas.

A few days later, the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation cancelled Coastal Warning No. 152/21 (Point B of which contained the coordinates of the area blocking the approaches to the Kerch Strait) and replaced it with a new Coastal Warning No. 169/21. In it, the coordinates of the closed area near the Kerch Strait remained the same as before. However, the configuration of closed areas near Sevastopol changed: the RF remembered that it was undesirable to block traditional international sea routes passing near Sevastopol. The map of closures then looked as shown in Figure 20.

In addition, while in Coastal Warning No. 152/21, the start date of the closure was 24 April 2021, in the new Coastal Warning No. 169/21, it was 16 April 2021 (changed retrospectively). The end date didn’t change: 31 October 2021.

Thus, Russia is wreaking havoc on the international system, which is designed to ensure the safety of navigation, and is gradually asserting its intentions to turn the Black Sea into a Russian lake.

3.7. The Detention of Ukrainian Fishermen From Ochakiv in the Black Sea

Between Crimea and Odesa by the Russian Coast Guard on 20 April 2021

On 20 April 2021, 40 miles northwest of Cape Tarkhankut (or 50 miles from Odesa), the FSB Coast Guard detained the Ukrainian fishing boat YaOD-2483 from Ochakiv.

The Russian message read: "Citizens were catching turbot in the economic zone (!!) of the Russian Federation. On 21 April, the court found the captain of the detained vessel guilty. The fine of 257 thousand roubles was imposed on the perpetrator. In addition, nets were confiscated from the poachers."

The boat was brought to the Chornomorske urban-type settlement in occupied Crimea. After the fine was imposed, the fishermen were released.

3.8. Claims of the Russian Federation on the Part of the Maritime Exclusive Economic Zone

of Ukraine Adjacent to the Occupied Crimean Peninsula

Note that the case of the detention of fishermen mentioned above is not unique. What is unique is that Russia is increasingly publicly calling the Black Sea area where the fishermen were detained "Russia's maritime exclusive economic zone."

However, it's not just about fishermen – such "arguments" are the basis for blocking Black Sea areas under the pretext of military exercises, attempts to prevent the free passage of ships and vessels near the occupied Crimean Peninsula, and gas production on Ukrainian offshore platforms on the Black Sea shelf seized in the spring of 2014.

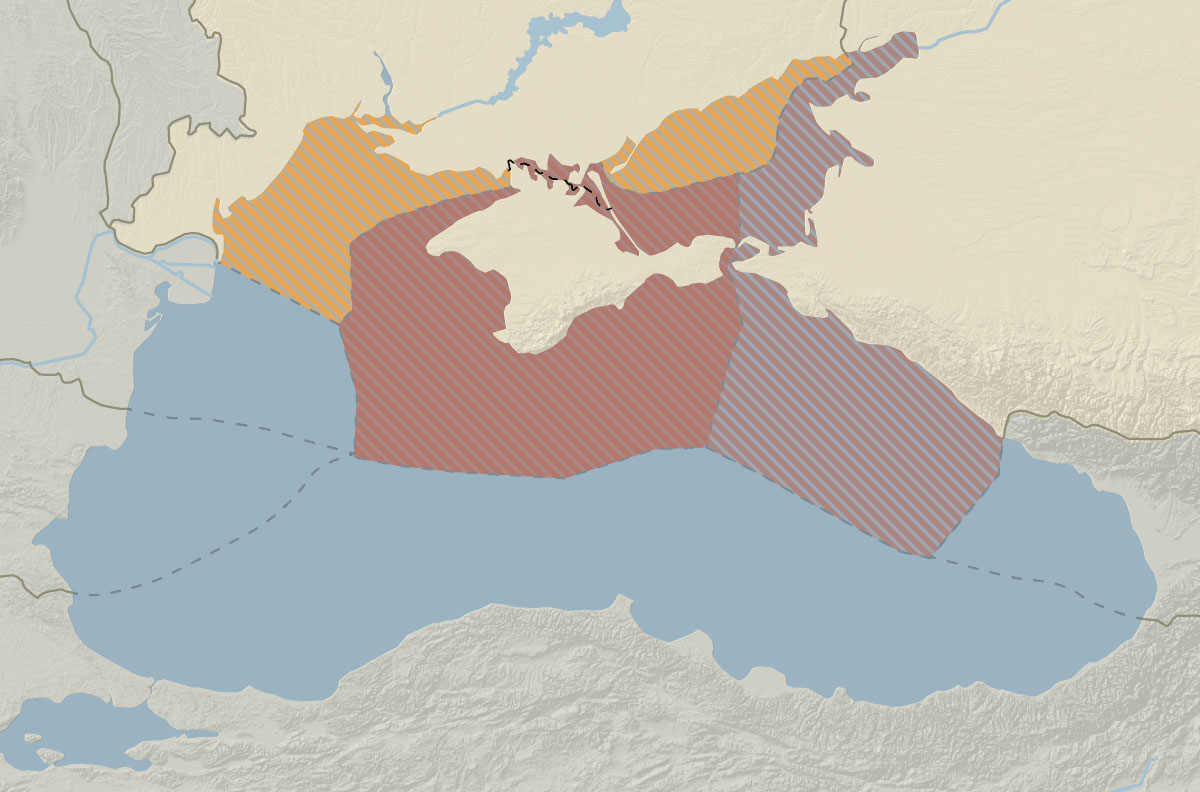

The map of maritime exclusive economic zones in the Black Sea is shown in Figure 22.

Russia’s claims to maritime exclusive economic zone, which have been increasingly asserted by its actions since the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula, are shown in Figure 23.

Moreover, Russia takes advantage of the fact that for 30 years after the collapse of the USSR, it has been blocking and delaying negotiations on the establishment of land and sea borders with Ukraine. Ukraine has established the borders of the maritime exclusive economic zone with Romania and Turkey, but not with the Russian Federation.

4. The Forecast About the Developments in the Black Sea

and the Sea of Azov

Russia's claims to the Ukrainian territorial sea and the maritime exclusive economic zone may be and will be more extravagant.

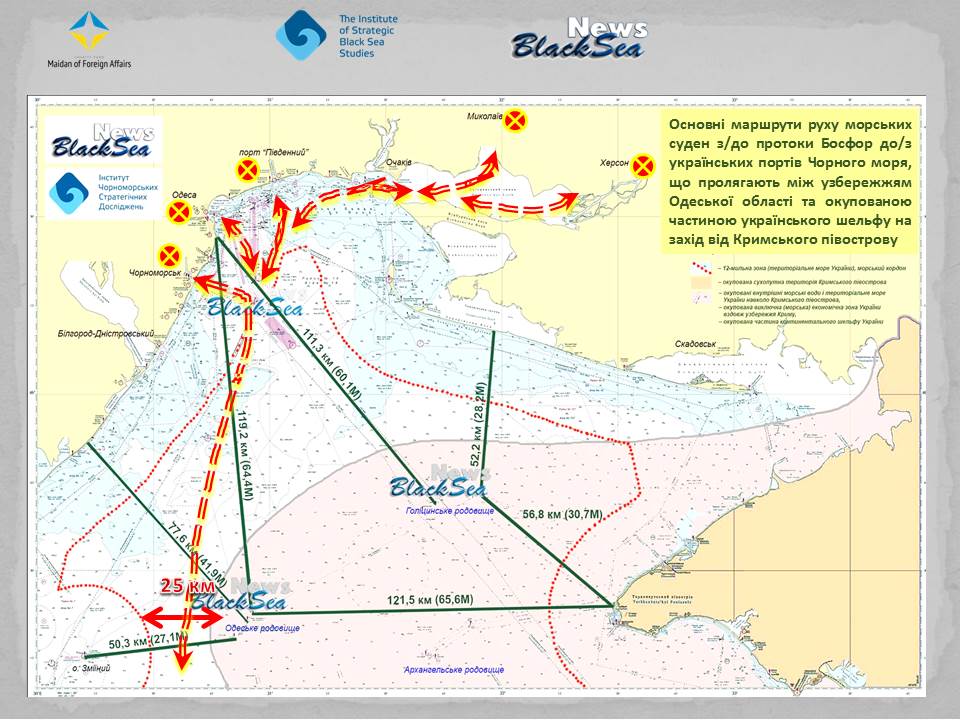

Exports from Ukrainian ports on the Sea of Azov account for only 5-7% of Ukraine's maritime exports. The remaining 95% of exports go through the ports of the Odesa region, Mykolaiv, and Kherson. The main export-import routes of Ukraine are in the Black Sea and lead to/from the Bosphorus.

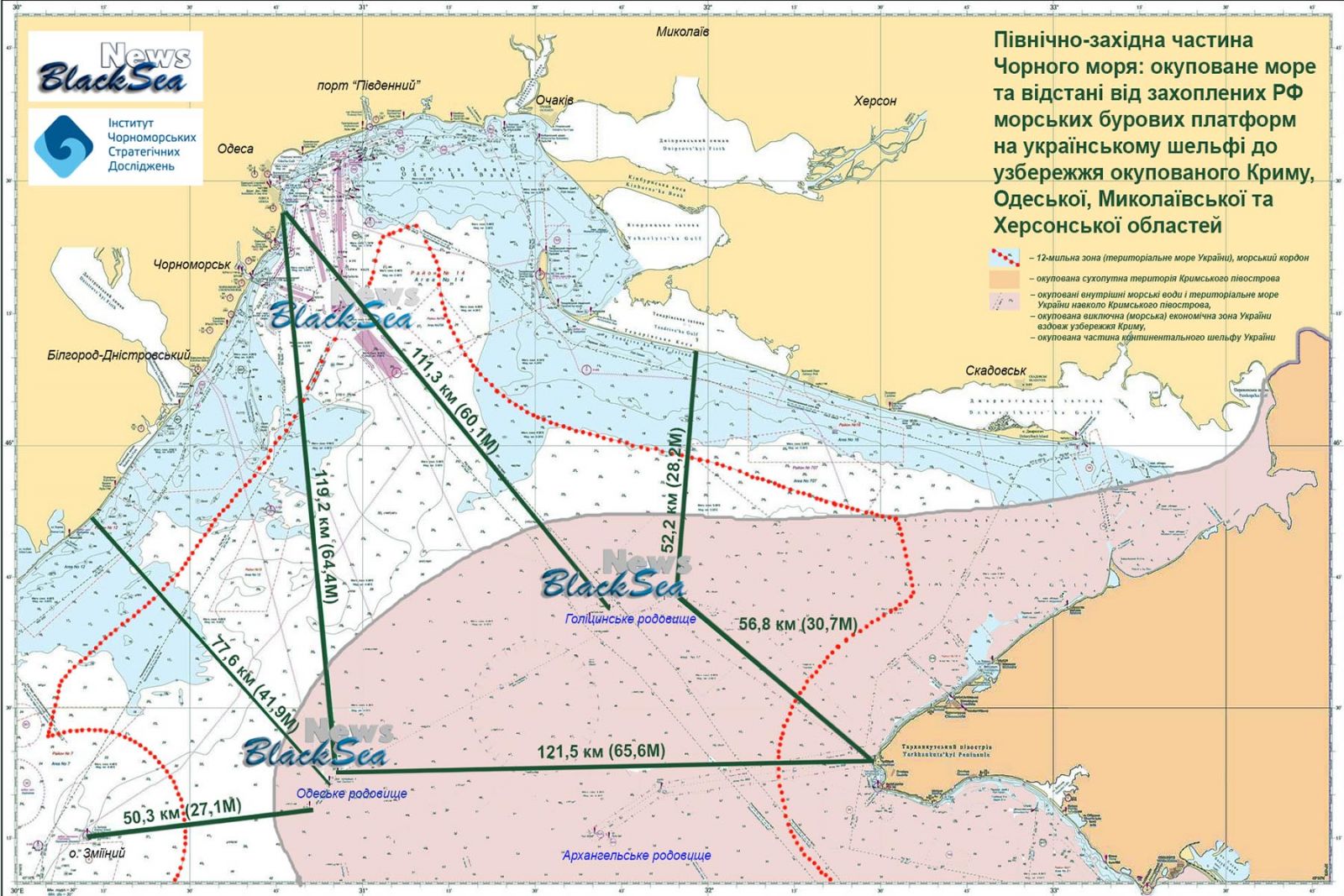

In the Black Sea – near the recommended sea routes from Odesa to the Bosphorus and from Odesa to Batumi and Turkish Black Sea ports – the Ukrainian offshore oil platforms are situated, which were captured by Russia during the occupation of Crimea (See Figures 24, 25).

A situation seems very likely, in which Russian warships will start checking commercial vessels going from Ukrainian ports to the Bosphorus past the seized Ukrainian offshore gas and oil platforms (which Russia has long considered "theirs"), using the "Azov technique," that is, under the pretext of the possible presence of saboteurs and explosives onboard the vessels.

In other words, in the near future, Russia will be increasingly trying to secure the de facto occupation of the Ukrainian Black Sea shelf almost to the coast of the Odesa region.

5. What Else Ukraine Together With NATO

and EU Countries Should Do to Prevent a Threat From the Sea

5.1. The Policy of Maritime and Naval Non-Recognition

of the Illegal Attempt to Annex the Crimean Peninsula and the Creeping Occupation

of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov

The authors suggest establishing international rules in the maritime and naval spheres, including navigation and cartography, which develop and specify the UNGA Resolution of 27 March 2014 calling for non-recognition of Russia's attempts to illegally alter the status of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol and for refraining from any actions, inaction, or steps that might be interpreted as recognising such altered status.

This includes, for example, a ban on the publication, distribution, and display in any form of geographical maps and nautical charts, which would indicate the "belonging" of the Crimean Peninsula to the Russian Federation and, accordingly, the "belonging" of parts of Ukrainian maritime exclusive economic zone in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov to the RF.

In addition, this may include refusing to service warships and support vessels of the Russian Navy in NATO and EU ports and so on.

5.2. Applying the Updated "Crimean-Azov Package of Sanctions"

To impose international sectoral sanctions on the entire Russia's shipbuilding industry for collaboration on the construction of military equipment at seized Ukrainian plants in occupied Crimea, as well as for the organization of and participation in the maintenance of ships and missile systems of the Black Sea Fleet at seized Ukrainian plants in Crimea.

Reference. Almost 150 defence and other plants of the Russian Federation – from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok (mostly shipbuilding and instrument-making enterprises) – have "surfaced" as participants in these activities. The vast majority of these companies are not under sanctions.

To impose international sanctions against those Russian shipowners, insurers, and classification societies that were engaged in the operations of seagoing vessels visiting the seaports of the Crimean Peninsula in violation of sanctions.

To impose international sanctions on Russian ports on the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, namely Port Kavkaz, Rostov-on-Don, Temryuk, Azov, and Novorossiysk, for regular shipping from these ports to the occupied Crimean Peninsula.

This sanctions package may include the following:

1) The prohibition of providing any services for merchant ships departing from the aforementioned ports for the ports of Ukraine, the EU, the U.S.A., the Commonwealth of Nations, and other countries (except for emergencies and disasters).

2) The prohibition of organising voyages to these ports from the ports of Ukraine, the EU, the U.S.A., the Commonwealth of Nations, and other countries.

3) The prohibition of shipping sea cargoes that have been transhipped or are planned for transshipment at the Port Kavkaz roadstead to/from the ports of Ukraine, the EU, the U.S.A., the Commonwealth of Nations, and other countries.

5.3. A Set of Actions to Deter Russian Aggression in the Black Sea

To support Ukraine through the UN in forcibly establishing a maritime border with Russia in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov, and the Kerch Strait and the delimitation of maritime areas with Russia on the basis of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

To create in the future an A2/AD (anti-access and area denial) area in the area between the Deveselu military base, Romania, and the Odesa naval base, Ukraine, so that it protects the sea and air space in the area of the Black Sea coast of Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Romania and guarantees the security of the only route for commercial shipping to Black Sea ports of Ukraine, not controlled by Russia.

To carry out continuous (365 days a year) naval and air patrols of the main route of merchant ships in the Black Sea from the Bosphorus in the general direction of Odesa, including the Black Sea area from the Dnieper-Bug estuary (Ochakiv) to the Danube Delta (Vilkovo) and the area of gas and gas condensate fields seized by Russia in Ukraine’s EEZ in 2014.

For this purpose, to further increase the number of NATO Navy ships on duty in the Black Sea.

To establish in the Black Sea a joint naval format of NATO, including its Black Sea member states and partner countries (Ukraine and Georgia), for regular patrols in the Black Sea to ensure freedom of navigation.

To initiate an international investigation into GPS spoofing in the Black Sea area by Russia.

To support Ukraine in monitoring violations of freedom of navigation by the RF in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov and initiating relevant decisions on them in international organizations (the IMO, the ICAO, the FAO, the International Telecommunication Union, the Council of Europe, the EU), courts (the ITLOS, the ECHR), and arbitration tribunals. In particular, this may apply to the restriction of shipping, fishing, mass abuses of sea areas closures under the pretext of military exercises, using the international system of maritime navigation warnings about the dangers NAVTEX, and so on.

To initiate an international investigation into the use of Crimea as a naval base for Russian aggression in Syria, Libya, etc.

In developing the proposals, in addition to the works by the authors, the contributions from the experts of the Maritime Expert Platform have been used. роботи експертів Морської експертної платформи.

* * *

This publication has been produced with the support of the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Its contents do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of EED. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this publication lies entirely with the authors.

This publication has been produced with the support of the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Its contents do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of EED. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this publication lies entirely with the authors.

More on the topic

- 26.01.2022 The 2021-January 2022 presence of non-Black Sea NATO states’ warships in the Black Sea

- 14.12.2021 The Presence of NATO Non-Black Sea States’ Warships in the Black Sea in November-December 2021

- 21.08.2021 The Militarization of Crimea as a Pan-European Threat and NATO Response. Third Edition

- 17.07.2021 The Presence of NATO Non-Black Sea States’ Warships in the Black Sea in 2013-2021 / The Database

- 04.03.2015 Standing NATO Maritime Group 2 Begins Operations in the Black Sea / Photo