The Militarization of Crimea as a Pan-European Threat and NATO Response. Third Edition

Andrii KLYMENKO

Tetyana GUCHAKOVA

the Monitoring Group of the Black Sea Institute of Strategic Studies and BlackSeaNews

© A. Klymenko, T. Guchakova. The Militarization of Crimea as a Pan-European Threat and NATO Response. Third edition. Based on the data gathered by the joint Monitoring Group of the Black Sea Institute of Strategic Studies and the BlackSeaNews online publication, www.blackseanews.net. With contributions by O. Korbut. Kyiv. 2021. Translated from Ukrainian by Hanna Klymenko.

This online book is a revised and updated edition based on the two separate books published in 2019: The Militarization of Crimea as a Pan-European Threat and The Black Sea Threat and NATO Response.

The situation on the temporarily occupied territory of Crimea has been monitored, and this edition of the book has been prepared with the support of the European Programme of the International Renaissance Foundation. The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.

Contents

The Reality of the Militarization of Crimea

The Chronicle of the Occupation of Crimea and the Beginning of its Militarization

The Build-Up of Coastal and Naval Missile Capabilities in Occupied Crimea

The Crimean Military-Industrial and Service Base of the Occupying Force Grouping

Occupied Crimea and the Change of the Region's Military Balance

The Restoration of the Crimean Nuclear Infrastructure

The Size and Composition of the Force Grouping in Crimea

NATO's Black Sea Dilemma

Occupied Crimea in the Syrian War

The Black Sea History of NATO's Naval Forces

NATO's Naval Presence in the Black Sea in 2014-2021

Current Naval Trends and Forecasts

The Reality of the Militarization of Crimea

Since the first days of the occupation of Crimea, the authors of this report, who happened to be not just witnesses to that special operation by the Russian Federation (RF) but also the resistance participants, have had no doubt that the only goal of Putin's brazen venture was to build up the peninsula as a military base, which in turn, was intended to radically change the geopolitical and military-strategic balance in Europe and the Mediterranean.

However, in the first year of the occupation – roughly until mid-2015 – Russia tried to "sell" to the shocked world and its own population a shiny array of ideas as to the non-military, but rather, tourist, investment, and technological development of its new booty. According to those ideas, Crimea was to become the new Russian showcase that would surpass even Olympic Sochi. Unfortunately, many people not only in Russia but around the world believed that.

In truth, though, since the very beginning of the occupation of Crimea, Russia has been consistently implementing its only target programme – that of the peninsula's military build-up. A telling marker was that the "Ministry of Crimean Affairs" created two weeks after the illegal annexation, on 31 March 2014, was dissolved as early as 15 July 2015.

On 28 July 2016, the status of occupied Crimea and Sevastopol within Russia was lowered – Putin's decree eliminated the Crimean Federal District, which was created immediately after the annexation, on 21 March 2014.

The so-called "constituent entities of the Russian Federation" – the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol – were included in the Southern Federal District with the administrative centre in Rostov-on-Don. That act established a uniform system for the political and administrative governance and the military command because since the beginning of the occupation, all Russian military units in Crimea had been part of the Southern Military District with the headquarters in Rostov-on-Don.

The militarization of Crimea became not only the main content of Russia's Crimean policy but also the main driver of the occupied peninsula's economy. As a result, over the years of the occupation, it was the military development of that territory that has become the most striking "success story" of the Russian Federation in Crimea:

- building up the largest in Europe Russian joint (multi-service) force in Crimea at a rapid pace is underway;

- since the first days of the occupation, Crimea has been receiving only the newest and cutting-edge military equipment as a matter of priority;

- all Soviet-time military infrastructure and facilities in Crimea, such as numerous military airfields, missile launching sites, air defence facilities, radar systems, and nuclear weapons storage facilities, are currently being restored;

- a new fortified area in the north of Crimea has been created and is being developed;

- the construction of new and reconstruction of old military compounds for the deployment of new military units, as well as the construction of housing and related infrastructure for the military is underway;

- the number of members of armed forces and special services personnel is growing;

- to fulfil military orders, the operations of the military-industrial enterprises specializing in military instrument-making, shipbuilding, and ship repair have been resumed as a matter of priority. These enterprises have been included in the structures of Russian state-owned concerns.

All other areas of life in Crimea – economy, social services, human rights, information space, and national politics – now serve the ideology of a lodgement area.

The Chronicle of the Occupation of Crimea

and the Beginning of its Militarization

The military development of Crimea began in the first days of the occupation. The special operation of the Russian Federation to seize Crimea started three days before the end of the Winter Olympics in Sochi that lasted from 7 to 23 February 2014.

On 20 February 2014, a column of armoured vehicles left the base of the 810th Marine Brigade of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Kozacha Bay of Sevastopol, heading out of the city. The official explanation was that the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea put its regiments on a heightened alert in view of the difficult political situation in Ukraine, meaning that the marines would enhance the security of the Black Sea Fleet units throughout the peninsula – in addition to Sevastopol, the Fleet had a maritime aviation airfield in the village of Hvardiiske near Simferopol and a base in Feodosiia.

On 20-23 February 2014, the Separate Special Forces Brigade of the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (GRU) was sent from Tolyatti, Russia, to Crimea to "protect a strategic object."

On 23 February 2014, Sevastopol de facto got under Russian control – the city rally elected a "people's mayor" and created the "detachments of self-defence." The "self-defence" was aided by Russian soldiers wearing uniforms without insignia, who were nicknamed "little green men."

On 23 February 2014, the Winter Olympics in Sochi ended and Russian Black Sea Fleet ships that ensured the safety of the Games headed straight from the sea to Novorossiysk.

On 24 February 2014, Russian armoured personnel carriers completely blocked the entrance to Sevastopol. The city became the starting point for the occupation of Crimea because, in accordance with the Ukraine-Russia treaty, it was there that Russia's Black Sea Fleet headquarters, most its ships, and naval infantry were based.

On that very day, in Novorossiysk, the "Olympic" fleet of the Black Sea Fleet took on board special operations units of the Russian Airborne Troops and marines, as well as military equipment for the occupation of Crimea, and set sail for Sevastopol.

Below is the list of vessels stationed in the Sochi-Novorossiysk area of the Black Sea during the Winter Olympics:

- The missile cruiser Moskva – left Sevastopol on 3 February 2014.

- The patrol boat (frigate) Smetlivyy – left Sevastopol on 3 February 2014.

- The anti-submarine corvette Alexandrovets – left Sevastopol on 4 February 2014.

- The anti-submarine corvette Muromets – left Sevastopol on 4 February 2014.

- The ocean minesweeper Kovrovets – left Sevastopol on 4 February 2014.

- The ocean minesweeper Turbinist – left Sevastopol on 4 February 2014.

- The reconnaissance ship Priazovye – left Sevastopol on 4 February 2014.

In addition, the Russian Navy squadron in the Black Sea included large amphibious ships of the Black Sea, Northern, and Baltic fleets that regularly provided for the military contingent of the Russian naval base in Tartus, Syria, and delivered military equipment to the Syrian Assad regime from the Russian Black Sea Fleet naval base in Novorossiysk.

During the special operation to occupy Crimea – from 20 February to 25 March 2014 – there were 9 large amphibious ships in the Black Sea:

- 5 large amphibious ships of the Black Sea Fleet: Saratov (No. 150), Nikolai Filchenkov (No. 152), Novocherkassk (No. 142), Yamal (No. 156), and Azov (No. 151).

- 2 large amphibious ships of the Baltic Fleet of the Russian Federation: Kaliningrad (No. 102) and Minsk (No. 127).

- 2 large amphibious ships of the Northern Fleet of the Russian Federation: Olenegorskiy Gornyak (No. 112) and Georgiy Pobedonosets (No. 016).

Also, at least nine other ships of the Black Sea Fleet that were based at the Novorossiysk naval base and eight ships of the Coast Guard of the Border Service of the FSB were present in the Black Sea at that time.

On 25 February 2014, after the Olympics, the squadron of the Russian Black Sea Fleet returned to already seized Sevastopol, delivering several thousand paratroopers and weapons from Novorossiysk.

The main logistical role in the occupation and further militarization of the Crimean Peninsula belonged to the large amphibious ships of Russia's Black Sea and other fleets and the Kerch Strait ferry crossing.

The seriousness of the situation could be evidenced by the fact that in those days, in Sevastopol, the Black Sea Fleet compiled the lists of the servicemen family members for the event of an evacuation, while marine units were put on heightened alert.

On 25 February 2014, a Special Forces unit of the GRU of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia arrived from Ulyanovsk in Crimea.

On 27 February 2014, the reconnaissance and sabotage group of the special operations unit of the Russian Airborne Troops, which arrived from Sevastopol in uniforms without insignia, seized the Verkhovna Rada and the Council of Ministers of Crimea in Simferopol.

On 28 February 2014, the exit from Balaklava Bay (Sevastopol), where Ukraine's Coast Guard ships were stationed, was blocked by Russia's Black Sea Fleet missile boat Ivanovets (No. 954), while the base of the Ukrainian maritime border security forces in Balaklava was surrounded by special forces of the Russian Federation.

On that same day, a column of armoured vehicles, including Tigrs and other equipment previously not in service of the Russian military units in Crimea, headed from Sevastopol and the Hvardiiske Black Sea Fleet airfield near Simferopol towards the Crimean capital, while the special forces of the Russian Federation seized Simferopol airport and Belbek airport in Sevastopol.

The mobile coastal anti-ship missile systems Bastion and Bal, the operational-tactical missile systems Iskander, the anti-aircraft systems S-400 and Pantsir, and guided-missile carrier aircraft arrived in Crimea in the first weeks of the occupation.

On 1 March 2014, the Russian President asked the Federation Council to authorize the use of Russian troops in Ukraine "until the socio-political situation stabilizes" with the request granted. On the same day, two large amphibious ships of the Baltic Fleet of the Russian Federation, Kaliningrad (No. 102) and Minsk (No. 127), with paratroopers and equipment from Novorossiysk entered Sevastopol.

Also, on 1 March 2014, both Feodosiia Gulf and Port were blocked by a missile hovercraft of the Black Sea Fleet (there are two such ships in Russia's Black Sea Fleet, Bora and Samum).

On 2 March 2014, two large amphibious ships, Olenegorskiy Gornyak (No. 112) and Georgiy Pobedonosets (No. 016), of the Russian Northern Fleet arrived in Sevastopol, carrying on board paratroopers and equipment from Novorossiysk. On the same day, the marine battalions of the Ukrainian Navy in Feodosiia and Kerch and the garrison of the coastal defence brigade of the Ukrainian Naval Forces in the Perevalne village were blocked. The building of the Representative Office of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the headquarters of the Azov-Black Sea Regional Division and the Simferopol border detachment of the Border Service of Ukraine were seized.

On 3 March 2014, ships and auxiliary vessels of Russia's Black Sea Fleet blocked the exit from Sevastopol Bay to prevent the possible exit of the Ukrainian Navy ships or the entrance of the Ukrainian Navy flagship frigate Hetman Sahaidachnyi (U130).

That day marked the start of Russia's military blockade of all Ukrainian military units in Crimea that lasted until 25 March 2014.

The Commander of the Black Sea Fleet of the RF, Admiral Aleksandr Vitko, declared an ultimatum to the Ukrainian servicemen: if they did not surrender by 5 a.m. on 4 March 2014, Russian troops would begin the attack on all units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine throughout Crimea. The ultimatum to the Ukrainian military units was delivered by Russian servicemen.

On the same day, Russian special forces seized the border crossing point at the Kerch Strait ferry crossing and the Kerch coastguard detachment.

On 5 March 2014, five large amphibious ships of the Russian Navy – the Baltic Fleet amphibious ships Minsk (No. 127) and Kaliningrad (No. 102), the Northern Fleet ships Olenegorskiy Gornyak (No. 112) and Georgiy Pobedonosets (No. 016), and the Black Sea Fleet ship Azov (No. 151) – arrived in Sevastopol with troops and equipment from yet another trip to Novorossiysk. At least 300 people and 20 vehicles were unloaded from each ship. Seven armoured personnel carriers BTR-80 and a number of antitank missile systems Shturm were unloaded from the amphibious ship Azov. In the meantime, on the west coast of the Crimean Peninsula, at the entrance to Lake Donuzlav, where the Ukrainian Navy base was located, the Russian Black Sea Fleet flagship missile cruiser Moskva, the physical field control ship SFP-183, the small-size missile ship (corvette) Shtil, and a Molniya-type missile boat controlled the exit from the lake in the Black Sea.

On 6 March 2014, at the entrance to Lake Donuzlav near Yevpatoriia, where the Ukrainian Navy ships were based, the Russian Black Sea Fleet blew up and sank its own old decommissioned major anti-submarine ship Ochakov and the rescue tug Shakhtar to block the shipping route and prevent the Ukrainian ships from leaving for Odesa.

As of 7 March 2014, Russian troops in Crimea had taken all the administrative buildings, blocked all the access ways to the peninsula, and surrounded all the bases and military units of the Armed Forced of Ukraine. Russian warships had delivered to the peninsula about 10 thousand soldiers and equipment, including mobile anti-ship coastal defence missile systems.

On 14 March 2014, an echelon with 14 anti-aircraft missile systems S-300 PMU travelled via the Kerch Strait ferry crossing by train to the Crimean interior. That is, as early as mid-March 2014, the Russian Federation started to develop the missile capability of occupied Crimea.

The Build-Up of Coastal and Naval Missile Capabilities

in Occupied Crimea

By March-April 2014, the Bastion mobile coastal defence missile systems capable of engaging not just ships but also land targets had been already stationed on the Crimean coast. Each Bastion with Oniks cruise missiles can provide coastal defence for more than 600 km of coast.

In addition, in March-April 2014, Russia transferred to Crimea the Bal coastal defence missile system, formerly stationed in the Caspian Sea. The squadron of these coastal defence missile systems was relocated to Sevastopol and included in the newly formed 15th Separate Coastal Missile Brigade. The Bal is a mobile system that carries two types of anti-ship missiles: the Kh-35E with a range of 120 km and Kh-35V – 260 km. The system is intended for control of territorial waters.

The Bal and Bastion-P coastal defence missile systems are deployed in the Reservne village area between Sevastopol and Balaklava. The Bastion-P (K300P), a mobile variant of the MZKT-7930 system on chassis, can be equipped with nuclear warhead missiles.

On 9 May 2014, the mobile coastal defence missile systems Bal and Bastion-P took part in the Victory Day military parade in Sevastopol.

In May-June 2014, according to the sources of our Monitoring Group, echeloned air defence systems, which included the mobile surface-to-air missile/anti-ballistic missile system S-400 (long-range) and the medium-range surface-to-air missile and anti-aircraft artillery system Pantsir-SlM, were deployed near Feodosiia. The information was also confirmed by the National Security and Defence Council (NSDC) of Ukraine.

In November 2014, according to our sources, the first mobile short-range ballistic missile systems Iskander-M appeared in occupied Crimea.

On 20 May 2015, the Secretary of the NSDC of Ukraine, Oleksandr Turchynov, stated that "10 Iskander-Ms were delivered to the occupied peninsula" and placed in the vicinity of Shcholkine and Krasnoperekopsk, and that Russia was also preparing to place similar systems in the Dzhankoy and Chornomorske areas. In addition, according to the NSDC Secretary, three Iskander-K battalions, including those equipped with nuclear warhead missiles, will be part of the force.

Oleksandr Turchynov also said that the Russian Federation was planning to deploy in Crimea a regiment of the Tu-22M3 bombers equipped with the new modification of the guided bombs and the Kh-15 (in the future – Kh-102) hypersonic aero-ballistic missiles.

Immediately after the occupation of Crimea in 2014, the Soviet-time Utes coastal defence missile system, which was part of the Ukrainian Navy, was restored and reactivated. The system is located in the Balaklava district of Sevastopol, in the Cape Aya area.

In 2014, pop-up launches were carried out. Since 25 April 2016, the Utes missile system has annually fired the 1982 Progress anti-ship missiles, an upgraded version of the Soviet P-35 anti-ship missile, with the range of up to 460 km. The missile is equipped with a 560-kilogramme high-explosive warhead or a nuclear warhead of up to 20 kilotonnes.

On 25 April 2017, Utes fired a cruise missile at a seaborne target. The P-35 missile successfully hit the target ship, which was set adrift in the sea at a distance of about 170 km. It was planned that by 2020, the Utes system would be replaced by the first silo-based coastal defence missile system "Bastion-S" (up to 36 Oniks missiles). As of 1 July 2021, no such replacement has taken place. However, Russian sources confirm that these plans have not been abandoned.

At the end of 2015, a significant increase in the number of the Russian Black Sea Fleet ships and their combat power began.

In 2015, the Black Sea Fleet received two new 06363 missile submarines and two new 21631 small-size missile ships (corvettes). All the four new vessels are equipped with the Kalibr cruise missiles with a range of up to 2,500 km, capable of carrying a nuclear warhead.

- On 28 September 2015, the first of the six new 636.3 submarines, the B-261 submarine Novorossiysk with the Kalibr cruise missiles, arrived in Sevastopol.

- On 18 November 2015, two new missile ships equipped with the Kalibr cruise missiles – the small-size missile ships (corvettes) Zelenyy Dol and Serpukhov – followed.

- On 25 December 2015, the second of the six new 636.3 submarines – the B-237 Rostov-na-Donu submarine with the Kalibr cruise missiles arrived in Sevastopol. On 17 November 2015, en route from the Baltic to the Black Sea, it fired cruise missiles from the eastern Mediterranean at the targets in Syria.

In 2016, two more missile ships – a frigate and a submarine – were commissioned into the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

- On 9 June 2016, Admiral Grigorovich, the main frigate in a series of six new 11356 ships, equipped with the Kalibr cruise missiles, entered Sevastopol.

- On 29 June 2016, the third of the six new missile submarines, Staryy Oskol, entered the Black Sea.

In 2017, the Russian Black Sea Fleet received two more missile frigates and three submarines equipped with the Kalibr cruise missiles. At the same time, two small-size missile ships, Zelenyy Dol and Serpukhov, were transferred from the Black Sea Fleet to the Baltic Fleet.

Table 1. New Missile Ships – Cruise Missile Carriers of the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation, as of 1 July 2021

|

The 30th Surface Ship Division (Sevastopol) |

||||||

|

|

Name |

Plant |

Laying down |

Launch |

Commis-sioning into the Black Sea Fleet |

Notes |

|

|

Admiral Grigorovich-class Project 11356Р frigates |

|||||

|

1 |

Admiral Grigorovich |

Yantar, Kaliningrad |

18.12.2010 |

14.03.2014 |

11.03.2016 |

|

|

2 |

Admiral Essen |

-«- |

08.07.2011 |

07.11.2014 |

07.06.2016 |

|

|

3 |

Admiral Makarov |

-«- |

29.02.2012 |

02.09.2015 |

27.12.2017 |

|

|

|

Project 20380 corvettes |

|||||

|

4 |

Retivyy |

Severnaya Verf, |

20.02.2015 |

12.03.2020 |

12.2021 |

Testing |

|

-- |

Strogiy |

-«- |

20.02.2015 |

12.2021 |

12.2022 |

Is being prepared for the launch |

|

The 4th Separate Submarine Brigade (Novorossiysk) |

||||||

|

|

Project 636.3 Varshavyanka (Improved Kilo-class) diesel-electric submarines |

|||||

|

1 |

Novorossiysk |

Admiraltey-skiye Verfi, |

20.08.2010 |

28.11.2013 |

22.08.2014 |

|

|

2 |

Rostov-na-Donu |

-«- |

21.11.2011 |

26.06.2014 |

30.12.2014 |

|

|

3 |

Staryy Oskol |

-«- |

17.08.2012 |

28.08.2014 |

03.07.2015 |

|

|

4 |

Krasnodar |

-«- |

20.02.2014 |

25.04 2015 |

05.11.2015 |

|

|

5 |

Velikiy Novgorod |

-«- |

30.10.2014 |

18.03.2016 |

26.10.2016 |

|

|

6 |

Kolpino |

-«- |

30.10.2014 |

31.05.2016 |

24.11.2016 |

|

|

The 41st Missile Boat Brigade, the 166th Small-Size Missile Ship Division (Sevastopol) |

||||||

|

|

Project 21631 Buyan-M-class corvettes (small-size missile ships in the Russian classification) |

|||||

|

1 |

Vyshniy Volochok

|

Zelenodolskiy Zavod |

29.08.2013 |

22.08.2016 |

28.05.2018 |

|

|

2 |

Orekhovo-Zuyevo |

-«- |

29.05.2014 |

17.06.2018 |

10.12.2018 |

|

|

3 |

Ingushetiya |

-«- |

29.08.2014 |

11.06.2019 |

28.12.2019 |

|

|

4 |

Grayvoron |

-«- |

10.04.2015 |

04.2020 |

30.01.2021 |

|

|

Project 22800 Karakurt-class corvettes |

||||||

|

(1) |

Tsiklon |

Zaliv Shipyard (Kerch) |

26.07.2016 |

24.07.2020 |

07.2021 |

Testing

|

|

(2) |

Askold

|

-«- |

18.11.2016 |

2021 |

12.2021 |

Is being prepared for the launch |

|

-- |

Amur

|

-«- |

30.07.2017 |

07.2021 |

07.2022 |

|

Thus, we can conclude that the rearmament of the Black Sea Fleet with new missile ships is reaching its final stage:

- as of 01 July 2021, there were 13 new missile ships in service (the missile salvo power – 104 cruise missiles);

- by 01.01.2022, the number of new missile ships in service will have increased by another 3, i.e. the total number will be 16 with the missile salvo power of 128 missiles;

- in 2022, it is planned to put into service 2 more ships, i.e. the total number will be 18 with the missile salvo power of 144 cruise missiles.

In addition, there is a large reserve in Russia because the new Project 22160 patrol ships provide for the possibility of installing modular container weapons, including the Kalibr or Uran cruise missiles. In August 2020, such modules were tested on the Vasiliy Bykov corvette, for which purpose the ship made the transition to the Northern Fleet (see Table 2).

Table 2. The Construction and Commissioning of Project 22160 Modular Vasiliy Bykov-Class Patrol Ships (Corvettes)

|

The 184th Sea Area Defence Ship Brigade (Novorossiysk) |

||||||

|

|

Name |

Plant |

Laying down |

Launch |

Commis-sioning into the Black Sea Fleet |

Notes |

|

1 |

Vasiliy Bykov |

Zelenodolskiy Zavod, Zaliv shipyard (Kerch)

|

26.02.2014 |

28.08.2017 |

20.12.2018 |

After the launch, on 8 November 2017, it was delivered to the Zaliv shipyard for completion. Completed on 25 March 2018. |

|

2 |

Dmitriy Rogachev

|

Zelenodolskiy Zavod |

25.07.2014 |

08.04.2018 |

11.06.2019 |

In service

|

|

3 |

Pavel Derzhavin

|

Zaliv shipyard (Kerch) |

18.02.2016 |

21.02.2019 |

27.11.2020 |

The first corvette of this type, completely built in Kerch |

|

(4) |

Sergey Kotov |

Zaliv shipyard (Kerch) |

08.05.2016 |

29.01.2021 |

12.2021 |

Is being completed afloat |

|

|

Viktor Velikiy

|

Zelenodolskiy Zavod |

25.11.2016 |

07.2021 |

12.2022 |

|

|

|

Nikolay Sipyagin

|

Zelenodolskiy Zavod |

13.01.2018 |

07.2022 |

12.2023 |

|

In case of installation of containers with cruise missiles on Project 22160 corvettes, the number of new missile ships of the Russian Black Sea Fleet will increase by 6 units and will reach 24, with the missile salvo power of 192 missiles.

Taking into account the Moskva guided-missile cruiser (the flagship of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, in service since 1983, 16 cruise missiles), the missile salvo power of the Black Sea Fleet can reach 208 missiles.

In addition to the new missile ships, during the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula, 3 new minesweepers and a new medium-size reconnaissance ship have been commissioned into the Russian Black Sea Fleet (see Table 3).

Table 3. The Construction and Commissioning of Other Warships into the Russian Black Sea Fleet

During the Occupation of the Crimean Peninsula

|

|

The 68th Sea Area Defence Ship Brigade (Sevastopol), |

|||||

|

|

Project 12700 Aleksandrit-class minesweepers |

|||||

|

|

Name |

Plant |

Laying down |

Launch |

Commis-sioning into the Black Sea Fleet |

Notes |

|

1 |

Ivan Antonov |

Sredne-Nevsky Shipyard |

25.01.2017 |

25.04.2018 |

26.01.2019 |

|

|

2 |

Vladimir Yemelyanov |

-«- |

20.04.2017 |

30.05.2019 |

28.12.2019 |

|

|

3 |

Georgiy Kurbatov

|

-«- |

24.04.2015 |

30.09.2020 |

07.2021 |

Testing |

|

|

The 519th Separate Reconnaissance Ship Division |

|||||

|

|

Project 18280 Reconnaissance Ship |

|||||

|

|

Ivan Khurs |

Severnaya Verf |

14.11.2013 |

16.05.2017 |

18.06.2018 |

|

In general, we can draw the following conclusion: the programme of rearmament of the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation with the newest missile ships, which had priority over other Russian fleets, is mostly coming to an end. Russia began to strengthen with such ships its other fleets: the Baltic, North, and Pacific ones.

In parallel with the Black Sea Fleet renewal and the strengthening of the coastal missile capability on the Crimean Peninsula, in 2014, Russia began to transform Crimea into a significant military-industrial production and service base – shipbuilding, ship repair, aircraft repair – based on trophy Ukrainian enterprises.

The Crimean Military-Industrial and Service Base

of the Occupying Force Grouping

As early as 4 April 2014, at an ad hoc meeting of the Collegium of the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu announced his intention to provide the industry of the occupied peninsula with state defence orders, emphasizing the importance of "using the manufacturing and technological capabilities of the Crimean defence industry effectively."

In mid-April 2014, Russia's Kommersant reported that the Ministry of Defence had already compiled the list of 23 Crimean enterprises of interest to the agency. Citing sources in the ministry, the newspaper wrote that "it has been done in line with the directives of President Vladimir Putin and the process is being supervised by Deputy Defence Minister Yuri Borisov. Currently, the proposals on the effective use of the enterprises are being developed."

According to Borisov himself, they "will start working on ensuring the workload for the enterprises after finalizing all the formal procedures, such as licensing and re-registration."

The "formal procedures" the Russian Deputy Defence Minister referred to meant, first and foremost, the expropriation of Ukrainian public and private enterprises. All the peninsula's defence enterprises were "nationalized" by Russia in the first months of the occupation of Crimea and most of the state-owned defence enterprises – in the first two weeks.

Almost all Crimean defence enterprises have already been or are about to be taken over by large Russian corporations, have been leased to Russian companies, or, at least, have so-called "supervisors" in Russia.

The institute of such supervisors was officially introduced in 2016 when the Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Russian Federation ordered that the Crimean enterprises should be assigned supervision. The responsibility of the supervisors has been to share work orders with the Crimean plants they supervise and ensure their modernization.

At year-end 2015, Crimea was declared "the leader in terms of the growth rate of industrial production" in Russia, with a growth of 12.4%. According to official data, in the first half of 2016, the industrial production index in Crimea exceeded 120%, which represented a 20% year-on-year increase.

The towing operation of the unfinished Kozelsk missile corvette from the More shipyard in occupied Crimea, the Don River, Rostov-on-Don, 21 October 2019. Photo from the BlackSeaNews archive

That growth was mainly due to the provision of Crimean enterprises with military orders.

In April 2016, the then Russian President's envoy in the so-called "Crimean Federal District," Vice Admiral Oleg Belaventsev, said that the military-industrial complex, which included about 30 companies, was a strategic direction for Crimea's industrial policy.

In 2016, of the eight regions of the Southern Federal District, the highest growth rate of industrial production was shown by Sevastopol. Over the course of the year, the city's output of industrial production increased by 21.8%. As a reminder, in 2014, industrial production in Sevastopol grew by 372.9%.

Overall, compared to 2015, in 2017, the defence industry output in Crimea and Sevastopol grew by 430.8% and compared to 2016 – by 227.6%.

Official data show that until mid-2018, the growth rate of industrial production in Sevastopol was a staggering 110%.

According to representatives of the Crimean "government," the Crimean enterprises are receiving a sufficient number of state orders mainly due to the personal attention of President Putin and "the firm decision to place a large number of orders at the Crimean shipyards."

As a result of the occupation, the aggressor acquired 13 Ukrainian defence enterprises, which had been part of the Ukrainian state-owned Ukroboronprom concern, as "war trophies."

One of the prototypes of the helicopter-carrying amphibious assault ships of the Russian Navy laid down at the seized Zaliv shipyard in Kerch. Photo by Artem Tkachenko, de.wikipedia.org

At the beginning of 2014, the Ukroboronprom concern included 13 Crimean enterprises, namely:

- Feodosiia Shipyard More;

- the State Enterprise Feodosiiskyi Optychnyi Zavod (Feodosiia Optical Plant);

- PAT Zavod Fiolent (Fiolent Plant), Simferopol;

- the State Enterprise Konstruktorsko-Tekhnolohichne Biuro Sudokompozyt (Sudokompozyt Design and Technology Bureau), Feodosiia;

- the State Enterprise Naukovo-Doslidnyi Instytut Aeropruzhnykh System (Research Institute of Aeroelastic Systems), Feodosiia;

- the State Enterprise Yevpatoriiskyi Aviatsiinyi Remontnyi Zavod (Yevpatoriia Aviation Repair Plant);

- the State Enterprise Sevastopolske Aviatsiine Pidpryiemstvo (Sevastopol Aircraft Enterprise);

- the State Enterprise Feodosiia Ship and Mechanical Plant of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine;

- the State Enterprise Central Design Bureau Chornomorets, Sevastopol;

- the State Enterprise Spetsialna Vyrobnycho-Tekhnichna Baza Polumia (Special Production and Technical Base Polumia), Sevastopol;

- the State Enterprise Research Centre Vertolit, Feodosiia;

- the State Enterprise Konstruktorske Biuro Radiozviazku (Radiocommunications Design Bureau), Sevastopol.

Of those 13, ten enterprises continue operations as separate entities.

- By decree 118 dated 28 February 2015, the occupation authorities of Sevastopol "nationalized" Konstruktorske Biuro Radiozviazku and unofficially liquidated it shortly thereafter.

- Skloplastyk has become part of Feodosiia Shipyard More, which after corporatization will become part of Kalashnikov Concern.

- Sevastopol Central Design Bureau Chornomorets has ceased to exist, having become a design centre within DUP Sevastopolskyi Morskyi Zavod (Sevastopol Shipyard).

The Monitoring Group of the Black Sea Institute of Strategic Studies and BlackSeaNews has identified 59 Russian companies that collaborate with the seized Crimean enterprises of Ukroboronprom and a total of 149 companies collaborating with the Crimean plants on military production.

Some of the most striking examples of the use of the trophy Crimean enterprises are provided below.

Shipbuilding

Leningrad Shipyard Pella first became a so-called supervisor and then a leaseholder of Feodosiia Shipyard More owned by the state of Ukraine (the city of Feodosiia, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea). After the occupation of Crimea, the More shipyard was seized, expropriated, and "transferred" into the federal ownership of Russia. On 15 November 2016, the More shipyard was leased to Leningrad Shipyard Pella until the end of 2020.

The Russian Pella shipyard has built three new Project 22800 (codenamed Karakurt) inner maritime zone missile corvettes, small-size missile ships according to the Russian classification, at the More shipyard.

Even before the lease of the More shipyard, on 10 May 2016, the Pella shipyard started building Shtorm, the first in a series of 3 missile corvettes of the new Project 22800 Karakurt, for the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation as part of the Russian state defence contract.

On 17 March 2017, the shipyard began the construction of Okhotsk, the second missile ship in that series, and on 19 December 2017 – Vikhr, the third corvette.

Following the publication of this information in June 2018, there was a threat of U.S. and EU sanctions against the Pella shipyard.

Afterwards, events unfolded as follows.

- The first of the three "Feodosiia Karakurts," the Kozelsk small-size missile ship, yard number 254 (during laying down it was named Shtorm), was laid down on 10 May 2016. It was scheduled to be commissioned into the Black Sea Fleet in 2019 and was launched on 9 October 2019 in an unfinished condition.

- The Okhotsk small-size missile ship, yard number 255 (during laying down it was named Tsiklon), was laid down on 17 March 2017. It was scheduled to be commissioned into the Black Sea Fleet in 2019 and was launched on 29 October 2019.

- The Vikhr small-size missile ship, yard number 256 (the name was given during laying down and so far has not been changed), was laid down on 19 December 2017 and launched on 13 November 2019.

After that, in order to avoid international sanctions, Leningrad Shipyard Pella decided to suspend the construction of the three missile corvettes of the Karakurt Project immediately, a year before the lease term expired. It launched unfinished hulls of varying degrees of readiness and organized their towing to the Pella shipyard.

AO Zelenodolskiy Zavod Imeni A. M. Gorkogo (Zelenodolsk Shipyard Plant named after A.M. Gorky), based in the Republic of Tatarstan, part of the AO Ak Bars Holding company, is one of the largest ship manufacturers in Russia. Zelenodolsk Shipyard Plant's main "success" on the peninsula is its illegal seizure of the property of the Zaliv shipyard in Kerch in August 2014.

The cable layers and icebreakers Volga and Vyatka. The displacement is over 10,000 tonnes, length −140 metres; removed from the dry dock of the Zaliv shipyard to make room for the construction of the helicopter-carrying amphibious assault ships, 18 August 2020. Photo from the BlackSeaNews Monitoring Group archive

The launch of the Tsiklon corvette, the first of the three missile corvettes of the Karakurt Project being built at the seized Zaliv shipyard in Kerch. 24 July 2020. Photo from the BlackSeaNews archive

It should be pointed out that Zaliv has one of the largest shipbuilding docks in Europe. 364 metres long and 60 metres wide, the dock has no equivalents in the RF. Therefore, we anticipate that its use for the needs of the Russian military will continue to grow.

The programme to construct warships for the Black Sea Fleet of the RF at the Zaliv shipyard as part of the Zelenodolsk Shipyard Plant's state defence order was as follows.

Three Off-Shore Maritime Zone Missile Corvettes of Project 22160

- The main ship of this project, Vasiliy Bykov, was laid down on 26 February 2014 in Zelenodolsk and launched in August 2017. In November 2017, it was towed for completion to the Zaliv shipyard. The construction was completed in March 2018. On 25 March 2018, it headed from Kerch to Novorossiysk for state testing. In December 2018, it was commissioned into the Black Sea Fleet of the RF.

- The missile corvette Pavel Derzhavin was laid down on 18 February 2016 and launched on 21 February 2019. In April 2019, it arrived in Novorossiysk from Kerch for state testing. It was commissioned into the Black Sea Fleet of the RF on 27 November 2020. It has become the first warship to be built entirely at the Zaliv shipyard.

- The missile corvette Sergey Kotov was laid down on 8 May 2016. Its launch scheduled for 2019 did not take place. The deadline for the completion of construction in 2020 was also missed. It is scheduled to be commissioned in December 2021.

The Construction of Three Missile Corvettes of Project 22800 Karakurt

- The Tsiklon corvette was laid down on 26 July 2016 and launched on 24 July 2020. The deadline for the construction completion in 2019 was missed. As of July 2021, it was being tested.

- The Askold corvette was laid down on 18 November 2016. It is currently under construction on open slipways. The deadline for the construction completion in 2019 was missed. As of July 2021, it was being prepared for the launch.

- The Amur corvette was laid down on 30 July 2017. It is currently under construction on open slipways. The deadline for the construction completion in 2020 was missed. As of July 2021, the launch was scheduled for December 2021 and the commissioning into the fleet – for December 2022.

The Construction of Naval Cable Ships of Project 15310 Codenamed Kabel

- The cable layers and icebreakers Volga and Vyatka of Project 15310 were laid down on 6 January 2015 and launched on 18 August 2020. They have the displacement of over 10,000 tonnes, deadweight of 8,000 tonnes, length of 140 metres, and width of 19 metres. Their purpose is laying marine communications cables, wiretapping or damaging international submarine cables, including in Arctic waters. Contract deadlines for the completion of construction in 2018 and 2019 were missed.

The Construction of Two Military Oil Tankers (Supply Ships) of Project 23131

- Their purpose is receiving, storing, transporting, and transferring liquid (diesel fuel, motor oil, water) and dry cargoes (food, equipment, weapons) to ships.

- The length of one such ship is 145 m, width – 24 m, water draught – 7 m, speed – 16 knots, deadweight – 12,000 tonnes, navigation area – unlimited, cruising endurance – 8,000 miles. The ships were laid down on 26 December 2014. The deadlines for construction completion in 2017-2018 were missed due to Western sanctions. The formation of the ships' hulls and superstructures has been completed. The preparation of the hulls for electrical installation work is currently underway.

The geography of manufacturing ties of enterprises from the regions of the RF with the seized Crimean enterprises manufacturing and carrying out maintenance of military equipment

The Construction of Amphibious Assault Ships of Project 23900

On 20 July 2020, for the first time in the history of the Russian Navy, two helicopter-carrying amphibious assault ships of Project 23900, Ivan Rogov and Mitrofan Moskalenko (yard numbers 01901 and 01902), were laid down at the seized Zaliv shipyard with the participation of the President of the Russian Federation.

The operational characteristics and even the general appearance of these ships are classified.

- It is known that one such ship will carry on board more than 20 heavy-lift helicopters, as well as ship-based unmanned combat aerial vehicles and reconnaissance UAVs, will have a well dock for landing craft utilities, and will be able to carry about 1,000 marines and 75 armoured fighting vehicles. Its displacement is up to 30,000 tonnes, length – over 220 m. The cost of one such ship is 40 billion roubles. The commissioning of the first amphibious assault ship into the Russian Fleet is scheduled for 2028, the second – for 2029. As of 1 July 2021, it was known that the formation of the hulls of both ships began.

- Note that the secrecy of this project suggests that, in fact, the Russian Federation might plan to build something more than helicopter-carrying amphibious assault ships. During the laying down of the ships, the President of the Russian Federation said: "They are good, modern. We even think – I don't know if the minister in St. Petersburg hears me now – we even planned to redo something there and use them for other purposes. Almost the same, only for different purposes. Now I will not talk about it yet." It is possible that these might be light aircraft carriers, on which not only helicopters but also vertical take-off and landing aircraft will be based.

The construction of warships of this class will require cooperation with hundreds of plants in Russia.

Aircraft-Building Enterprises

PAO Obedinennaya Aviastroiitelnaya Korporatsiya (the United Aircraft Corporation), Moscow. It is on the Ukrainian and EU sanctions lists. By the orders of the Ministry of Industry and Trade of the RF, Obedinennaya Aviastroiitelnaya Korporatsiya has been officially assigned to DUP RK Yevpatoriiskyi Aviatsiinyi Remontnyi Zavod (Yevpatoriia Aviation Repair Plant) in order to provide the latter with orders. After corporatization, Yevpatoriiskyi Aviatsiinyi Remontnyi Zavod will become part of Obedinennaya Aviastroiitelnaya Korporatsiya.

AO Vertolety Rossii (Russian Helicopters), Moscow, part of Rostec. The company is on the Ukrainian and U.S. sanctions lists. By the orders of the Ministry of Industry and Trade of the RF, Vertolety Rossii has been officially assigned to Sevastopolske Aviatsiine Pidpryiemstvo (Sevastopol Aircraft Plant) in order to provide the latter with orders. FGUP Syevastopolskoye Aviatsionnoye Pryedpriyatiye is de facto integrated into the Vertolety Rossii holding.

AO Tekhnodinamika, Moscow, part of Rostec. The company is on the Ukrainian and U.S. sanctions lists. It is a leading Russian developer and manufacturer of aircraft equipment, including landing gear, fuel and flight control systems, and auxiliary power units. Tekhnodinamika has been assigned to Naukovo-Doslidnyi Instytut Aeropruzhnykh System in order to provide the latter with orders. After the corporatization of the State Enterprise Naukovo-Doslidnyi Instytut Aeropruzhnykh System, the company will become part of AO Tekhnodinamika.

PAO Taganrogskiy Aviatsionnyy Nauchno-Tekhnicheskiy Kompleks Imeni G. M. Berieva (Taganrog Aviation Scientific-Technical Complex named after G. M. Beriev), Taganrog. The company develops and manufactures aviation equipment, part of PAO Obedinennaya Aviastroiitelnaya Korporatsiya. The seized Yevpatoriiskyi Aviatsiinyi Remontnyi Zavod repairs Be-12 aircraft produced by PAO Taganrogskiy Aviatsionnyy Nauchno-Tekhnicheskiy Kompleks Imeni G. M. Berieva that oversees the quality of repairs.

AO 121 Aviatsionnyy Remontnyy Zavod (121 Aircraft Repair Plant) is a leading enterprise in repairing and modernizing tactical aviation aircraft and engines. The company is part of PAO Obedinennaya Aviastroiitelnaya Korporatsiya. A separate business unit of 121 Aviatsionnyy Remontnyy Zavod, Service Centre Saki, has been set up on the premises of Yevpatoriiskyi Aviatsiinyi Remontnyi Zavod in Novofedorivka.

As of 1 July 2021, we can assume that the formation of a military-industrial base on the Crimean Peninsula to serve the needs of the occupying force of Russian troops is almost completed.

Taking into account the fact that the programme of Russia's Black Sea Fleet renewal has been largely completed, we can conclude that the focus area of this military-industrial base will be repair and maintenance of Russia's Black Sea Fleet ships.

An exception to this main specialization is the construction in Kerch of the two large amphibious assault ships with an air wing (helicopters, UAVs, vertical take-off and landing aircraft).

Areas of specialization such as repair and maintenance of military aircraft, helicopters, air defence missile systems, and coastal cruise missiles will be much narrower in scope but not less important.

The Restoration of the Crimean Nuclear Infrastructure

The Monitoring Group believes there is a high probability that since 2015-2016, there have already been nuclear warheads for sea-based and coastal missile systems in Crimea.

In March-April 2014, in the early days of the occupation, Russian troops took control of the nuclear weapons storage and maintenance facilities on the territory of the Crimean Peninsula, left there from the Soviet times.

In May 2014, the Russian command inspected the main nuclear weapons storage and maintenance facility Feodosiia-13.

On 26 January 2015, Russian media reported that as part of the deployment and build-up of the Russian military force grouping in Crimea, a new body was created within the 12th General Directorate of the General Staff of the Russian Ministry of Defence, whose mission would be the storage, transportation, and disposal of nuclear units of tactical and ballistic missiles.

On 25 April 2015, the Information and Analytical Centre of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine announced that on 23 April 2015, the Consulate General of Ukraine in Rostov-on-Don had received a notification that several railroad cars with the "Nuclear danger" sign on board travelled via the Rostov railway station, presumably towards the Crimean Peninsula. According to the peninsula residents, such cargoes had been seen on the territory of occupied Crimea on numerous occasions.

Currently, Russia is restoring the main Crimean nuclear weapons maintenance facility, previously one of the central USSR nuclear weapons storage bases – military object No. 62047, also known as Feodosiia-13, in Kyzyltash (Krasnokamianka), in the mountain tract between Sudak and Koktebel.

Note. The Feodosiia-13 facility became operational in 1955 and was used to store nuclear ammunition for aviation, artillery, and missiles, including for the warships of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet. The atomic bombs used in the September 1956 tests at the Semipalatinsk range had been assembled at that site. In 1959, the first nuclear warheads in the GDR (Furstenberg) were received from Kyzyltash. In September 1962, during the Caribbean crisis, six aircraft bombs assembled in Kyzyltash were sent to Cuba as part of Operation Anadyr. Prior to the occupation of Crimea in 2014, the complex of buildings and structures was used as a permanent deployment base of the 47th Special Operations Regiment Tyhr of the Internal Troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, which consisted of two special operations battalions. The commandant’s office of the guard of the 51st consolidated depot of the Ukrainian Naval Forces and a patrol battalion were also stationed there.

Russia's Military Contingent in Occupied Crimea

The maritime component of Russia's force in Crimea includes surface and submarine forces of the Black Sea Fleet. The surface forces include an attack force (artillery and missile ships), an amphibious force (large and small amphibious ships), and sea area defence (anti-submarine ships and minesweepers).

The maritime component of Russia's force in Crimea is comprised of:

- the 30th Surface Ship Division;

- the 197th Amphibious Ship Brigade;

- the 41st Missile Boat Brigade;

- the 68th Sea Area Defence Ship Brigade;

- the 4th Submarine Brigade;

- the 519th Separate Reconnaissance Ship Division;

- the 176th Separate Oceanographic Research Vessel Division;

- the 205th Supply Ship Detachment;

- the 145th Rescue Boat Detachment;

- the 58th Supply Vessel Group (Feodosiia).

In addition, the Black Sea Fleet includes:

- the 115th Security And Service Commandant’s Office;

- the 184th Experimental Research Base;

- the Mine And Countermine Base;

- the Missile And Artillery Weapons Repair Facility;

- the 13th Ship Repair Facility;

- the 91st Ship Repair Facility;

- the 17th Naval School of Junior Specialists;

- the Black Sea Higher Naval School;

- Sevastopol Presidential Cadet School.

The land component of Russia's force in Crimea is comprised of:

- the 810th Separate Marine Corps Brigade (Sevastopol);

- the 126th Separate Coastal Defence Brigade (Perevalne; the Simferopol district);

- the 15th Separate Coastal Missile Brigade (Sevastopol);

- the 127th Separate Intelligence Brigade (Simferopol);

- the 1096th Anti-Aircraft Missile Regiment (Sevastopol);

- the 8th Artillery Regiment (Simferopol);

- the 68th Separate Marine Engineering Regiment (Yevpatoriia);

- the 4th CBR Defence Regiment (Sevastopol);

- the Airborne Assault Battalion of the Airborne Forces (Dzhankoy);

- the 56th Airborne Assault Regiment (Feodosiia).

At the end of 2016, in order to manage the coastal units and tactical formations, the 22nd Army Corps of the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea was formed.

The 22nd Army Corps now includes the Black Sea Fleet's coastal defence troops, which previously reported to the Black Sea Fleet Deputy Commander for Coastal Defence.

Note. An army corps is a combined-arms formation of the ground forces of the Russian Federation, formed for solving operational-tactical tasks. An army corps may include two-four or more divisions. Since a division in the Armed Forces of the RF has upward of seven thousand servicemen, an army corps can include tens of thousands of troops.

The air defence of occupied Crimea is provided by the 31st Air Defence Division of the 4th Air and Air Defence Forces Army, whose units are stationed in:

- Sevastopol (the 12th Anti-Aircraft Missile Regiment);

- Feodosiia (the 18th Anti-Aircraft Missile Regiment);

- Yevpatoriia (an anti-aircraft missile regiment);

- Dzankoy (the northern Crimea) – since 2018.

In 2017, the anti-aircraft missile regiments in Sevastopol and Feodosiia were rearmed with the latest S-400 systems that had replaced the S-300 ones.

The air component of the Russian Military Force in Crimea includes the units of the bomber, ground-attack, fighter, and army aviation that comprise the 4th Air and Air Defence Forces Army and the Black Sea Fleet Naval Aviation.

The Black Sea Fleet Naval Aviation consists of:

- the 43rd Separate Naval Assault Aviation Regiment (Saki);

- the 318th Separate Composite Aviation Regiment (Kacha).

In addition to naval aviation, a new aviation tactical formation – the 27th Composite Aviation Division – composed of three different types of regiments has been formed in Crimea:

- the 37th Composite Aviation Regiment (Hvardiiske);

- the 38th Fighter Aviation Regiment (Belbek);

- the 39th Helicopter Regiment (Dzhankoy).

This air grouping is capable of performing combat missions throughout the entire depth of the Black Sea region. It received new Su-30SM fighters (in January 2015), modernized Su-27SMs, Su-24M attack aircraft, and Su-25SM ground-attack aircraft. In addition, the 39th Helicopter Regiment is equipped with the type Ka-52, Mi-28N, and Mi-8 AMTSh helicopters.

In 2017, due to the approaching Kerch Bridge construction deadline, the formation of the bridge naval guard brigade began within Russia's National Guard.

As of 1 July 2021, the 115th Separate Special Operations Brigade is based in the occupied Crimean city of Kerch.

It includes the 39th Rosgvardiya Naval Detachment, the Rosgvardiya regiment, and other special units of up to 900 persons. In 2018, the 39th Naval Detachment received 4 Grachonok-type anti-sabotage boats of Project 21980, in 2019 – 4 new BK-16 landing craft utilities of Project 02510 and 8 Sargan speedboats produced at the seized Crimean More shipyard.

Aerospace forces

Also in 2017, Russia started a technical re-equipment of the seized Ukrainian Space Flight Control Centre in Yevpatoriia.

The Centre has one of the world's largest fully steerable telescopes, 70 metres in diameter. The Centre is now included in the Russian Space Forces as the 40th Separate Command and Measurement Complex (Deep Space Communications Centre) of the The Titov Main Test and Space Systems Control Centre.

The Space Flight Control Centre in Yevpatoriia has become part of the Russian GLONASS system. The Centre is equipped with the Russian command and measurement system with a range of up to 40,000 km and is involved in the control of all Russia's orbital space force.

Another 2017 decision was to deploy in Crimea the fixed early-warning radar Voronezh-SM with the detection range of up to 6 thousand km. It will be located in Sevastopol's Khersones Cape in 2024.

The Size and Composition of the Force Grouping in Crimea

On 14 January 2017, Metropolitan Platon of Kerch and Feodosiia blessed the S-400 Triumph, the new anti-aircraft missile system of Russia's Armed Forces. Photo: black-drago.livejournal.com

On 14 January 2017, Metropolitan Platon of Kerch and Feodosiia blessed the S-400 Triumph, the new anti-aircraft missile system of Russia's Armed Forces. Photo: black-drago.livejournal.com

In the Soviet era, about 100 thousand troops and 60 thousand civilian personnel were stationed on the Crimean Peninsula.

Before the occupation of Crimea, under the agreement with Ukraine, there had been 12.5 thousand servicemen of the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation with an authorized number of up to 25 thousand people.

At the beginning of 2017, the Monitoring Group estimated the size of the Russian armed forces in occupied Crimea at close to 60 thousand people with the prospect of increasing up to 100 thousand people. By comparison, according to the U.S. Department of Defence, all American bases in Japan have a total of about 50 thousand servicemen stationed there.

On 6 March 2015, at the Atlantic Council and Freedom House in Washington, D.C., the Monitoring Group presented a report Human Rights Abuses in Russian- Occupied Crimea.

In particular, the report said: "Putin is turning the entire territory of Crimea into an enormous military base at an incredible pace. According to our estimates, it will be staffed by about 100,000 people." The forecast was based on the official press release of the Southern Military District of Russia's Ministry of Defence of 17 September 2014 entitled The Newly Formed Military Units of the Southern Military District in Crimea Will Receive New Regimental Colours.

The report said: "By the end of this year, more than 40 tactical formations and military units of the Southern Military District (SMD) will be granted the newly designed regimental colours. Most of the military units of the SMD where the ceremonies of regimental colours award will take place are the recently formed in Crimea aviation, air defence, engineering, artillery, and CBR Defence regiments, separate brigades of coastal defence troops, technical support, and so on."

In the Armed Forces of the RF, regimental colours are awarded to military units (a regiment, a separate battalion) and tactical formations (a brigade, a division, an army). The manpower of the regiment in Russia is between 2,000 and 3,000 servicemen – soldiers, sergeants, praporshchiks (equivalent to warrant officer class 1), and officers – and civilian personnel, while a brigade consists of up to 3,000-4,000 personnel.

On 8 June 2015, during a speech at the meeting of the Ukraine-NATO Interparliamentary Council in Kyiv, the Ukrainian Defence Minister, Stepan Poltorak, said: "The Russian Federation is increasing the size of its force grouping in Crimea. Now it includes about 24 thousand servicemen... There is a high probability of the deployment of strategic nuclear weapons carriers on the peninsula. In fact, Russia is forming a powerful force in Crimea to ensure its grip on the occupied territory and defend its interests in Ukraine and other states." According to him, if such build-up of force continued, it was possible that by 2017, Russia could double the number of its troops and create a powerful contingent of 43 thousand personnel.

On 30 June 2016, during a visit to Bulgaria, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko said in an interview to Bulgarian television, "More than 60,000 Russian military personnel are located on the Crimean Peninsula, and there is a great threat of the deployment of nuclear weapons there."

At the end of February 2018, Deputy Defence Minister Anatoly Petrenko said that if in 2013, the number of Russian military personnel in Crimea was about 12 thousand, in 2018, it exceeded 31 thousand.

Finally, during Russia's deliberate military escalation and show of force on the borders of Ukraine and in occupied Crimea in April-May 2021, the transfer of new army units, planes and ships to the peninsula was repeatedly recorded, and there were reports of a significant increase in the number of troops in occupied Crimea. However, the official data of the Ukrainian authorities regarding their number remained at the level of 31-32 thousand people.

Thus, the actual number of Russian troops in occupied Crimea remains a matter of debate.

NATO's Black Sea Dilemma

The missile capabilities and means of delivery concentrated on the territory of occupied Crimea have led to a major change in the military-strategic balance in the Black Sea region, as well as in the Black Sea-Mediterranean and Black Sea-Caspian regions, in favour of the Russian Federation.

Prior to the first military use of the ship-launched Kalibr cruise missiles on 7 October 2015, their range was believed to be around 300 km. But during the first tactical employment in Syria, the missiles struck targets at distances of over 1,500 km. Some data suggest, however, that the true range of these missiles can be up to 2,600 km.

On 22 October 2016, the head of the combat training department of the Russian Navy Main Staff, Rear Admiral V. Kochemazov, said that the ship-launched cruise missiles Kalibr had a shooting range of up to 2,000 kilometres. "Depending on the targets – whether they are ground or sea ones – and on the track, taking into account the need to bypass obstacles on the ground, the range of these missiles is up to 2 thousand kilometres." The specialist websites state that the range of these missiles is 2,600 km. Thus, from the Sevastopol area, the Kalibr missiles of Russia's Black Sea Fleet, at a minimum, are capable of reaching targets located in all European countries, except Norway, Great Britain, and Spain, as well as in North Africa and the Middle East.

The mobile coastal defence missile system Bastion with the Oniks cruise missile, in the same manner as Kalibr, is capable of striking not only ships but also pinpoint land targets. Its range is likely to be 600 kilometres. When fired from the Sevastopol area, Bastion can strike land targets in the coastal areas of all Black Sea countries. It can also be used with a nuclear warhead.

Officially, the mobile short-range ballistic missile system Iskander has approximately the same range of 500 kilometres and can carry a nuclear warhead of up to 50 kilotonnes. However, many experts believe that the declared range is purposely underestimated to conceal the violation of the INF Treaty and that the real range of this cruise missile is 2,000-2,600 km.

The air regiment consisting of 16 Tu-22 M3 missile-carrying bombers is scheduled for deployment in Crimea. Each aircraft is able to carry 10 Kh-101 (Kh -102) cruise missiles with a range of about 5,000 km, including a nuclear warhead of 250 kilotonnes.

The Kh-101 (or Kh-102 with a nuclear warhead) is a strategic air-to-surface cruise missile with radar-evading stealth features. The test results have demonstrated a circular error probable (CEP) of 5 m at a range of 5,500 km. It is capable of destroying moving targets with up to 10 metres accuracy.

Overall, coupled with the plans to deploy the Tu-22M3 missile bombers, the coastal missile systems Iskander and Bastion and the Black Sea Fleet Kalibr sea-launched missiles stationed on the occupied Crimean Peninsula now threaten not only the entire Black Sea coast, as previously believed, but also the whole Europe, especially on its southern flank.

So, in 2014-2021, the military-strategic significance of the Crimean Peninsula for Russia has increased considerably, and the process continues. It accelerated even more after the completion of the Kerch Bridge due to the radical improvement of the logistics.

As a result, the military capabilities of the Crimean Peninsula, including the offensive one, will represent a new and unique phenomenon. That is further exacerbated by the fact that in 2017-2018, Turkey's relations with NATO, the EU, and the USA worsened, while with the RF – improved to the point that Turkey purchased the S-400 air defence systems from Russia and began construction of the first section of the Turkish Stream gas pipeline. All of the above leads us to the conclusion

that as a result of the militarization of occupied Crimea, Russia has accomplished an absolute military-strategic superiority in the Black Sea region, which radiates into the South Caucasus and the Middle East.

In early May 2016, during a speech at a conference of the Chiefs of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Balkan countries in Istanbul, the President of Turkey stated:

"We must strengthen coordination and cooperation in the Black Sea. We look forward to concrete results of the NATO summit in Warsaw on 8-9 July. We need to make the Black Sea a sea of stability. I have told the Secretary General of NATO: "You are not present in the Black Sea, so it has almost become a Russian lake." We must fulfil our duty as Black Sea countries. If we do not take action, history will not forgive us."

Surprising though it may seem now, in 2016, when Turkey was almost in a state of "cold war" with Russia, President Erdogan was the first among NATO countries leaders to adequately describe the situation in the Black Sea, which developed two years after the occupation and subsequent illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula by the Russian Federation.

On 8-9 July 2016, the Warsaw summit of the heads of states and the heads of governments of NATO member states was expected to make decisions on strengthening NATO's naval capabilities in the Black Sea. The initiative belonged to the Romanian government that proposed to establish a regular NATO flotilla in the Black Sea. For Romania, the issue was a top priority. In view of the occupation of Crimea and Russian aggression in the Donbas that also endangered the Sea of Azov, Ukraine certainly supported it.

However, the refusal of Bulgaria, whose prime minister said he wanted to see cruise liners and not military frigates near the Bulgarian coast, halted the idea. Moreover, a month earlier, the Bulgarian prime minister stated that "the Black Sea should be declared a demilitarized zone, without warships or submarines."

The Romanian naval initiative was launched at the end of 2015, immediately after the installation of the SM-3 AEGIS Ashore missile defence system interceptors at the U.S. Air Force base in Deveselu, 35 km from the border with Bulgaria.

Romania understood that, taking into account the formation of a Russian strike force in occupied Crimea, equipped with missiles capable of reaching any goal in Romania, the whole country was now a potential target for missile attacks not only from the air but also from the sea, i.e., from the new missile ships and submarines of the Black Sea Fleet, as well as from the territory of the Crimean Peninsula.

Occupied Crimea in the Syrian War

Since late 2015, along with Novorossiysk, occupied Crimea has become one of Russia's main lodgement areas in the Syrian war. The Russian forces in Crimea, surface ships, submarines, and marines, have been taking an active part in Russia's military actions in Syria.

In 2015-2017, the following ships of Russia's Black Sea Fleet carried out Kalibr cruise missile attacks on ground targets in Syria from the eastern Mediterranean:

- the Rostov-na-Donu submarine on 8 December 2015;

- the Zelenyy Dol corvette on 19 August 2016;

- the Serpukhov corvette on 19 August 2016;

- the Admiral Grigorovich frigate on 15 November 2016;

- the Admiral Essen frigate on 31 May 2017;

- the Krasnodar submarine on 31 May 2017;

- the Admiral Grigorovich frigate on 23 June 2017;

- the Krasnodar submarine on 23 June 2017;

- the Admiral Essen frigate on 23 June 2017;

- the Admiral Essen frigate on 5 September 2017;

- the Velikiy Novgorod submarine on 14 September 2017;

- the Kolpino submarine on 14 September 2017;

- the Velikiy Novgorod submarine on 22 September 2017;

- the Velikiy Novgorod submarine on 5 October 2017;

- the Kolpino submarine on 5 October 2017;

- the Velikiy Novgorod submarine on 31 October 2017;

- the Kolpino submarine on 3 November 2017.

Overall, as of 1 January 2019, 56 out of 100 sea-launched Kalibr cruise missiles fired by the Russian Navy in Syria belonged to ships and submarines of the RF Black Sea Fleet, while 44 other missiles were launched by the corvettes of the Russian Caspian Flotilla.

That is, as of now, 2 frigates and 4 submarines of the Russian Black Sea Fleet have combat experience of launching long-range missiles, since, as mentioned earlier, the Serpukhov and Zelenyy Dol corvettes have been transferred to Russia's Baltic Fleet.

The "Syrian Express"

In addition to carrying out cruise missile strikes, Russia supplies the Assad regime with equipment and ammunition carried from Sevastopol and Novorossiysk by large amphibious ships of the Black Sea Fleet and other Russian fleets, as well as by the Black Sea Fleet auxiliary vessels based in occupied Sevastopol – the so-called "Syrian Express."

Since late 2015, occupied Crimea has become and remains to this day one of Russia's main lodgement areas in the Syrian war. The Black Sea Fleet ships and submarines, as well as Crimean marines, are actively engaged in Syria military operations.

In October 2016, Russian Black Sea Fleet ships delivered a battalion of the Bastion coastal missile systems from Crimea to Syria. In November 2016, its replacement arrived in Crimea. In 2017, missile systems S-300, S-400, and Buk-3 were deployed in Syria in the same way.

In 2016, large amphibious ships of Russia's Black Sea Fleet conducted 67 return trips from Sevastopol and Novorossiysk to the naval base of the Russian Federation in Tartus, Syria. The ships carried missile launchers, armoured vehicles, and military vehicles.

Of the 67 trips, half (34) were made by large amphibious ships of Russia's Black Sea Fleet, 17 – by the Baltic Fleet, and 16 – by the Northern Fleet. It should be noted that in 2015, large amphibious ships of the Russian Navy completed 69 such trips with the same distribution ratio between the fleets, while in 2014 and 2013 – 46 and 30 trips respectively.

Thus, in 2015-2016, after the occupation of Crimea, the number of Russian Black Sea Fleet ships' trips to Syria doubled.

In 2017, the "Syrian Express" made 41 return trips by amphibious ships. Over 2016, auxiliary vessels − bulk carriers under the naval flag of the Russian Federation – of the 205th Supply Ship Detachment completed at least 17 return trips, while in 2017 − only 9 return trips between Sevastopol and the Syrian port of Tartus.

In 2018, the "Syrian Express" made 34 return trips, including 30 by large amphibious ships. That is, compared to 2014-2016, in 2017-2018, the RF largely relieved amphibious ships from Tartus voyages.

That happened due to the use of up to 10 large ferries leased through the specialized firm Oboron Logistics. That allowed the auxiliary fleet warships and cargo ships that were not subject to inspections to carry only weapons, ammunition, and troops under the naval flag while transporting the rest of the cargo by civilian ships.

In 2017, the Russian Federation decided to establish a full-fledged Russian naval base in the Syrian port of Tartus. From the military point of view, the Crimean Peninsula is a key element in ensuring its operation.

Earlier, in Tartus, the Russian Navy had only a small logistic support post that large ships could not enter and had to be provided for on the roadsteads. The new Tartus base will allow regular maintenance and repairs of different class ships – from minesweepers to frigates.

The Sevastopol-based 810th Separate Marine Corps Brigade of Russia's Black Sea Fleet provides on-board security for Russian ships and vessels carrying cargoes to Syria and also guards the naval base of the Russian Federation in Tartus.

It was the occupation of Crimea and the further accelerated development of the Crimean military base that made Russia's active military engagement in Syria possible. The drastically changed composition of the Black Sea Fleet became the basis of Russia's naval presence in the eastern Mediterranean.

However, the links of occupied Crimea with the Syrian regime, which are being purposefully strengthened by Moscow, go well beyond the military sphere.

As part of the Fourth Yalta International Economic Forum, held in April 2018, a cooperation memorandum between Crimea and the Syrian province of Latakia, as well as between the twin cities of Yalta and Latakia, was signed. The forum included the first Yalta conference titled The Economic Development of the Syrian Republic, with the Syrian delegation being the most numerous. The forum's press service reported the adoption of several Russian-Syrian agreements, some of which had been signed behind closed doors.

Considering the aforementioned situation and the accelerated militarization of Crimea, the authors of this report have analysed the history of NATO's naval presence in the Black Sea region – excluding the NATO Black Sea states: Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria – since 1991 and especially in 2013-2020.

The Black Sea History of NATO's Naval Forces

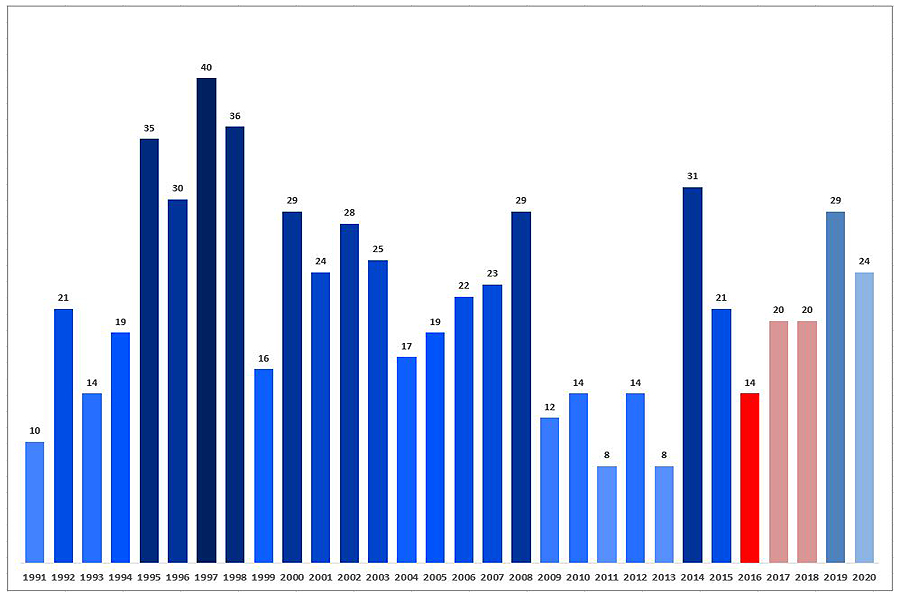

NATO Maritime Command's interest in the Black Sea reached a peak between 1992 and 1998. That was the period immediately after the collapse of the USSR when six newly independent states (Moldova, Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan) emerged in the Black Sea region, while the communist regimes came to an end in Romania and Bulgaria.

In 1995-1998, the annual number of NATO naval ship entries in the Black Sea ranged from 30 to 40 (1997 – 40, 1998 – 36, and 1995 – 35). The largest number of NATO ship entries in the Black Sea took place until the second half of the 1990s-early 2000s due to regular large-scale international naval exercises there.

From 2000 to 2007, the number of entries fluctuated between 17 and 29. Therefore, 29 entries in 2008, the year of the Russian-Georgian war, seemed high. However, in the year of the Russian aggression against Georgia, which started on 8 August 2008, the number of NATO naval ship entries in the Black Sea didn't reach the mid-1990s figures but only those of the 2000s.

Moreover, 13 out of the 29 entries occurred following August 2008, that is, after the beginning of the war, subsequently, sharply falling again.

The years 2009-2013 following the 2008 NATO Bucharest summit, which de facto denied Ukraine and Georgia a realistic Euro-Atlantic perspective, can be considered the period of NATO's loss of interest in the Black Sea. Twice during that period – in 2011 and 2013 – the number of warship visits to the area dropped to the historical low since 1991 – 8 entries, while the 2010 and 2012 maximum of 14 visits each year was lower than in any year of the preceding two decades.

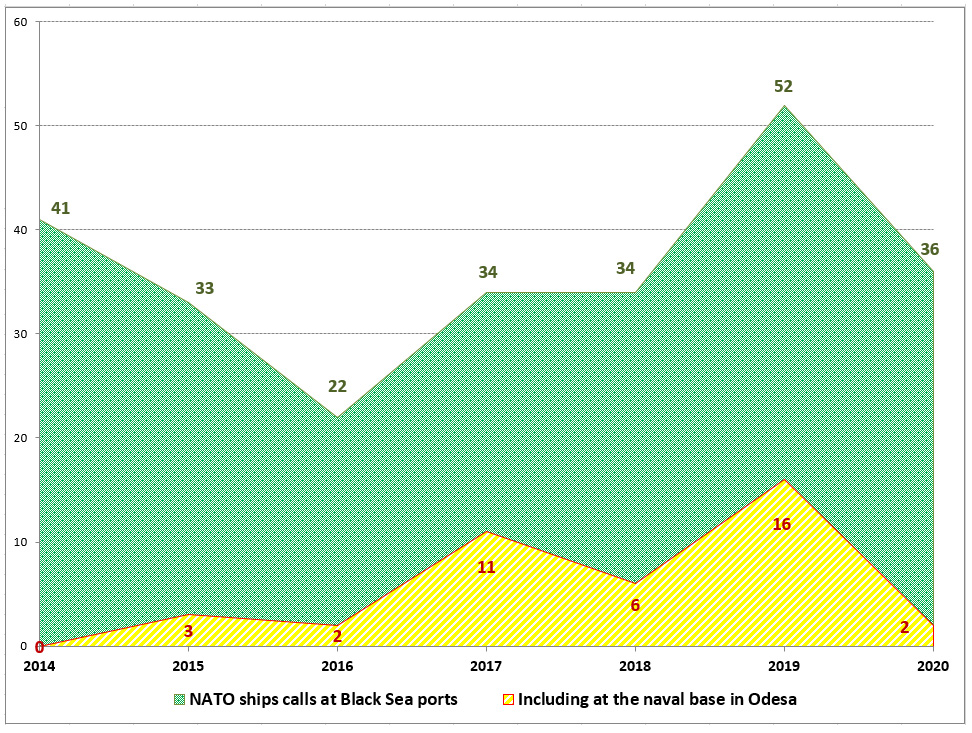

In 2013, the last year before the occupation of Crimea and the Russian aggression in eastern Ukraine, the number of NATO warship entries in the Black Sea – 8 – was not only lower than in all the previous years except for 2011 but was the lowest since the collapse of the USSR in 1991. In 5 out of 8 Black Sea entries in 2013, the ships from NATO non-Black Sea countries visited the Ukrainian ports of Sevastopol and Odesa.

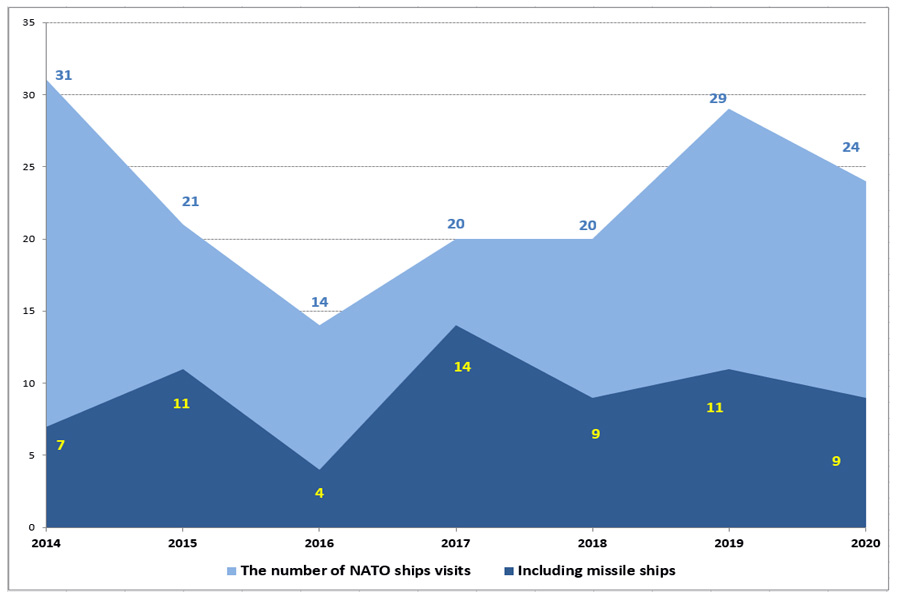

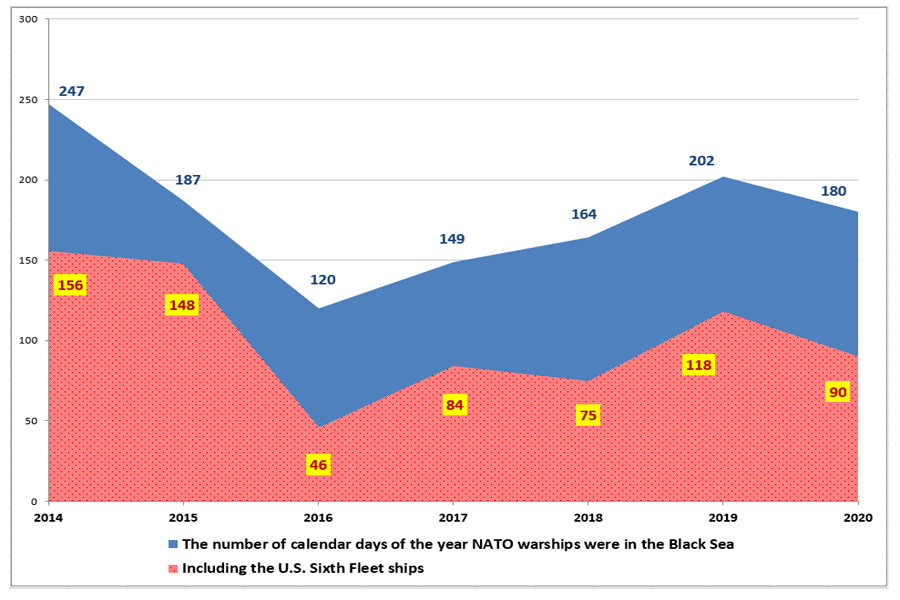

However, in 2014-2016, during the occupation of Crimea and Russia's aggression in the east of Ukraine, opening access to the Sea of Azov in view of Ukraine's loss of its Navy, the naval presence of NATO in the Black Sea became a real factor in deterring further Russian aggression against Ukraine.

That was especially important in 2014 and 2015 when the risks of Russia's Black Sea Fleet landing operations in the coastal regions of Ukraine were at an all-time high. Over those years, NATO warships were present in the Black Sea almost continuously. At the same time, in 2014, the first year of Russian aggression against Ukraine, NATO naval presence in the Black Sea was comparable to the 2008 figures during the "five-day war" between Russia and Georgia despite the totally incomparable scale. However, in the following 2 years, it dropped significantly again.

It should be noted that between 20 February and 7 March 2014, during the crucial initial phase of the Russian military special operation to occupy Crimea, which involved Russian warships, there were no combat-capable navy vessels of the non-Black Sea NATO states in the area.

A command ship and a damaged frigate of the U.S. Sixth Fleet that happened to be in the Black Sea at the time could only conduct radio-electronic intelligence and did not have any strike capability. By 7 March 2014, the day when NATO naval ships started patrolling the Black Sea, in Crimea, all the administrative buildings had already been seized by Russian troops, all access routes to the peninsula had been cut off, all ports and naval operating bases of the Ukrainian Naval Forces, and other Ukrainian military garrisons had been blocked, while the Russian military ships had already deployed in the peninsula several thousand troops and equipment, including mobile coastal anti-ship missile systems.

The analysis of Russian sources makes it clear that at the time, the Russian military command viewed the absence of NATO warships in the Black Sea as a factor that made the operation to seize Crimea possible. After all, the presence of a foreign non-allied warship in any area at the time of crisis forces any power to consider it a potential opponent, which automatically entails planning the actions of the Navy, Air Force, etc., accordingly.

That proves that not only the Ukrainian but also the U.S. and NATO military and intelligence circles did not expect or consider the Russian occupation of Crimea scenario. That has been recently confirmed by the then NATO Secretary General, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, who led the Alliance's headquarters until 1 October 2014:

"I do not think that Europe could stop the annexation. It became a surprise to all of us. We considered the Russians to be partners we could work with. But suddenly it turned out that they did not share such a view. Russia has begun a "hybrid war," combining conventional military actions with the actions of the "little green men" and an intricate information and disinformation campaign. We were really caught off-guard, and I do not think we could have done more or anything differently. So, we had to adapt to the new security situation."

Obviously, however, besides the lack of analytical forecasts and possible scenarios of Russia's actions in the Black Sea, NATO states and their naval forces lacked recent military intelligence data on the Black Sea region.