A fleet of drones and the new naval warfare

Artem GALUSHKO,

a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Law of the Arctic University of Norway (UiT)

For a county with a rather modest fleet of warships (Axe, 2022) Ukraine has fared unexpectedly well up to now against the powerful amphibious forces of the Russian Federation in the ongoing Black Sea warfare. The destruction of the Russian Alligator-class landing ship Saratov in the Ukrainian port of Berdyansk on 24 March 2022 (Sutton, 2022), the recapture of the strategically important Snake Island, now a symbol of Ukrainian resistance, on 7 July 2022 (Bushard, 2022) and finally the sinking of the Slava-class cruiser Moskva, a flagship of the Russian Black Sea fleet, on 14 April 2022 (Ackerman, 2022) could be a sign of a different format of future naval warfare, where the might is not always right. My blog describes the subsequent naval warfare developments and provides arguments in favor of this new age warfare environment.

The following events have unfolded in the naval standoff between Russia and Ukraine.

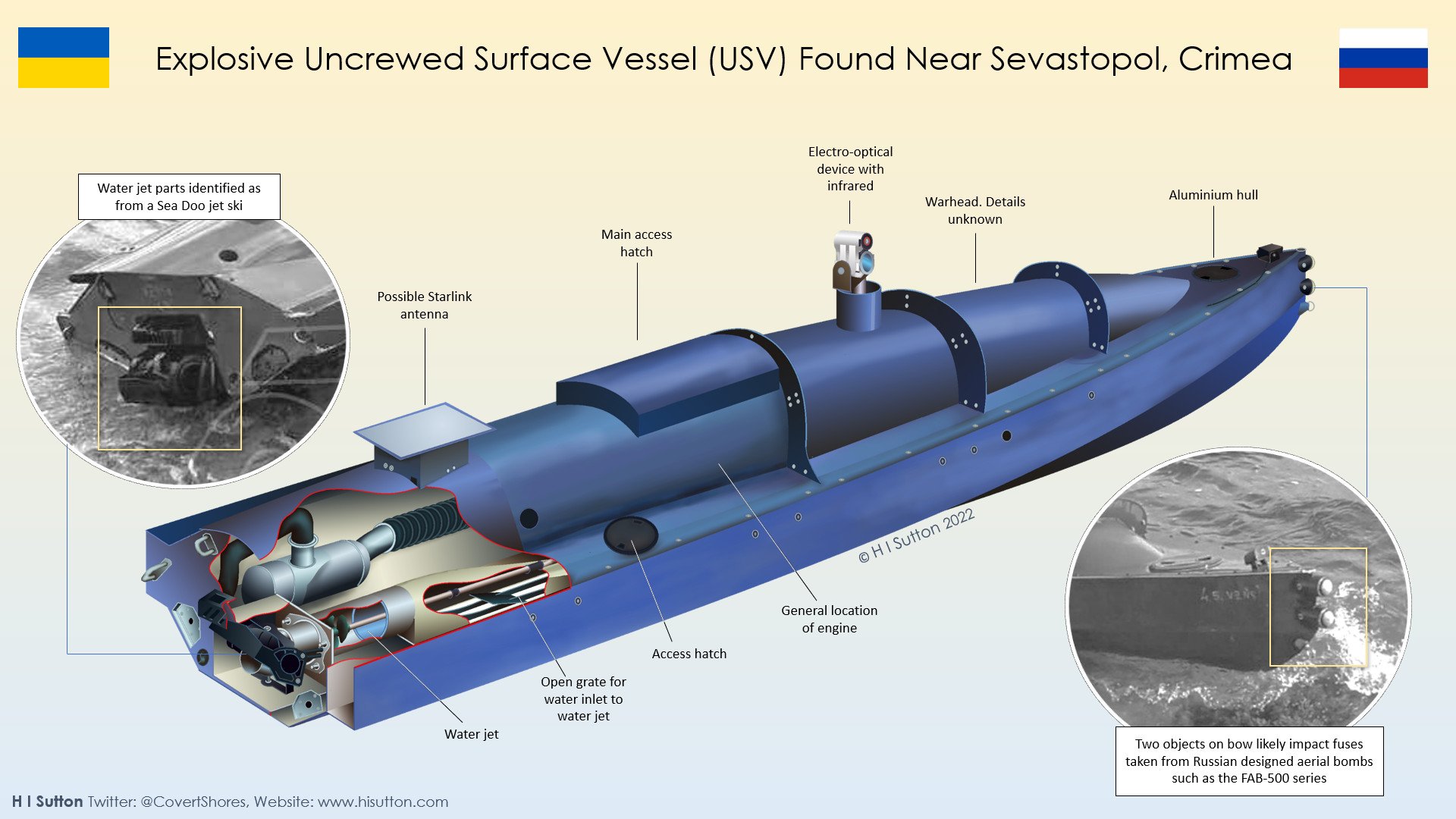

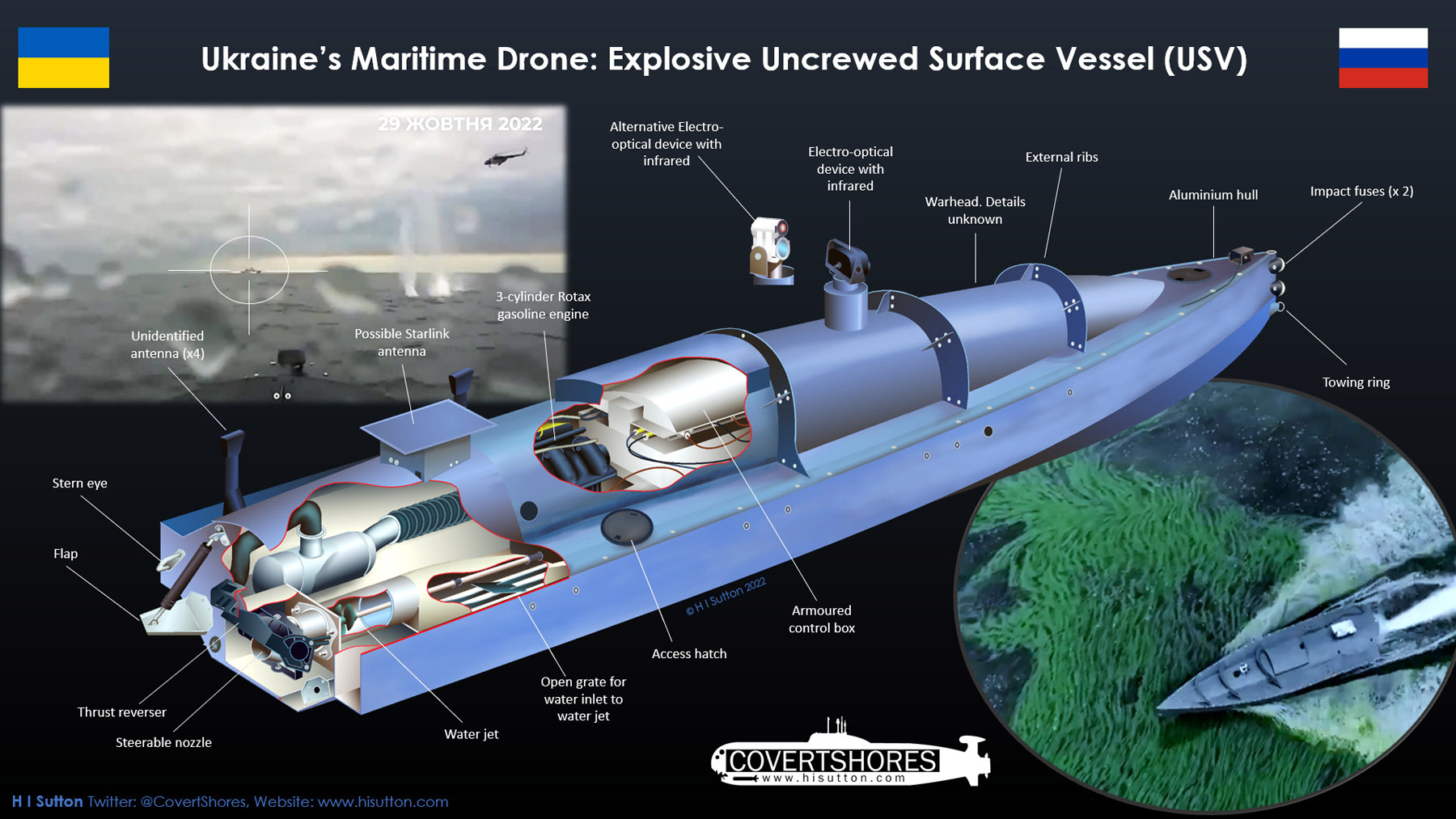

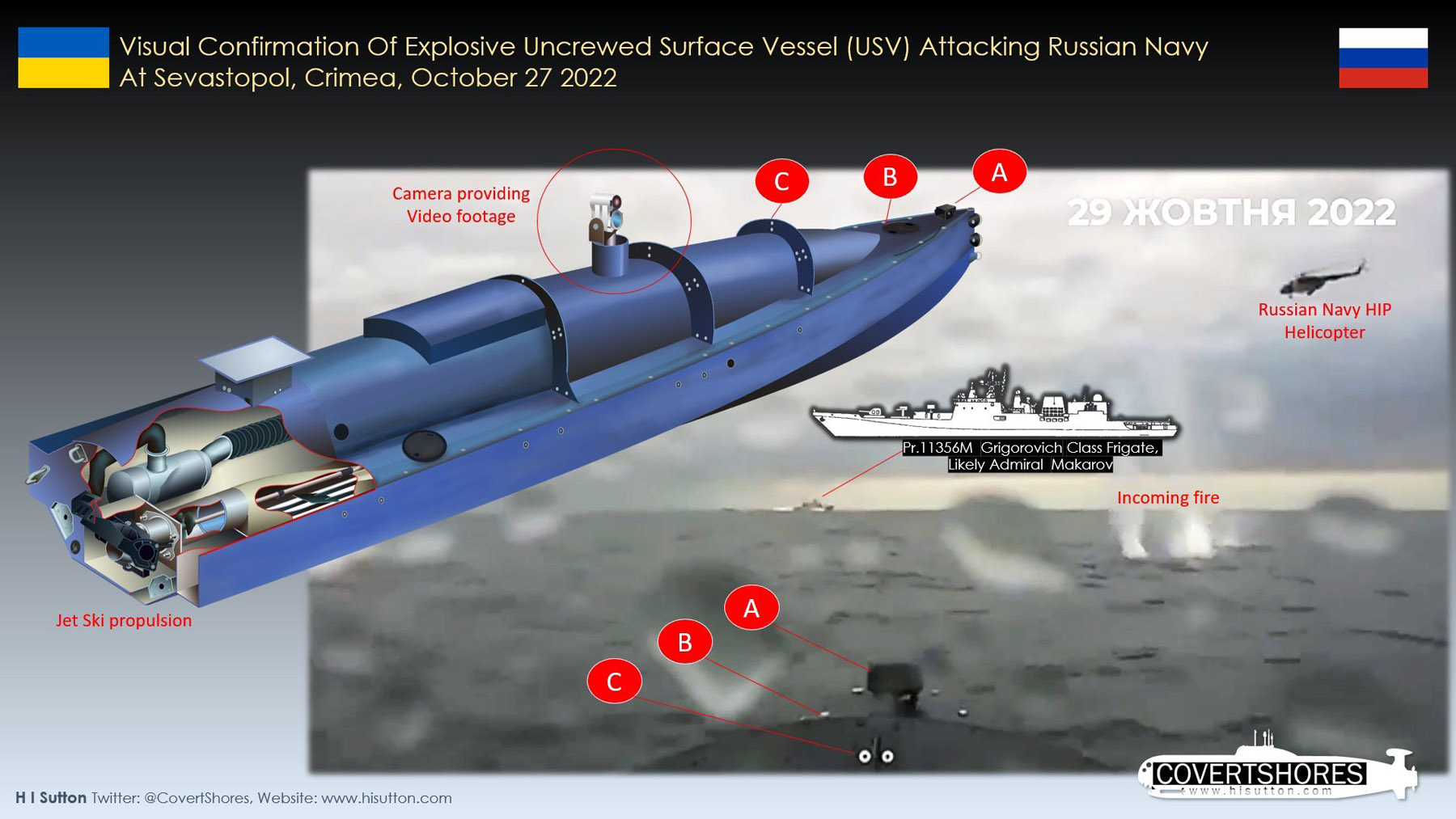

On 29 October 2022, a ‘swarm’ of seven maritime drones/unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) and nine unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have covered around 300 km distance, undetected by radar systems, safely reached the protected harbor in Sevastopol, Crimea, and attacked the Russian naval base, coordinating themselves via a satellite communication system akin to Starlink.

The attack outcomes: reported damages of a Russian military frigate and a demining ship (Bachega and Gregory, 2022). On 11 November 2022, Ukraine has announced an intention to create the world's first naval fleet of drones with the help of a crowdfunding initiative ‘United24’ (it contains footage of drones with a certain resemblance to USVs that attacked the Russian naval infrastructure near Sevastopol, Crimea). As opposed to UAVs, USVs navigate on water surface to conduct anti-submarine warfare, maritime security operations, mine countermeasures and other types of maritime surface tasks (see the USV Master Plan).

The initial goal is to assemble a ‘mosquito fleet’ of 100 medium and small USVs, whose tasks will include:

a) protecting ports and territorial sea,

b) patrolling the coastal area,

c) preventing enemy warships from leaving their military bases,

d) defending merchant vessels from possible attacks,

e) accompanying naval operations;

f) other military missions, surveillance and reconnaissance.

Between 16 and 18 November 2022, the second ‘drone attack’ against the Russian naval base and oil terminal ‘Sheskharis’ took place in Novorossiysk, Russia. Though Russian authorities and media provided conflicting reports and eventually denied the attack, these latest examples of modern naval warfare have attracted significant attention of various expert communities.

Novelty of USVs weaponization and its significance for modern naval warfare

While the Government of Ukraine has still not acknowledged its involvement in the drone raids on Sevastopol and Novorossiysk, in military terms, Ukraine gains strategically from the outcomes of these attacks. Unlike Russia, which targets the essential civilian infrastructure and civilians in Ukraine deliberately violating international humanitarian law, the allegedly Ukrainian drone attacks undermine the Russian oil industry as a motor of Kremlin’s war machine and the Russian naval infrastructure, whose submarines and warships launch cruise missiles against non-military targets like kindergartens, children’s playgrounds and maternity hospitals (Fawler, 2022). Though the war has motivated the Ukrainian Navy to be more resourceful, the actual effectiveness of maritime drones (USVs) employed in the Russia-Ukraine naval hostilities appears to be a result of a larger trend in modern warfare rather than a sporadic moment of tactical success.

Naval drones already perform various functions and assist with operations of major navies. In Canada the National Defense and the Royal Canadian Navy use a solar-powered ocean drone Data Xplorer to protect whales and other marine mammals during military operations (Moloney, 2022). In the US large marine drones like Sea Hawk and Sea Hunter help the Navy and Coast Guard to track submarines and conduct other routine operations (LaGrone, 2021). While the British Royal Navy will spend 2 million pounds to purchase additional autonomous underwater vehicles REMUS 100M (Remote Environmental Monitoring Units) (Grinter, 2022), Türkiye has launched the production of its own anti-submarine unmanned surface vessels called ULAQ (Bekdil, 2021). Multi-purpose autonomous surface vessels for polar marine research (MASP) provide effective assistance in the collection of marine geological, oceanographic, and glaciological data from the coastal areas in the Arctic (Camus et al., 2021). China, Israel and Iran are also reportedly working to create their own fleets of naval drones.

Explosive-laden maritime drones in the Ukraine-Russia conflict:

There is a considerable novelty of the Ukrainian approach to maritime drones. While other countries have started using naval drones for miliary purposes, so far only Ukraine has explored the application of explosive-charged unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) during the ongoing international military conflict. These USVs with pre-installed warheads essentially function as kamikadze drones or loitering munition which can wait (loiter) until the target is identified and confirmed, while a remote operator still has an opportunity to abort the attack.

Furthermore, unlike other naval surface vehicles that are stationed on ships, Ukrainian USVs presented on the ‘United24’ crowdsourcing platform act as semi-autonomous weapon systems that do not have to be launched from a ‘host/mother ship’.

The ‘Swarm tactic’ employed by maritime and aerial drones during the attack against the naval base in Sevastopol marks a new development in naval warfare. Although states have already deployed unmanned surface vehicles during military hostilities (LaGrone, 2017), the Sevastopol and Novorossiysk incidents are the first documented cases of using a swarm of naval drones to attack military targets and critical infrastructure. The effectiveness of the naval drones, demonstrated in both attacks, had a profound impact on the Russian navy and its operations. Russian warships stationed in the two naval bases have significantly reduced their activities, while Russian tankers stopped transportation of oil from one of the biggest oil terminals in Novorossiysk.

Ukraine can share its cost-effective approach and technological know-hows with other countries in terms of development and actual deployment of unmanned vehicles (both UAVs and USVs) in combat missions.

In financial terms, the ‘United24’ fundraiser has demonstrated that the actual cost of producing the entire fleet of maritime drones is far less than producing just one modern warship. Moreover, the attacks against the Russian navy have confirmed that small, maneuverable and inexpensive drones could cause far more significant damages to expensive naval infrastructure of the belligerent party. While the consequences and outcomes of the naval drone attacks in Sevastopol and Novorossiysk will probably be studied and taught in military academies, major navies will have to review their tactics and procedures to counteract similar drone attacks (Kallenborn, 2023) that may become a part of conventional naval warfare in the future.

Possible legal issues, applicable law and two regulatory regimes

All these recent developments may provide a glimpse at the future of armed conflicts and the modern warfare environment predominantly based not only on new technologies, but also on human factor.

Unlike the conventional combat strategies built around the military might (i.e., a total number of military platforms such as warships, fighter jets and tanks), the key element of the new warfare is its reliance on an individual equipped with ‘smart’ but inexpensive weapons capable of destroying big-budget military equipment. An example of this new warfare would be a person or a group of people who can destroy a warship, whose production took millions of investors’ money over many years, by using explosive-laden naval drones mass-produced within months with minimum expenses. There is thus a greater danger that state and non-state actors can potentially misuse these novel technologies to avoid responsibility in the so-called ‘hybrid warfare’ activities.

Nevertheless, such modern naval warfare does not render International Law irrelevant. On the contrary, the distinction between applicable legal regimes and possible classifications become even more crucial for the sake of clarity and predictability of law and warfare. Here it is necessary to differentiate between 2 distinct regimes applicable to naval drones used either in times of peace or during an ongoing armed conflict. The latter is clearly the case of Sevastopol and Novorossiysk drone attacks conducted in the framework of military hostilities between Russia and Ukraine “plainly engaged in an international armed conflict’ (Layne, 2023, see also the ICC report on preliminary examination activities, 2016). In this war context, the norms of peacetime maritime activities and, in particular, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) will not be directly applicable to the naval drone operations in the Black Sea addressed in this blog.

The Regime of Peacetime Operations

Even though the legal regime governing the use of naval drones in peacetime is not applicable to the current military conflict between Ukraine and Russia, it is useful to outline its general norms that can be potentially applicable to USVs as a class of equipment. In this regard, the legal status of USVs plays a crucial role. The legal qualification of an USV as a craft or a vessel will, in turn, determine rights and obligations applicable to this modern equipment. If an USV is qualified as a ship or a vessel, it may have navigational rights and enjoy the innocent passage regime as long as neutral coastal states do not prohibit such passage in their territorial sea On the one hand, there is a great variety of approaches to the definition of a vessel in international law (Tuckett, 2023). On the other hand, this variety gives an opportunity to use different methodologies and treaties to determine the status of USVs in various contexts and legal frameworks (i.e., COLGREG, OILPOL, MARPOL and others). However, due to the general lack of clarity towards novel technologies in often outdated applicable norms of international law, the expert community is mostly in agreement (Schmitt and Goddard, 2017) that the matter of legal status of unmanned surface vehicles is rather contentious and “remains unresolved”.

Another aspect of the legal analysis is a sea area, where maritime drones operate. The rule of thumb (AP I Article 51 (4)) in this regard is that both civilian and military drones should not be used in international straits and sea areas with high traffic of civilian vessels, where a risk of a collision or any other incident would be much higher. When USVs operate in territorial sea of foreign states (internal waters, territorial sea, and archipelagic waters), these states may grant or deny the passage rights to USVs under certain conditions and restrictions as long as they do this on a non-discriminatory basis. The deployment of such drones should also not endanger the maritime life (SOLAS) and activities of other states related to the exploitation of natural resources, shipping traffic and the operation of the undersea infrastructure like cables and pipelines (San Remo Manual). Other legal issues related to the deployment of USVs may include questions about USVs that are either in a trial mode or have continuous operations, type, and size of USVs used for scientific research or other tasks, safety of maritime navigation and liability for accidents caused by maritime drones.

The Regime of Naval Warfare applicable to the Ukraine-Russia conflict

Because of the ongoing military hostilities between Russia and Ukraine, the law of armed conflict would be the most appropriate framework for addressing the question whether naval drones can be qualified as lawful means of conducting war. Both Russia and Ukraine are parties to the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (AP I) relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts. In this regard, a possible starting point for evaluating the legality of explosive-laden maritime drones deployment in international military conflicts could be Article 36 (new weapons) of the Protocol, which requires to review new means of warfare and to check whether their deployment could potentially violate the norms of the Protocol or any other rule of international law applicable to the contracting parties. It is unknown whether Ukraine has conducted this legal review because the Government of Ukraine has not acknowledged its involvement in the drone attacks. However, even though much information about the plan and execution of the attacks is still missing, the legality of using naval drones within an armed conflict would in general depend on whether they can exercise belligerent actions against enemy targets and comply with relevant requirements on similar weapons. Though in line with international customary law, only vessels designated as warships can conduct belligerent activities such as attacking enemy military targets (San Remo Manual), this blog asserts that whether a naval drone has a status of a warship is irrelevant in the present context of the Russia-Ukraine war.

First, the naval drones allegedly used by Ukraine did not bear any ‘external nationality marks’ such as a Ukrainian flag, which would qualify them as warships under Article 29 of UNCLOS. Furthermore, the Ukrainian Navy was not supposed to classify its alleged USVs as warships to use them as legitimate means of attack against the Russian bases in Sevastopol and Novorossiysk. After all, during war navies can lawfully use a broad spectrum of weapons against an adversary and by virtue of their technical characteristics, kamikadze drones are similar to naval torpedoes, missiles and mines that are already subject to detailed international regulations (the Hague Convention VIII, San Remo Manual etc.). If the naval drones in question performed a similar role as torpedoes or mines, under international law Ukraine would have to ensure that such drones would “become harmless one hour at most after…[their deployment against a potential target].” (Article 1, the Hague Convention VIII). In this sense, naval drones can still be classified as new means of warfare compatible with AP I and other rules of international law applicable both to Russia and Ukraine.

Second, in the context of Ukraine-Russia warfare, drones did not require navigational rights (Articles 17, 38, 52 and 53) pertinent to ships to be used as lawful weapons. The Black Sea basin does not have any international straits or territorial seas of third states between Ukraine and Russia that would require such freedom of navigation. Because the Sevastopol drone attack allegedly carried out by Ukraine was in Crimea within internationally recognized territorial sea of Ukraine (see the Permanent Court of Arbitration ‘Ukraine v. the Russian Federation’), it did not require innocent passage or transit passage through territorial sea of neutral (non-belligerent) states. Therefore, under the law of armed conflict Ukraine was within its rights to use drones as legitimate means of warfare against the Russian military infrastructure in the territorial seas of both states.

An additional step to define the legality of using explosive-charged maritime drones would be the level of their autonomous decision-making. The key question in the context of the international humanitarian law is whether a modern weapon system under review can differentiate between lawful (military) targets and unlawful (civilian) objectives (the principles of distinction, proportionality and precautionary measures under AP I). In this regard, the ability to distinguish between military and non-military targets will depend on the degree of remote operator’s involvement in the decision-making process and technical capacities of the given naval drone. Even if a military drone does not have the capacity to verify an unlawful (civilian) objective and terminate its mission, an operator of the drone must have an opportunity to intervene and cancel the attack to avoid the violation of the rules of the international humanitarian law (jus in bello). Sending a naval drone, which is not capable of making such a distinction between lawful and unlawful targets, to attack a port frequently used by both military and civilian ships would be an example (Schmitt and Goddard, 2017) of such an indiscriminate and unlawful attack.

If anyone had doubts about the profound transformation of warfare by modern technologies, the recent drone attacks against Russian naval bases in Sevastopol and Novorossiysk have put the record straight with regards to the dimension and the importance of these changes. While it remains to be seen whether ‘smart weapons’ will play a decisive role in the Ukraine-Russia war, an important lesson of this conflict is that the rapidly changing warfare environment places the main emphasis not on the previous military might or any conventional weapons, but on the technological ingenuity and cross-society resilience in crisis situations.

* * *

Note: Artem Galushko is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Law of the Arctic University of Norway (UiT). In 2021, he has completed his research at the Max Planck Fellow Group funded through the Era-Net project within the European Union's Horizon research and innovation programme. His research interests span European and International Law and transitional justice. He also has keen interest and solid background in civil society and public management, as his previous professional activities and academic research focus on protection of fundamental rights and systemic deficiencies incompatible with the Rule of Law. In 2017, the Yehuda Elkana Centre for Higher Education has selected Artem as a Global Fellow to teach International Law and conduct research at the University of Yangon in Myanmar. He is also a recipient of a research fellowship of the Swedish Institute (2018-2019).

Selected publications:

Book

(1) Galushko, Artem (2021) Politically Motivated Justice: Authoritarian Legacies and their Role in Shaping Constitutional Practices in the Former Soviet Union. The Hague: Asser Press/ Springer-Verlag (Online at: https://www.asser.nl/asserpress/books/?rId=13978).

Book chapters:

(2) Galushko, Artem (2022) ‘A Union or, rather, a Dis-Union of Nations? Legacies of Soviet ‘nationality policies’ and their influence on law and practice in the post-Soviet states.’ In: Leontiev L. and Amarasinghe P. (eds.) State-Building, Rule of Law, Good Governance and Human Rights in Post-Soviet Space. Thirty Years Looking Back, Taylor & Francis/ Routledge Studies in Human Rights Book Series (Forthcoming, online at: https://www.routledge.com/State-Building-Rule-of-Law-Good-Governance-and-Human-Rights-in-Post-Soviet/Leontiev-Amarasinghe/p/book/9781032055381).

Peer-reviewed journal articles:

(3) Galushko A.: (2019) „Politische Justiz in Russland. Strafprozesse gegen ukrainische Staatsbürger.“ Zeitschrift Osteuropa, Berlin, 69. Jg., 3–4/2019, S. 29–47 (Online at: https://www.zeitschrift-osteuropa.de/hefte/2019/3-4/).

(4) Antonov O., Galushko A. (2018) “The ‘Common Space of Neo-Authoritarianism’ in Post-Soviet Eurasia.” Baltic Worlds. (Online at: http://balticworlds.com/the-common-space-of-neo-authoritarianism-in-post-soviet-eurasia/).

(5) Galushko A. “The Soviet Kingdom of Crooked Mirrors and its Legacy of ‘Twofold Constitutionalism’: Politically Motivated Trials against Citizens of Ukraine in the Russian Federation.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 8, no. 1 (May 11, 2016): 155–81. doi:10.1007/s40803-016-0026-x. (Online at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40803- 016-0026-x?wt_mc=Internal.Event.1.SEM.ArticleAuthorOnlineFirst).

* * *

This article has been prepared with the support of the European Union in Ukraine. The content of the article is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the position of the EU

This article has been prepared with the support of the European Union in Ukraine. The content of the article is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the position of the EU