The (Un)Foreseen Storm-2 – from Crimea to Odesa. Maritime Risks in 2020: The Black Sea

Andrii KLYMENKO,

editor-in-chief of BSNews,

the Head of the Monitoring group of the Institute for Black Sea Strategic Studies.

First published in an abbreviated version in the special project of The Ukrainian Week magazine – World in 2020.

Continued. See the beginning here – The (un)foreseen storm - from Mariupol to the Bosphorus. Maritime risks in 2020: the Sea of Azov

* * *

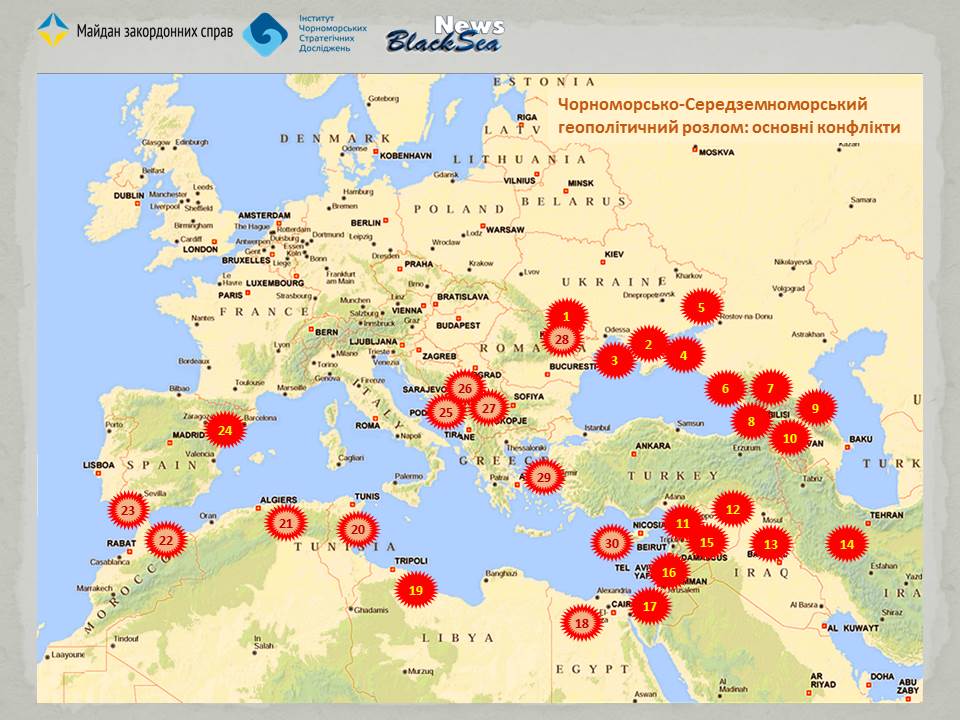

It is worth reminding that we are considering the maritime risks in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, related to possible actions of the Russian Federation, based on the experience of 2014-2019, not only in the Ukrainian-Russian but also in the macro-regional context – the Black Sea-Mediterranean.

We assume that the Russian attack on Georgia in 2008 shook, and the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 shifted the long conservation of the entire geopolitical rift – from Gibraltar to Mariupol.

We assume that the Russian attack on Georgia in 2008 shook, and the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 shifted the long conservation of the entire geopolitical rift – from Gibraltar to Mariupol.

Such tectonic shifts do not stop on their own. Especially as, according to Vladislav Surkov’s article «Putin’s long state» in the Nezavisimaya Gazeta newspaper of 11.02.2019, «Putin’s political machine is only gaining momentum and is getting ready for long, difficult, and interesting work. Its operation at full capacity is far ahead, so in many years Russia will still be a Putin’s state».

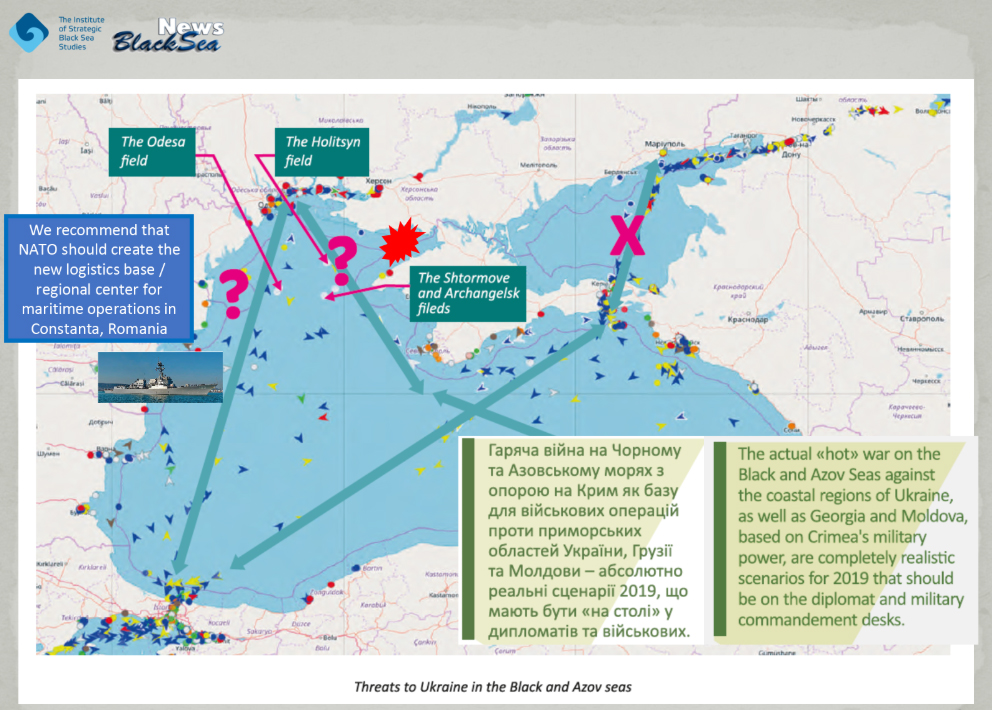

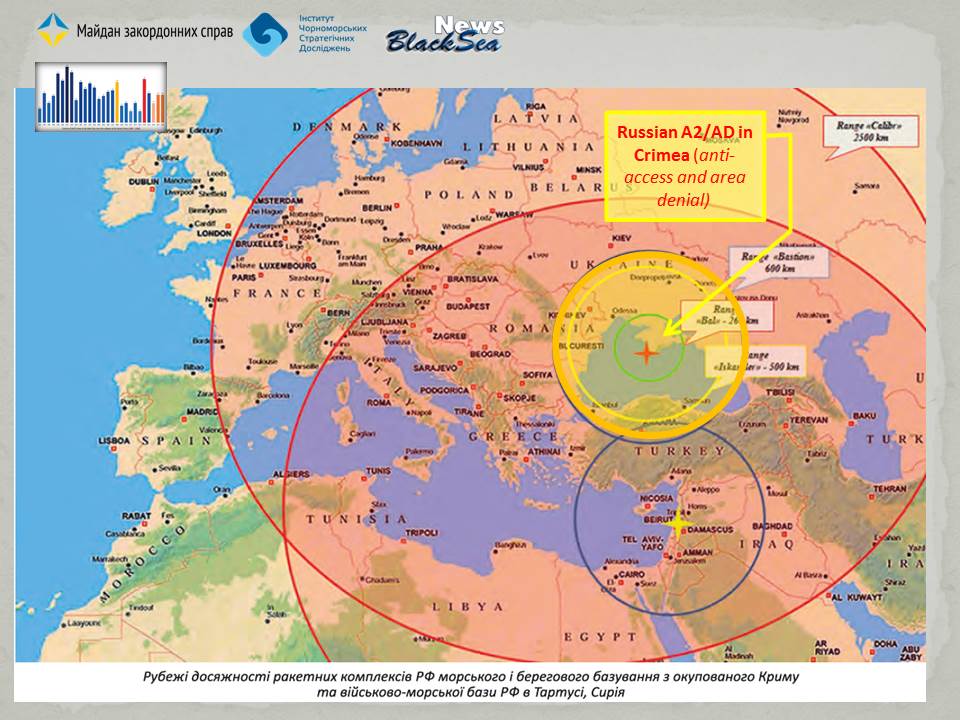

In 2020, the obstruction of the freedom of navigation in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea on the part of the Russian Federation will continue the strategy of using military capabilities, which were created on the occupied peninsula, outside Crimea.

This can be briefly described as the projection of a military threat and imperial expansion not only into Ukraine but also into the whole southeast Europe, the South Caucasus, Turkey, the «Syrian knot» in the Middle East with development in North Africa.

The point of this projection of force is to create chaos managed from Moscow wherever possible, not only in Ukraine, Moldova, and the Caucasus but also in the EU and NATO countries, and particularly in the Balkans and the Mediterranean. We can observe the effects and manifestations of these processes more and more frequently.

It is in this context that we considered in the first article the problem of the freedom of navigation in the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait, which «unexpectedly» arose in April-May 2018.

In 2020, the Russian Federation will continue to test the limits of tolerance and patience of the civilized world and its willingness to respond to Russia’s latest whims.

Based on this experience, it is possible to construct scenarios and make forecasts for 2020 regarding possible actions of the Russian Federation in the field of safety of navigation in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, and the reaction of Ukraine and the civilized world.

We predict that in 2020 the obstruction (under various pretexts) of vessel traffic in the Kerch Strait is going to continue and will be used by the Russian Federation to keep military transportation to Crimea secret.

However, our main forecast concerns not the Sea of Azov, with which almost everything is clear, but the situation with the freedom of navigation in the Black Sea.

We are almost certain that the Azov crisis was an «exercise». In 2020, further actions of the Russian Federation aimed at obstructing the navigation to Ukrainian ports should be anticipated not only in the Sea of Azov but also in the Black Sea.

The Sea of Azov export from the Ukrainian ports is only a small part in comparison with the export from the numerous Odesa, Mykolaiv, and Kherson ports. The main export-import routes of Ukraine are in the Black Sea and lead to/from the Bosphorus.

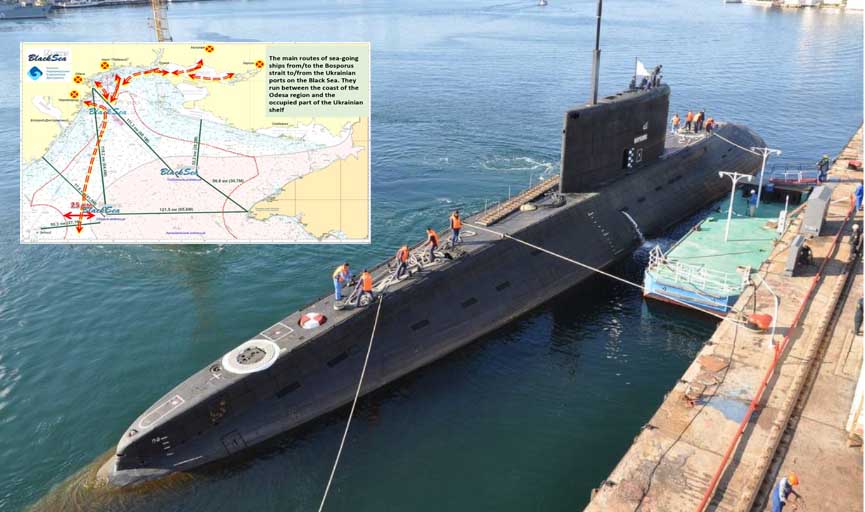

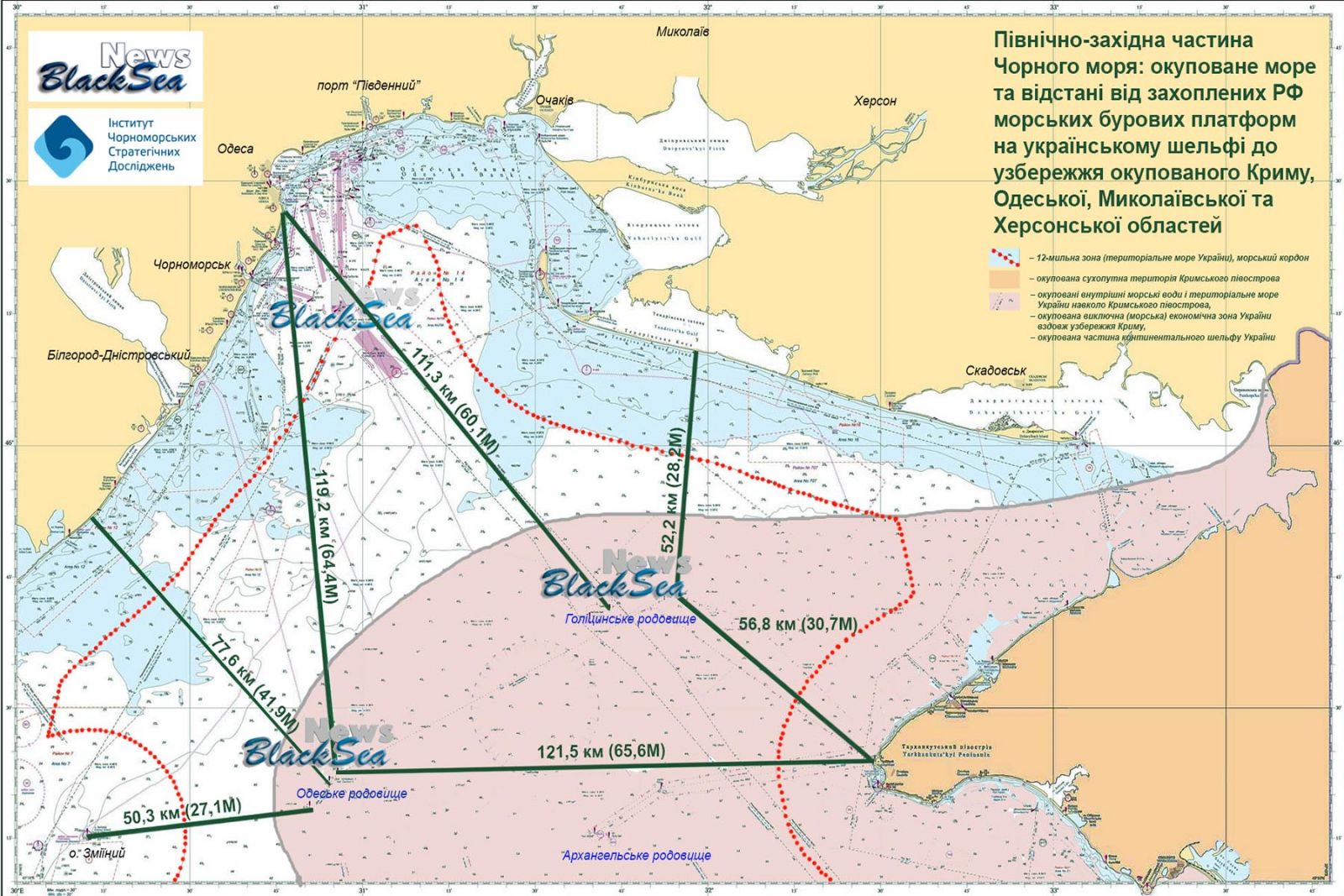

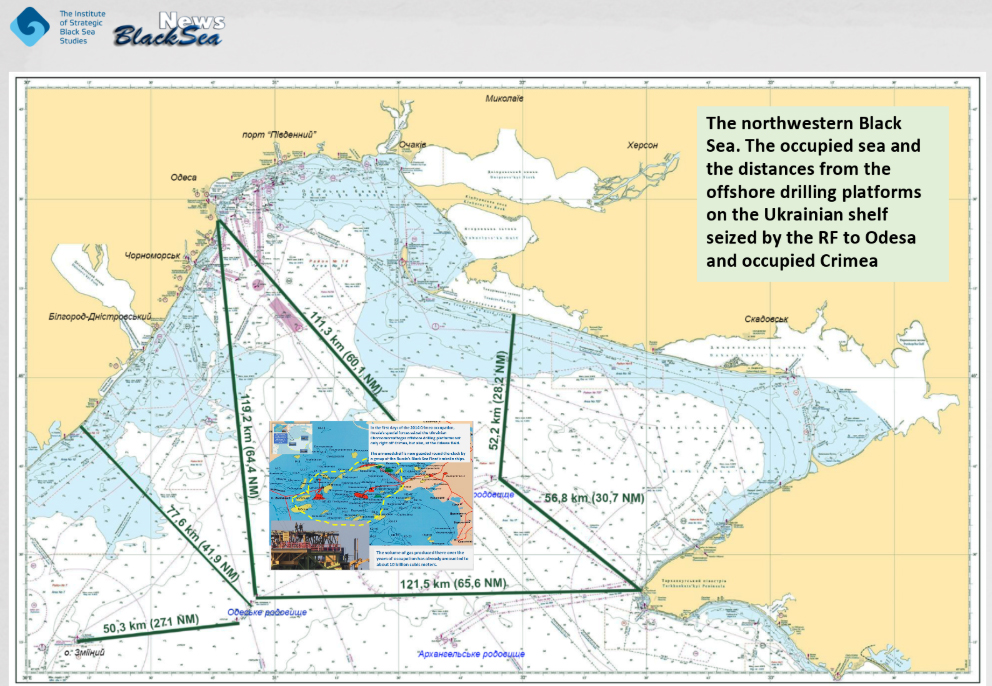

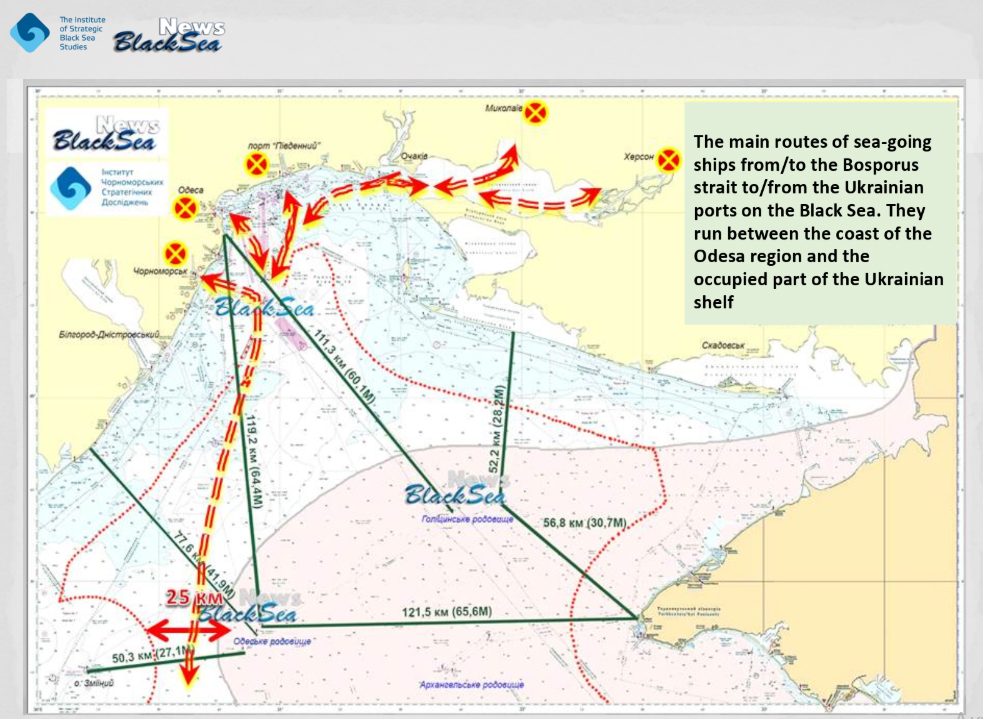

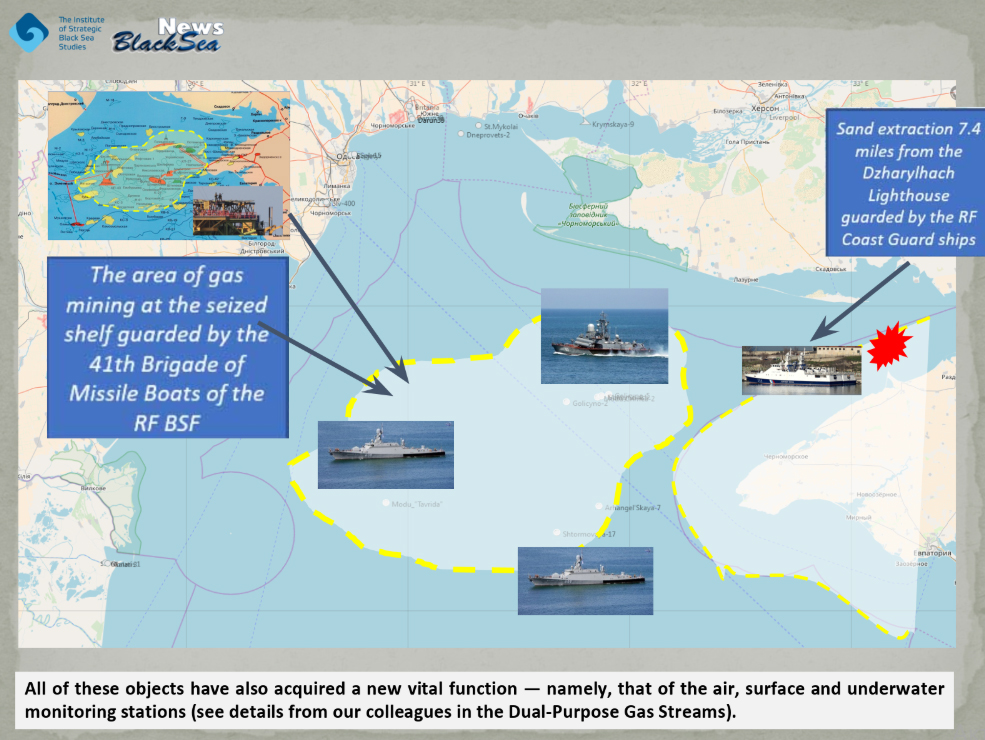

In the Black Sea – near the recommended sea routes from Odesa to the Bosphorus and from Odesa to Batumi and the Turkish Black Sea ports – the Ukrainian offshore oil platforms are situated, which were captured by Russia during the occupation of Crimea (see the map).

Few people pay attention to the fact that the Odesa offshore field – the notorious «Boyko's drilling rigs» – is closer to the coast of Odesa than to occupied Crimea.

The distance from the nearest drilling rig seized by Russia to the coast of the Odesa region is 77.6 km (41.9 miles), to Zmiinyi Island – 50.3 km (27.1 miles), and to Cape Tarkhankut in occupied Crimea – 121.5 km (65.6 miles).

From the coast of the Kherson region, the distance to the nearest seized drilling rig is 52.2 km (28.2 miles).

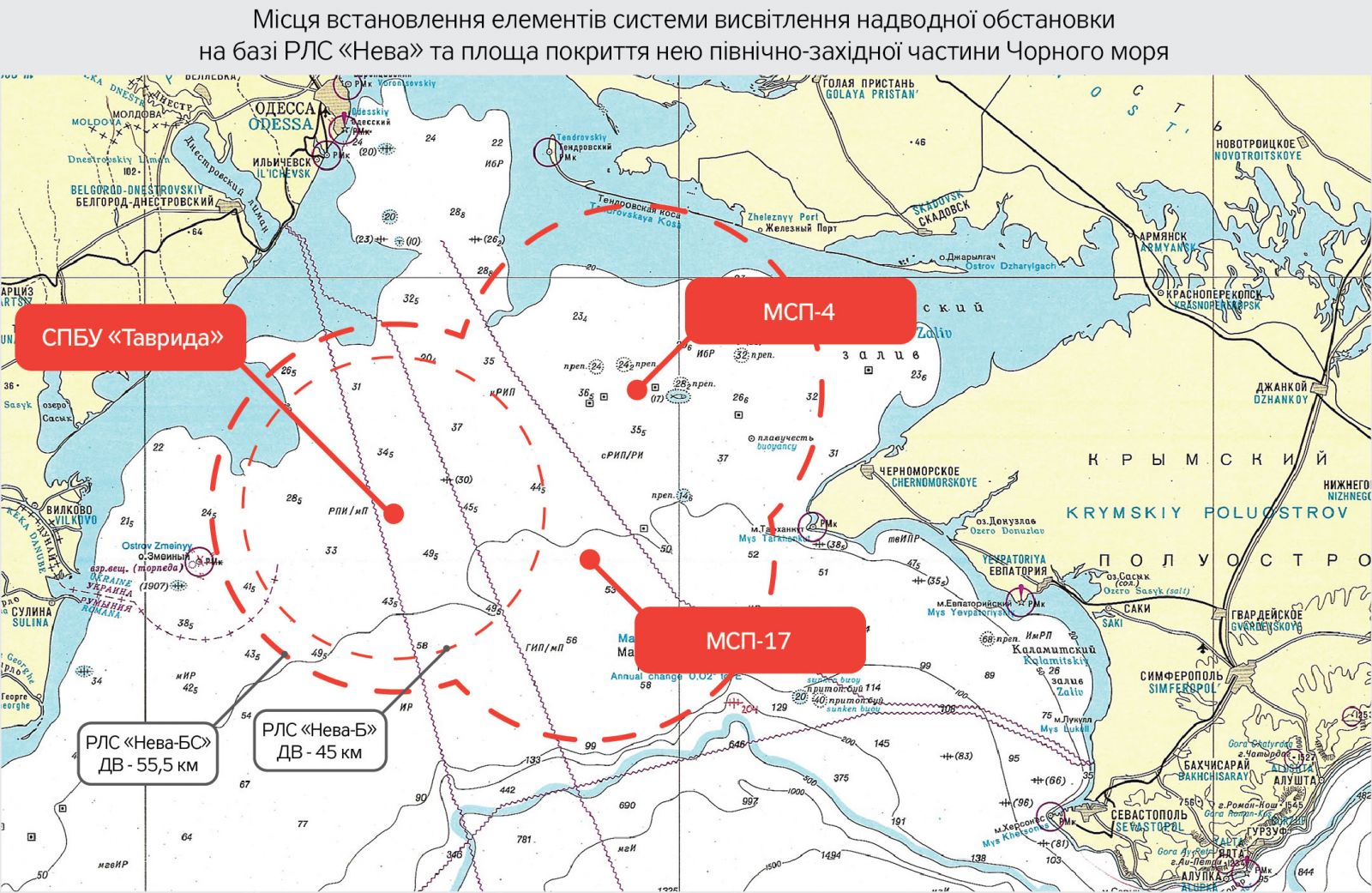

On every sea platform and every drilling rig, a garrison of Russian special forces or marines has long been deployed, as well as underwater, sea-surface, and air situation surveillance radars. There are about ten such military objects on the Ukrainian shelf (see the details in our colleagues’ material Dual-Purpose Gas Streams).

On every sea platform and every drilling rig, a garrison of Russian special forces or marines has long been deployed, as well as underwater, sea-surface, and air situation surveillance radars. There are about ten such military objects on the Ukrainian shelf (see the details in our colleagues’ material Dual-Purpose Gas Streams).

While in the past the areas of the Odesa, Holitsynske, Arkhangelske, and Shtormove offshore fields were patrolled by auxiliary ships of the Russian Federation, since 1 June 2018, the guarding of the captured Ukrainian drilling rigs on the occupied shelf has been officially taken over by the 41st brigade of small-size missile ships of the Black Sea Fleet of the RF.

While in the past the areas of the Odesa, Holitsynske, Arkhangelske, and Shtormove offshore fields were patrolled by auxiliary ships of the Russian Federation, since 1 June 2018, the guarding of the captured Ukrainian drilling rigs on the occupied shelf has been officially taken over by the 41st brigade of small-size missile ships of the Black Sea Fleet of the RF.

There is constant rotation, and these are the warships with significant potential.

Therefore, it is logical to imagine the scenario where the RF starts to delay for inspection vessels en route to or from the ports of Chornomorsk, Odesa, Mykolayiv, and Kherson, applying the so-called «Azov technique».

The FSB can easily report that one of the ships plying this route may have a sabotage group aboard that wants to blow up, for example, drilling platforms on the stolen Odesa offshore field (which Russia already considers its own, as well as the whole Ukrainian shelf, where it produces/steals up to 2 billion cubic meters of gas annually).

If they do that once, twice, or three times, we can only imagine what will happen to maritime traffic in the area. This may not happen if appropriate preventive measures are taken, but such a scenario should be «on the table».

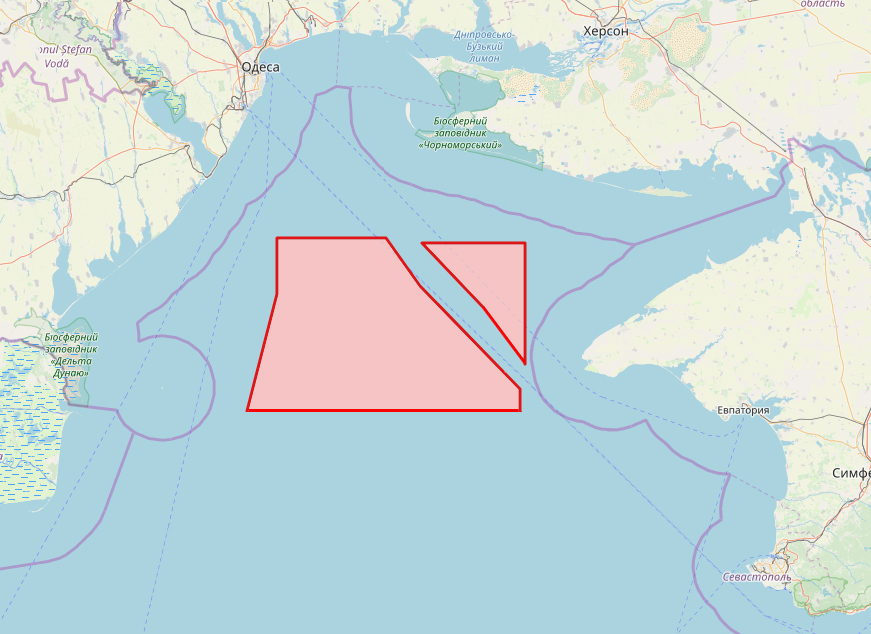

Note that the recommended routes of vessels from the Bosphorus to Ukrainian ports go through the narrow gap between Zmiinyi Island and the Ukrainian shelf in the Odesa offshore field occupied by the RF. It's a neck that is only 13.5 miles (25 km) wide – see the map.

Another our forecast, which is also based on the monitoring and analysis of the trends in Russia's «Black Sea experiments» in 2019, is as follows:

In 2020, one of the Russian methods for obstructing navigation in the Black Sea will be the expansion of the practice of closing the western areas of the sea for navigation under the pretext of conducting live-fire exercises, whether real or make-believe….

It is worth reminding that on 1-12 July 2019, during the Ukrainian-American naval exercise Sea Breeze 2019, one of the planned exercise areas in the region of the Black Sea from Ukrainian Zmiinyi Island near the Odesa coast to the Cape Tarkhankut in Crimea, that is, in the area where the occupied shelf with gas fields is situated, was closed.

This was done through the issuance of the international warning of navigational danger by the RF.

This was done through the issuance of the international warning of navigational danger by the RF.

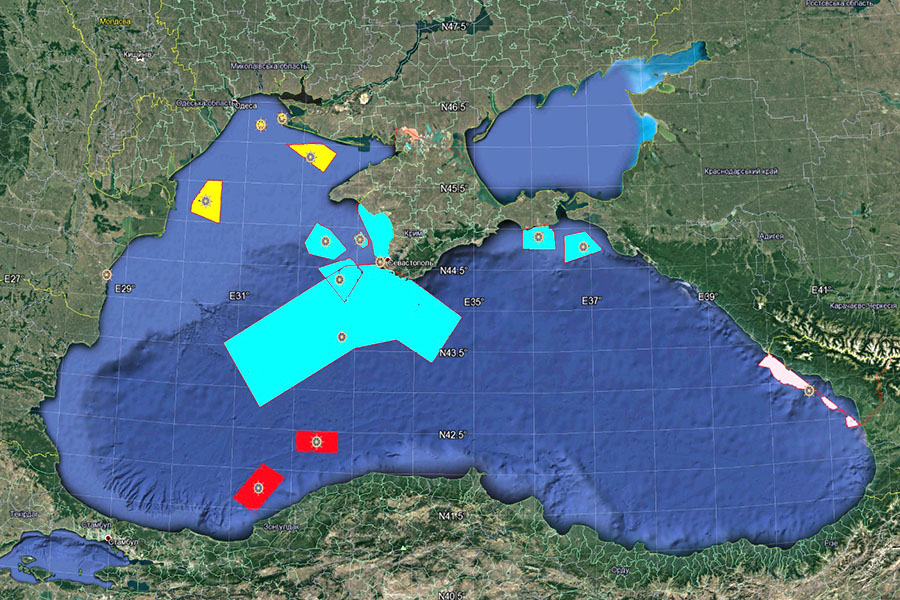

And since 24 July 2019, the RF has already closed five areas in the Black Sea, including in the maritime exclusive economic zone of Bulgaria and Romania, and almost entirely the eastern Black Sea from Sochi to Turkey to hamper the Georgian-American exercise Agile Spirit 2019.

The combined area of the Black Sea regions blocked by the Russian Navy in July 2019 alone far exceeded 120,000 square kilometres, or more than ¼ of the total Black Sea area. The goal of these actions is to form a «habitual» perception that the entire Black Sea is Russia’s zone of influence. This is Russia's strategy for driving NATO out of the Black Sea.

The combined area of the Black Sea regions blocked by the Russian Navy in July 2019 alone far exceeded 120,000 square kilometres, or more than ¼ of the total Black Sea area. The goal of these actions is to form a «habitual» perception that the entire Black Sea is Russia’s zone of influence. This is Russia's strategy for driving NATO out of the Black Sea.

Since the first days of 2020, we have already observed a similar pattern – even with some development.

On 2 January 2020, closure of certain Black Sea areas as a result of issuing NAVTEX international maritime hazard warnings about conducting live-fire exercises was as follows:

Closure of areas: in yellow – the Ukrainian Navy, in pink – the Georgian Coast Guard, in red – the Turkish Navy, in turquoise– the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Closure of areas: in yellow – the Ukrainian Navy, in pink – the Georgian Coast Guard, in red – the Turkish Navy, in turquoise– the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

In the largest of these areas, south and southwest of the occupied Crimean Peninsula, on 9 January 2020, the unprecedentedly large-scale joint missile-firing exercise of the Black Sea and Northern Fleets was conducted with missile launches from the sea, air, and shore.

This exercise deserves special attention.

For the first time since Soviet times (!), we saw such a huge naval group of the Russian Federation at the Black Sea exercise – about 40 ships, a submarine, and over 40 planes and helicopters of different types participated in the exercise:

from the Black Sea Fleet: the new missile frigates Admiral Grigorovich, Admiral Makarov (carriers of Kalibr cruise missiles), the small-size missile ships Orekhovo-Zuevo, Ingushetia, Vyshny Volochek (carriers of Kalibr cruise missiles), the missile boats Naberezhnye Chelny, Ivanovets, Shuya, R-60, the large landing ships Caesar Kunikov, Orsk, Saratov, Novocherkassk, and Azov, the new patrol ships Dmitry Rogachev and Vasily Bykov, the new submarine Kolpino (a carrier of Kalibr cruise missiles), the guided missile air cushion ship Samum, the small antisubmarine ships Kasimov, Muromets, the minesweeper Ivan Antonov, the anti-sabotage boats P-355, Yunarmeets Kryma, P-834, P-835, P-838, P-845, the landing boat D-296, the tanker Ivan Bubnov, the repair ship PM-56, the rescue tugs Sergey Balk, Captain Guryev, SB-739, Epron, PZhS-123.

From the Northern Fleet: the guided missile cruiser Marshal Ustinov (President Putin, the Defence Minister Shoigu, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Navy Yevmenov were aboard this ship, where the headquarters was established), and the large anti-submarine ship Vice-Admiral Kulakov;

the air force: Su-30SM multirole fighters, Su-24M front-line bombers, and Tu-95 strategic heavy bombers and missile carriers, naval helicopters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, unmanned aerial vehicles; the participation in the exercise of the Il-38 anti-submarine warfare aircraft of the Northern Fleet deserves special attention.

During the exercise, a pair of MiG-31k fighters fired a Kinzhal aeroballistic (hypersonic) missile at a target on one of the ranges.

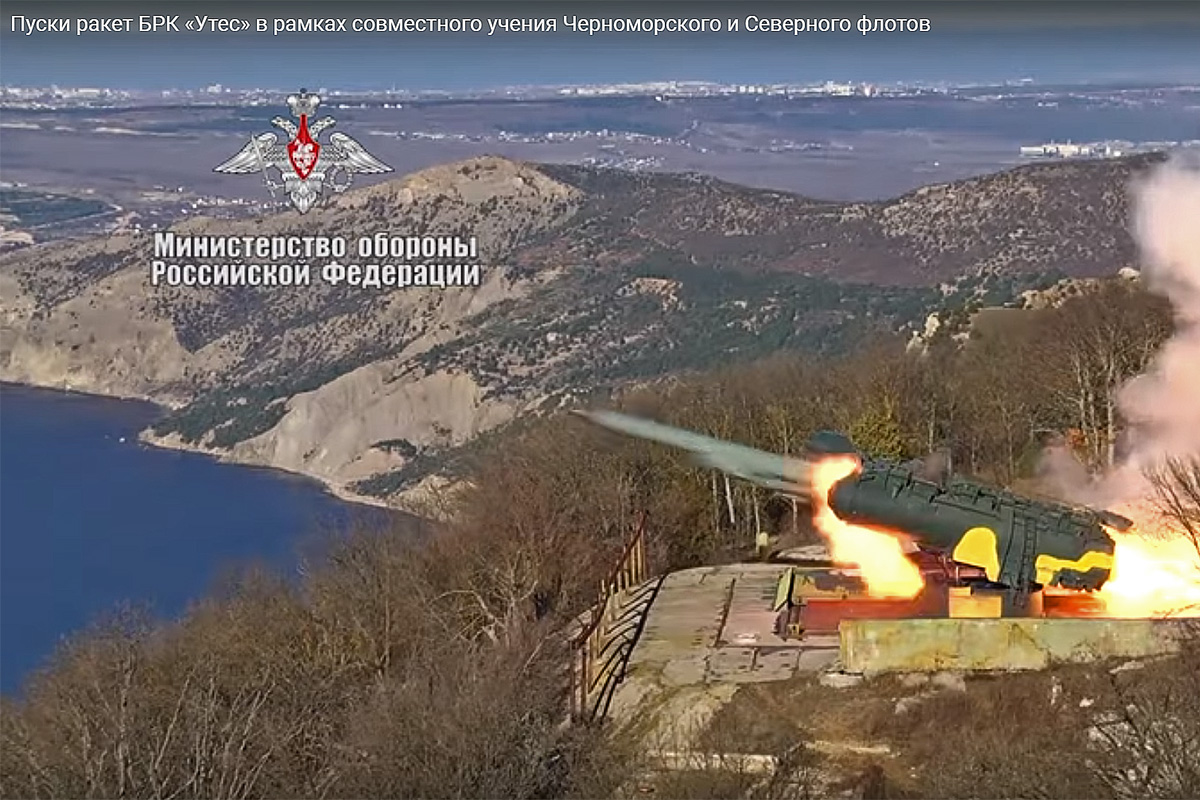

The Admiral Grigorovich frigate, the small-size missile ship Orekhovo-Zuevo, and the submarine Kolpino launched Kalibr cruise missiles from surface ships and submarines; the missile boats Ivanovets and Naberezhnye Chelny launched Moskit anti-ship missiles. The Utes silo-based coastal missile system (*) carried out two missile launches at targets that simulated enemy ships.

(*) In November 2016, the Utes silo-based coastal missile system produced in Soviet times was put back in operation after being restored by the Black Sea Fleet of the RF. It is located in the area of Cape Aya (Balaklava district of the city of Sevastopol). Since 2016, it has been regularly firing Progress anti-ship missiles (a modernised version of the Soviet P-35 anti-ship missile). Its range is up to 460 km. It is equipped with a 560-kilogram high-explosive warhead or a nuclear warhead of up to 20 kilotons. In the coming years, the Utes system will be replaced by the first Bastion-S silo-based coastal defence missile system (up to 36 Onyx missiles).

(*) In November 2016, the Utes silo-based coastal missile system produced in Soviet times was put back in operation after being restored by the Black Sea Fleet of the RF. It is located in the area of Cape Aya (Balaklava district of the city of Sevastopol). Since 2016, it has been regularly firing Progress anti-ship missiles (a modernised version of the Soviet P-35 anti-ship missile). Its range is up to 460 km. It is equipped with a 560-kilogram high-explosive warhead or a nuclear warhead of up to 20 kilotons. In the coming years, the Utes system will be replaced by the first Bastion-S silo-based coastal defence missile system (up to 36 Onyx missiles).

It is worth reminding that in 2019 simulation air attacks of the Russian military aviation on NATO ships during their stay in the Black Sea, as well as simulation attacks on the Ukrainian Black Sea ports, became familiar (on 10 July 2019, a Russian Tu-22M3 missile carrier simulated a missile strike against Odesa from the distance of 60 km).

As to amphibious assault training, it is regularly conducted by the Black Sea Fleet of the RF at the range of Opuk in occupied Crimea.

In September 2020, the Southern Military District of the RF (and it appears that not only it) will participate in full force in the large-scale Caucasus-2020 strategic command post exercise (SCPX).

About 100 warships and auxiliary vessels will take part in it. And it can be predicted that not only the ships of the Black Sea Fleet and the Caspian Flotilla will participate.

The main purpose of such exercises is to train for a large joint military operation in the south and south-western theatres of war.

Undoubtedly, the joint exercise of the Black Sea and Northern Fleets suggests another peculiarity of 2020 – the collective training of different fleets staffs and joint force groupings has already begun. This practice is being actively implemented in the Russian army based on the Syrian experience.

The berths of the 30th Surface Ship Division. The beginning of January 2019.

The forecast does not exclude the possibility of the RF’s active operations on the Ukrainian coast of the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov, and the Danube, including an amphibious assault. The period after the celebration of the 75th anniversary of the victory over fascism should be considered particularly dangerous…

In the south – at sea, on land, and in the air – the Russian advantage is absolute, and the RF cannot but plan appropriate options if «the circumstances arise». Especially under the conditions where the strategy of building gas pipelines bypassing Ukraine sooner or later inevitably reduces such a deterrent against a hot war as the transit of Russian gas to Europe through Ukrainian pipes.

* * *

Until the Ukrainian Navy is substantially strengthened, the Ukrainian authorities will have to make proposals to the USA and NATO again to continue and extend the patrols of the permanent groups of the NATO Allied Maritime Command and the U.S. Sixth Fleet in the Black Sea.

It is worth reminding that from March 2014 almost 90% of the days until the end of the year, the ships of the NATO non-Black Sea countries regularly patrolled the Black Sea. In our opinion, thanks to this fact, among other things, the «Odesa People's Republic» was not created in Ukraine.

Later on, NATO's naval presence in the Black Sea varied depending on different circumstances (this will be discussed separately), but overall, in 2014-2019 NATO not only recognised the Black Sea threat but also found the resources to increase its presence in the region quite significantly in 2019.

However, NATO's naval presence in the Black Sea will certainly depend on the situation in the neighbouring regions of the world – Syria, Iraq, Iran, North Africa...

If developments in the Black Sea follow the scenario outlined above, we may need to apply the experience that has worked in the Sea of Azov since October 2018 to major Black Sea routes.

The Azov experience has shown that open sea detentions of merchant vessels on the move stopped when the Ukrainian Navy started to escort commercial vessels from Mariupol to Kerch.

In 2020, Ukraine may have to resort to military escorts for commercial shipping or to patrolling international maritime routes in the Black Sea and inviting NATO countries ships to do so.

The best option for this would be to establish a special naval format of «the operation to maintain the freedom of navigation» in the Black Sea.

Of course, in 2020, Ukraine will continue to strengthen its maritime capabilities.

It is likely that against a backdrop of real threats to the freedom of navigation in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, which were finally acknowledged in 2018-2019, both in Ukraine and abroad, a maritime policy may finally be developed in Ukraine.

So far, Ukraine is still a state with land thinking, where people are used to moving and fighting on oxen, horses, tachankas (horse-drawn machine gun carriers), armoured personnel carriers, and tanks.

An encouraging factor that seems to have been ignored by Russian strategists is that freedom of navigation is one of the fundamental principles of the civilized world. Along with freedom of trade and human rights. Therefore, the involvement of the world community in countering these threats inspires hope for some positive results in 2020.

* * *

This publication has been produced with the support of the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Its contents do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of EED. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this publication lies entirely with the authors.

This publication has been produced with the support of the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Its contents do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of EED. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this publication lies entirely with the authors.

More on the topic

- 11.12.2018 Russia's Economic War Against Ukraine in the Sea of Azov as of December 1, 2018: The Technology of Blocking the Mariupol and Berdyansk Ports

- 13.07.2018 Illegal Visits of Foreign Citizens to the Territory of the Occupied Crimea in Ferbruary-May 2018 — the Monitoring Results

- 04.06.2018 Database of the Russian Airlines that Flew to the Occupied Crimea in May 2018

- 03.03.2018 Illegal Visits of Foreign Citizens to the Territory of the Occupied Crimea in December 2017-January 2018 — the Monitoring Results

- 27.02.2018 The Illegal Mining of Natural Resources in Crimea. Part 2. The Development of the Stolen Sea

- 23.02.2018 The Illegal Mining of Natural Resources in Crimea. Part 1. The Development of the Stolen Shelf

- 13.01.2018 Ilmenite Cargo Reloaded in the Kerch Strait onto the German Ship Again

- 27.12.2017 German Ship Delivers 10,000 Tons of Ilmenite from Norway to the Occupied Crimea’s Titan Plant – a BSNews Investigation

- 26.12.2017 Illegal Visits of Foreign Citizens to the Territory of the Occupied Crimea in October 2017 – Monitoring Results

- 19.12.2017 November 2017 Violations of the Crimea Maritime Sanctions: Grain Export and Cement and Ilmenite Import

- 15.12.2017 The Illegal Visits of Foreign Citizens to the Occupied Crimea in September 2017 - the Monitoring Results.

- 14.12.2017 Violation of the Crimean Maritime Sanction in September-October 2017: the Lebanese-Egyptian Fleet